It's a sunless Sunday in La Paternal and in that brief geographical continuity called Villa General Mitre. The two young men who are walking next to Juan Agustín García say it with an inherited pride: "Let's go to Maradona."

They did not see the founding Diego, but they were told the details of that legend that inhabits every corner they now visit. The greatest star was beginning to grow in this geography, sheltered from so many cold mornings on the same stage that now pays tribute to him.

The two children, like so many other children, go to see an Argentinos that plays little or not at all as in the days of El Diez. But they feel that it is theirs, that it belongs to them, that it is among all those who in some way go to Boyacá, even though it resides in far-off Dubai.

The scene is not a coincidence: Diego made Argentinos Argentinos. For what he offered - those 116 goals in 166 games that made him the top scorer in the history of the club - and for what he generated. From his millionaire transfer, another team of magicians soon emerged that produced the best cycle in the history of the club, that of the first titles, that of the Libertadores, that of Bichi Borghi, that of Castro and Ereros, that of Olguín and Panza Videla. Since his time in La Paternal, the world knew that the best breeding ground was in that corner of Buenos Aires. Just that. Everything that.

It was a phenomenon with unique characteristics. The journalist Miguel Ángel Vicente tells us about it in his book Mitos y pensamientos del fútbol argentino: "Word had spread in those days. It was said, and rightly so, that Argentinos Juniors was like the best champagne. For a few. It was almost forbidden for general consumption, because the team from La Paternal, despite its renowned style of play, had very few clients, few followers, few fans compared to the big teams, but Diego Armando Maradona arrived and the story became popular.

Fans appeared in all the stands and all they went to see was the magic of the genius. Of the kid who left his mark on the day of his debut against Talleres de Córdoba, at 16 years old, when he showed all his irreverence by giving Juan Domingo Cabrera a nutmeg. Those fans were from other teams. It was easy to identify them, always sitting on the sides of the stands, dispassionate about the shirt, delighted with the football that Diego gave them. It was an idyll that began in 1976 and continued forever. Although in 1981 he was already playing for Boca, his mark is still present in La Paternal.

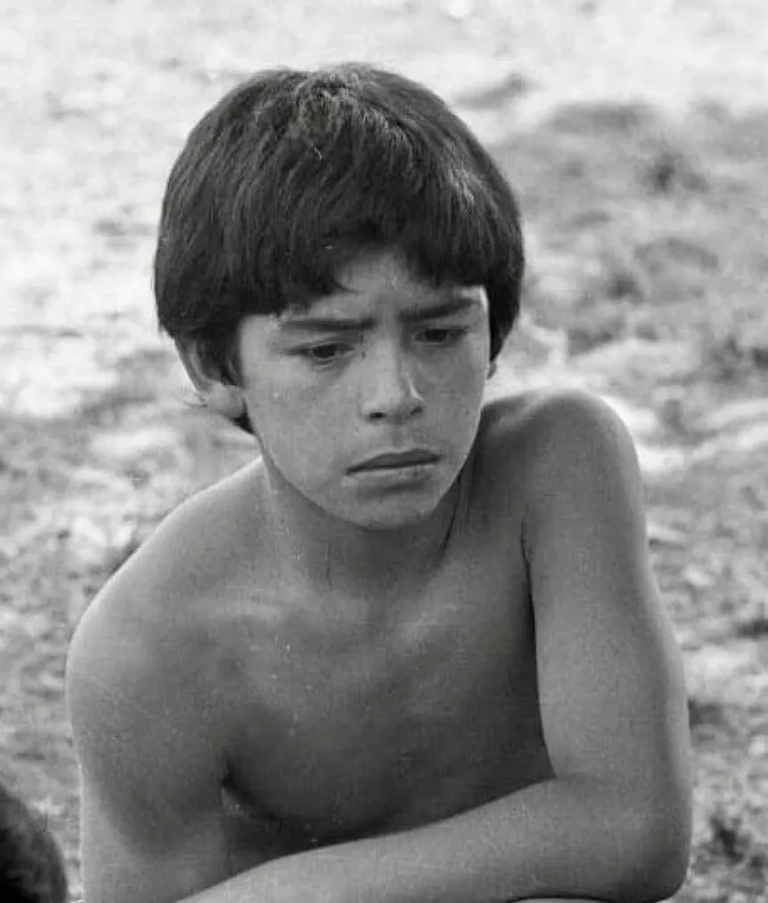

On October 20, 1976, the official story began. It was a different Diego. It couldn't have been any other way. Miguel Angel Bertolotto, who covered the opening game against Talleres de Córdoba for the newspaper Clarín, portrayed him - in some corner of this Editorial Office -: "He looked like a wet little chicken sitting there, on the rustic wooden bench in the farthest and darkest corner of the old dressing room."

The youthful face, the lively eyes full of wonder, the head full of black curls, the voice almost inaudible. Little by little he was surrounded by journalists, inaugurating what would be a constant in his life as a novelist. Eight, ten, twelve reporters caught by curiosity: a boy of barely 15 years old was already in the First Division. 'In ten days, on the 30th, I'll be 16...', he introduced himself. And other phrases had to be extracted from him with a corkscrew. Questions of time: the mute child later became the man of the most universal verbosity.

