INTRODUCTION

Among recent protestant scholars, there have been some quite significant refinements in the Trinitarian thought. Wolfhart Pannenberg stands out as perhaps one of the most important contributors to the protestant theology of Trinity in the mid-twentieth century. This piece seeks to discuss Wolfhart Pannenberg and his contribution to the study of Trinity, and how he is distinct from Karl Bart who is seen as the most important contributor to the protestant theology of Trinity.

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE WRITINGS OF WOLFHART PANNENBERG ON THE TRINITY

Wolfhart Pannenberg was born in 1928 in the city of Stettin (today part of Poland). Growing up during the Nazi era, he was pressed into military service during the final days of the Third Reich – an experience which helps account for his wariness of all ideological and political promises. His interest in religion developed after the war as the result of study and reflection during his university days, first at Berlin, then at Gottingen, Basel, and Heidelberg, where he received his doctorate in 1953; writing on the idea of predestination in the thought of Duns Scotus. In 1958, he was appointed professor of systematic theology at Wuppertal, a theological seminary of the Confessing Church. Important university positions followed, first at Mainz (1961) and then at Munich (1968) (Encyclopedia web).

In the earlier writings of Wolfhart Pannenberg, they were no much reference to the doctrine of the Trinity. However, a 1981 study revealed a change of heart for Pannenberg who claimed that God was initially unknown to him not until he it was made closer to him by God through Jesus Christ (Pannenberg 263).

WOLFHART PANNENBERG THOUGHT ON THE TRINITY

“In the first volume of his Systematic Theology in 1991, Pannenberg presents his mature thought on the subject of the Trinity. “He identifies as the very heart of Jesus’ message the announcement of the proximity of the divine reign” (LaDue 131). For Pannenberg, it is in Christ that God manifests himself definitively as Father. The Old Testament only infrequently refers to the God of Israel as Father. In 2 Samuel 7:14 God declares himself to be the Father of David, the king of Israel. Much later in Isaiah 63:16, common prayer is directed to God as Father because the whole people are then seen as sons and daughters of God. For Jesus, “Father” is the proper name for God. He clearly differentiates himself from the Father, whom he identifies as greater than himself (John 14:28). This differentiation is likewise reflected in the Lord’s Prayer. Paul declares that by Jesus’ resurrection from the dead he was confirmed the divine Son (Rom 1:3-4) whose full stature will be disclosed only in the last days. For Pannenberg it was a short distance from this communication between point to the affirmation of his preexistence (Gal 4:4). The term Kurios – proper name for God – was predicated of the risen Christ and carries the notion of his full deity (John 20:28).

THE PLACE OF THE HOLY SPIRIT IN THE TRINITY FOR WOLFHART PANNENBERG

For Pannenberg, “the Holy Spirit is seen as the genus and the Father and the agent who shares the life of the exalted Christ with believers (Rom 8:11). By receiving the Spirit, believers share in the divine sonship of Jesus” (LaDue 132). According to Pannenberg, “the fellowship of Jesus with the Father implies the person of the Spirit in the relationship. In fact, the Spirit is the medium of God’s presence in Jesus, much as the Deity was present through the Spirit in the Old Testament prophets. The involvement of the Holy Spirit in the work of Christ and in the union between Jesus and the Father indicates that the Christian understanding of God reached its mature configuration in the doctrine of the Trinity” (Systematic Theology, 268). The very early appearance of the baptismal formula (Matt 28:19) contributed significantly to the theology of the Trinity, particularly in the Western church.