Javier Roimiser is a doctor, but above all else there is another passion that drives him: his name is Argentinos. He was born in October 1974 and his childhood found him watching Maradona on black and white television. While his friends followed various imported superheroes, he chose to watch Diego. He could not change. He confesses it now and has always confessed it: he is a fan of Argentinos because of Maradona. Dedicating himself to medicine did not inhibit him: he is also a journalist and historian of the La Paternal club. He knows the details of that trip like no other.

And he tells, for example, that in the Ducó against Huracán, Maradona scored a goal as beautiful or even more beautiful than the one against the English in Mexico 1986. Goal after goal. Carlos Milani - central scorer in that Argentinos of 1977 - once told Roimiser: "The ball went from the defense to the back of Huracán's goal... they didn't touch it, it was Diego's greatest goal... I was holding my head." and I couldn't believe it... as an anecdote, the whole stadium applauded for three or four minutes and Nitti didn't give the order to leave the center of the field looking at Diego... If Negro Enrique boasts of having given Maradona the pass-goal against the English, I gave Diego the most beautiful pass-goal he made. I took the goal kick and gave it to his foot in the midfield of our area." At the Veterans' Association of Huracán, they express themselves with a rare boast: "The best Maradona passed through here, through the Palace." Magic of football. And of Diego.

In the story of the star and the club that gave him the world, there were anecdotes that make you want to hug them every day. His absurd exclusion from the National Team's squad for the 1978 World Cup is unavoidable. Diego was angry. He had missed seven games at the Metropolitano due to his concentration. He returned on May 21 against Chacarita and scored three goals. From that game came a phrase that walked the streets of the City with an air of fame: "Maradona should not be disqualified from anywhere else because he gets angry and scores three goals." With Messi, now, something similar happens: every time someone bothers him, the star from Rosario resolves the differences with goals.

Episodes from that spell emerge in various memories. From their own and from others. From lifelong supporters and occasional supporters. In 1980, under Diego's orders, Argentinos was having one of the best seasons in its history, along with 1960 and 1926. On the 18th matchday of the season, they visited the leader River. After fifteen minutes, at the Monumental, referee Alberto Ducatelli awarded a penalty to Argentinos. Ubaldo Fillol, a sporting hero of the time, met Maradona from the National Team. And he said to him in a low voice: "Now I'll save it for you." And so he did. El Pato flew and saved. Faced with the goalkeeper's smile, the rising El Diez did not hold back and made a promise, with the anger of a wounded lion: "You'll see, now I'm going to score two goals..." And then, Diego was Maradona and Argentinos won 2-0. With his two goals, of course.

Something similar happened to the other great goalkeeper of the time. Hugo Gatti, from Boca, told him he was a chubby boy. Diego from Argentinos responded with four shouts that lasted forever. Just like his record: for five consecutive tournaments (between 1978 and 1980) he was the top scorer. He could not do the victory lap that he so desired and that he would do in his next stint at Boca (in 1981). But he achieved something even greater: he put the club from La Paternal on the map of universal football. And those who saw it and enjoyed it - his own, others, the impartial, everyone - now feel the pleasure of telling it with pride: "I saw Diego play for Argentinos," they say, repeat, rejoice. They feel it as if it were a personal discovery. But, perhaps, they are wrong: Diego, from Argentinos, was, is and will be for everyone. Or at least that is what it seems. Or at least that is what it seems.

I hope you enjoyed this post. If you have any questions, queries or would like to add to this post, please feel free to write in the comments section.

Es un domingo sin sol en La Paternal y en esa breve continuidad geográfica llamada Villa General Mitre. Los dos jóvenes que pasean junto a Juan Agustín García lo dicen con un orgullo heredado: "Vamos a Maradona".

No vieron a ese Diego fundacional, pero les contaron los detalles de esa leyenda que habita cada rincón que ahora recorren. El mayor crack comenzaba a crecer en esta geografía, cobijado de tantas mañanas frías en el mismo escenario que ahora le rinde homenaje.

Los dos niños, como tantos otros niños, van a ver a un Argentinos que juega poco o nada como en los días de El Diez. Pero sienten que es de ellos, que les pertenece, que está entre todos los que de alguna manera van a Boyacá, aunque resida en la lejana Dubái.

La escena no es casual: Diego hizo Argentinos Argentinos. Por lo que ofreció -esos 116 goles en 166 partidos que le hicieron y le convierten en el máximo goleador de la historia del club- y por lo que generó. De su millonario traspaso, pronto surgió otro equipo de magos que produjo el mejor ciclo de la historia del club, el de los primeros títulos, el de la Libertadores, el de Bichi Borghi, el de Castro y Ereros, el de Olguín y Panza Videla. Desde su paso por La Paternal, el mundo sabía que el mejor caldo de cultivo estaba en esa esquina de Buenos Aires. Solo eso. Todo lo que.