NEW TESTAMENT ON THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE TRINITY IN WOLFHART PANNENBERG THOUGHT

Although the New Testament statements do not clarify the relationships among the three divine figures, they do attest to the fact that they are interrelated. Paul distinguishes between the pneuma and the kurios but not as clearly as does John, who identifies the Holy Spirit as another Advocate (John 14:16). The second Advocate who will come when Jesus leaves (John 16:7) is truly distinct from the Son. This distinction between Christ and the Spirit was not clearly seen by all the Fathers in the second and third centuries (e.g., Irenaeus), but in Tertullian and Origen the Son was portrayed as distinct from both the Father and the Holy Spirit. This is what grounded the notion that there are three persons in the Trinity. The challenge, of course, was to reconcile this notion with the heavy monotheistic emphasis in the traditional biblical portrait of God. The Monarchians protested against the three-fold divine persons, while the subordinationists affirmed the essential supremacy of the Father. It was largely Athanasius (ca. 295-373) who dealt the fatal blow to subordinationism prior to the Council of Constantinople I (381), which professed the full divinity of both the Son and the Spirit. The Cappadocians taught that the unity of the three divine persons is rooted in their common activity, but the divine activity did not provide any real foundation for a distinction of persons (Pannenberg, Systematic theology, 278).

CHURCH FATHER’S VIEW ON THE TRINITY ACCORDING TO WOLFHART PANNENBERG ANALYSIS

The Cappadocians also emphasized that the Father is the source of the Deity, such that the Divine Being was understood as proper to the Father alone, with the Son and the Spirit viewed as the recipients of the divinity from the Father. In the age of high scholasticism, the existence, nature, and attributes of God were consistently addressed before the consideration of the three divine persons. Anselm (1033-1109) was convinced that he could deduce the Trinity from the divine unity by distinguishing the thinker, the thought, and the love that connects them in the one essence. Richard of St. Victor (d. 1173), by focusing on God as love, insisted that this calls forth a plurality of persons, for God’s love requires a fully divine person as a suitable beloved. Further, the love of Father and Son is totally expressed in the Holy Spirit, for those joined together in love should have a third to share it (287). Thomas Aquinas (1225-74) adopted Augustine’s approach and refined it. For the bishop of Hippo, the distinctions conditioned by their mutual relations, which among the persons are in the divine essence are not mutable, nor are they accidents. For Aquinas, the intra-divine processions establish the doctrine of the persons as subsistent relations. “Pannenberg affirms that Aquinas more than anyone else formulated the classical doctrine of the Trinity” (LaDue 133).

THE REFORMERS ON THE TRINITY IN PANNENBERG THOUGHT AND HIS CRITIQUE OF KARL BARTH

The Reformers also treated the existence and nature of God before considering the Trinity. They insisted on the development of the doctrine from scriptural sources. By the nineteenth century, according to Pannenberg, “Protestant thinkers felt the need to reestablish belief in the concept of Spirit. In the philosophy of G.W. F. Hegel (1770-1831), the doctrine of the triune God in terms of the self-conscious Spirit achieved its classical form” (292). He arrived at a plurality of persons through the notion of love but was unable to reconcile this with his idea of the self-consciousness of the absolute Spirit. “Karl Barth placed the immanent Trinity as the centerpiece of his systematics, but for him there is no plurality of persons, but rather three distinct modes of being in the one divine subjectivity. In Pannenberg's judgment, the notion of love allows for a distinction among the divine persons more readily than the concept of spirit. There remains, however, the danger that the equal status of the Son and the Holy Spirit with the Father is compromised to the extent that God is first and foremost identified as Father. The most effective way to approach the doctrine of the Trinity is to reflect on how the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit manifest themselves and relate to one another in history” (LaDue 133).

Pannenberg argues that it is difficult to find clear Trinitarian statements in the New Testament. Even the baptismal formula in Matthew 28:19 fails to provide an adequate base for Trinitarian theology because it does not answer the question concerning the relations among the persons (Pannenberg, Systematic Theology, 301). The New Testament affirms the divinity of the Son (eg. John 20:28) and of the Spirit (John 15:26; 1 Cor 2:10), but the trinitarian formulas do not clearly disclose the triune pattern of the Divinity. It is critical that we begin with the relationship between Jesus and the Father Christ as recalling that the New Testament declarations identify divine Son. The Holy Spirit is seen as a distinct figure as we come to understand Jesus as the preexistent Son and begin to appreciate the Spirit’s separate and indispensable role in salvation history.

Jesus distinguishes himself from the Father (John 14:28), and in the act of self-distinction he identifies himself as God the Son. Christ is seen as the one who fulfills the role assigned to him by the Father. This sharing of power between Father and Son reveals the radical relationship between the two. In this transfer of power, the Father’s kingdom and his divinity are made dependent on the Son. In the passion and death of Jesus, the Father also is deeply affected, for he is identified as love. The distinction of the Holy Spirit from the Father and Son is dramatically disclosed in John 14:16. Pannenberg observes that “the Church Fathers used this as a basis for their observations concerning the Spirit as a distinct person. As the Son glorifies the Father (John 17:4), so the Spirit will glorify the Son (John 16:14)” (315). John’s declarations concerning the coming of the Paraclete (e.g., 15:26) provide the rationale for the Spirit’s role in carrying forward the mission of Christ.

CRITIQUE OF SAINT AUGUSTINE

“Pannenberg attests that we cannot hold with Augustine that the Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son” (LaDue 134). He teaches that “the Spirit proceeds from the Father and is received by the Son. The Son shares with the Father in the sending of the Spirit into the world. Because of this, the Spirit can rightly be called the Spirit of Christ. But this does not alter the fact that the Spirit originates and proceeds from the Father” (Systematic theology, 317). “Pannenberg recommends, therefore, that the filioque in the creed of Constantinople I be eliminated because it does not reflect the teaching of the New Testament and is a Western addition that has never been agreed to by the East” (LaDue 134).

PANNENBERG AND KARL RAHNER ON THE MODE OF THE TRINITY

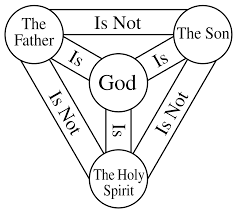

“For Pannenberg the divine persons are not three modes of being in the one divine subject. They are rather three separate and dynamic centers of action. They can be considered three separate centers of consciousness, whereas Karl Rahner insists that the one divine consciousness exists in a threefold mode. Pannenberg asserts that the divine subsistent relations are not merely the result of their differences of origin. In addition to generating the Son, the Father has handed over his kingdom to him and will receive it back from him in the final days. The Son is not just begotten of the Father, he is also lovingly obedient to him throughout his life on earth. Thus, he glorifies the Father as the ever-faithful Son. Similarly, the Holy Spirit is not just spirated. He fills the Son and glorifies him. Each of the divine persons is related in many ways to the other two. The trinitarian relations of origin do not express the full range of the intricate relatedness among the three” (LaDue 134-5).

The view of the Cappadocians that the Father is the font and the three source of the Deity actually seems to threaten the equality of the three. The Son is equal to the Father ontologically, but he subjects himself to the Father as the divine Son, as well as in the fulfillment of his mission. As Pannenberg says, “The unity of the trinitarian God cannot be seen in detachment from his revelation and his related work in the economy of salvation” (systematic theology 327). The monarchy of the Father is realized through the work of the Son and the Holy Spirit, who are the divine agents in creation and in salvation history. Thus, the Father makes dependent on the actions of the Son and the Spirit in history. The divine persons dependence on one another is reflected in the crucifixion, when even the deity of the Father can be questioned. The personal subjectivity of the Holy Spirit is confirmed and expressed in the glorification of the Father and the Son.

PANNENBERG IDEOLOGY ON THE FULL REVELATION OF GOD

“Pannenberg stresses that the full revelation of the triune God will be completed only in the eschaton. He affirms that the divine unity cannot be adequately addressed until we have set forth our best faith understanding of the triune persons. This approach reverses the treatment of the Deity that, from the Middle Ages, began with the nature and attributes of the one God and then concentrated on the Trinity of persons. Pannenberg insists that the divine persons are separate centers of action, rather than mere modes of being of the one divine subject. However, they are never to be considered as three species of a common genus, namely God. The Church Fathers from the earliest days insisted that we can know the existence of the Deity, even though the divine essence is beyond our grasp. Aquinas taught that God’s perfection, goodness, infinity, and eternity could be deduced from the idea that he is the first cause of all things. Luther affirmed that we have an intuitive knowledge of God’s existence, although God’s identity and nature remain veiled in mystery. According to Pannenberg, it is imperative that we conceive of the Deity as an active and abiding presence in the world, rather than a merely transcendent reality” (LaDue 135). “The essence of the one God is revealed by both Father and Son and by their communion in a third, the Spirit, who proceeds from the Father and is received by the Son and given to his people” (Pannenberg 258-9). The three persons that constitute a single constellation.

The qualities that we predicate of God reflect his relations to creation. His infinity and eternity remove spatial and temporal limits, while omniscience, omnipotence, and omnipresence are his positive qualities. Since there is no composition in the Deity, the Triunity of God can be known to us only through supernatural faith. Hegel felt that God can be known to us only through that of the concept of science were defined in a more relational manner, this would make the three subsistent relations in the Trinity somewhat more credible to us. In Pannenberg’s view, “the trinitarian figures can be distinctively described as persons on the basis of their unique self-relations that are mediated through their relationships with each other” (384). He reiterates that the essence of the Deity is not to be considered a separate subject in addition to the three persons, who cannot simply be reduced to aspects of the one divine subject. Rather, the three persons and they alone are the immediate subjects of the divine activity. The Deity as such is not to be conceived as an agent distinct from the activity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The early Christians understood that the final events of salvation history would be made known only in the last days when the saving plan of the Father, Son, and Spirit will be fully revealed. Although the Deity is not in any way completed by the divine activity in the world, God does become dependent on the fulfillment of his salvific plan in history. The statement in John that “God is Spirit” (4:24) provides a reflection of the divine essence, as does another observation in John that “God is Love” (1 John 4:18). All the other attributes of the Deity flow out of the notions of divine infinity, God as Spirit, and God as Love (LaDue 136).

PANNENBERG ON THE DIVINE ATTRIBUTE

Pannenberg then proceeds to analyze the more significance of the divine attributes. “Infinity, for example, is implied in a good number of the biblical descriptions of God and is related to the divine holiness. Separation from everything profane or secular is the definition of holiness, which implies the need to protect worship from defilement. By the same token, the profane world must be protected from the holy, for contact with the holy can on occasion cause death (Exod. 19:12). The holiness of God is expressed first and foremost in his acts of judgment. The divine eternity stands in stark contrast to the frailty and corruptibility of all creation, and this leads to the notion that God is open to all reality-the past, the present, and the future. The divine omnipotence can be considered as a consequence of his eternity. Because all things are present to him, he has power over all of reality” (Pannenberg 415).

Both John (3:16) and Paul (Rom 5:5) declare that the most important message revealed throughout the life of Jesus is that in him God’s love is manifested in a unique and privileged manner in the world. From the history of Jesus, we discover that the three divine figures have their personal distinctiveness through their mutual relations. The Father is Father only in relation to the Son, and the Son is Son in perfect obedience to the Father. The Spirit is Spirit as he glorifies the Father and the Son and unites them. Each divine figure is distinct in the working out of his personal existence (428).

CONCLUSION

Pannenberg suggests that we can envision the trinitarian life as a progressive revelation and unfolding of the divine love. The manifold functions of the divine persons in the cosmos and in human history are further enunciated in dogmatic theology through the treatment of creation, reconciliation, and redemption. Only with the consummation of the world does the doctrine of God reach its final phase. At the end of history, the unique characteristics of the three divine persons will be revealed more clearly.