Fue un fenómeno con particularidades únicas. Lo cuenta el periodista Miguel Ángel Vicente, en el libro Mitos y creencias del fútbol argentino: "Se había corrido la voz en esos tiempos. Se decía, y con razón, que Argentinos Juniors era como el mejor champagne. Para unos pocos. Era casi prohibido al consumo general, porque el equipo de La Paternal, a pesar de su reconocida línea de juego, tenía muy poca clientela, pocos seguidores, poca afición en comparación con los grandes equipos, pero llegó Diego Armando Maradona y la historia se hizo popular.

Aparecieron aficionados en todas las gradas y lo único que fueron a ver fue la magia del genio. Del pibe que puso su sello el mismo día de su debut ante Talleres de Córdoba, a los 16 años, cuando mostró toda su irreverencia tirándole un caño a Juan Domingo Cabrera. Esos aficionados eran de otros equipos. Era fácil identificarlos, siempre sentados a los costados de la grada, desapasionados con la camiseta, encantados con el fútbol que les regalaba Diego. Fue un idilio que comenzó en 1976 y continuó para siempre. Aunque en 1981 ya jugaba en Boca, su huella sigue presente en La Paternal.

El 20 de octubre de 1976 comenzó la historia oficial. Era otro Diego. No podría ser de otra manera. Miguel Angel Bertolotto, quien cubrió para el diario Clarín aquel partido inaugural ante Talleres de Córdoba, lo retrató -en algún rincón de esta Redacción-: "Parecía un pollito mojado sentado ahí, en la rústica banca de madera en el fondo más lejano y oscuro". rincón del antiguo vestidor.

El rostro juvenil, los ojos vivos llenos de asombro, la cabeza llena de rizos negros, la voz casi inaudible. Poco a poco se fue rodeando de periodistas, inaugurando lo que sería una constante en su vida de novelista. Ocho, diez, doce reporteros atrapados por la curiosidad: un muchachito de apenas 15 años ya estaba en Primera División. En diez días, el 30, cumplo 16...', se presentó. Y había que sacarle otras frases con un sacacorchos.” Cuestiones de tiempo: el niño mudo se convirtió luego en el hombre de la verborrea más universal.

Javier Roimiser es médico, pero por encima de todas las cosas hay otra pasión que lo impulsa: su nombre es Argentinos. Nació en octubre de 1974 y su infancia lo encontró viendo a Maradona en la televisión en blanco y negro. Mientras sus compañeros seguían a varios superhéroes importados, él optó por observar a Diego. Ya no podía cambiar. Lo confiesa ahora y lo ha confesado siempre: es hincha de Argentinos por Maradona. Dedicarse a la medicina no lo inhibió: también es periodista e historiador del club de La Paternal. Conoce los detalles de ese viaje como ningún otro.

Y cuenta, por ejemplo, que en el Ducó contra el Huracán, Maradona marcó un gol tan bonito o incluso más bonito que el de los ingleses en México 1986. De gol en gol. Carlos Milani -goleador central en aquel Argentinos de 1977- le dijo una vez a Roimiser: "El balón se fue de la defensa al fondo de la portería de Huracán... no la tocaron, fue el gol más grande de Diego... Me estaba agarrando la cabeza". y no lo podía creer... como anécdota, todo el estadio aplaudió durante tres o cuatro minutos y Nitti no dio la orden de salir del centro del campo mirando a Diego... Si el Negro Enrique se jacta de haberle dado a Maradona el pase-gol contra los ingleses, le di a Diego el pase-gol más bonito que hizo. Cogí el saque de meta y se lo di al pie en el mediocampo de nuestra área”. En la Mutual de Veteranos de Huracán, se expresan con un raro alarde: "El mejor Maradona pasó por aquí, por el Palacio". Magia del fútbol. Y de Diego.

En esa historia del crack y el club que le dio el mundo, hubo anécdotas que dan ganas de abrazar todos los días. Su absurda exclusión de la convocatoria de la Selección para el Mundial de 1978 es ineludible. Diego estaba enojado. Se había perdido siete partidos del Metropolitano por su concentración. Regresó el 21 de mayo ante Chacarita y marcó tres goles. De ese partido nació una frase que caminó con aires de fama por las calles de la Ciudad: "Maradona no debe ser descalificado de ningún otro lado porque se enoja y mete tres goles". Con Messi, ahora, pasa algo parecido: cada vez que alguien le molesta, el crack rosarino resuelve las diferencias con goles.

Los episodios de ese hechizo brotan en diversas memorias. De los propios y de los demás. De simpatizantes de toda la vida y simpatizantes ocasionales. En 1980, a las órdenes de Diego, Argentinos estaba teniendo una de las mejores temporadas de su historia, junto con 1960 y 1926. En la jornada 18 de la temporada, visitaba al líder River. Al cuarto de hora, en el Monumental, el árbitro Alberto Ducatelli señaló penalti a Argentinos. Ubaldo Fillol, héroe deportivo de la época, conoció a Maradona de la Selección. Y le dijo en voz baja: "Ahora te lo guardo". Y así lo hizo. El Pato voló y atajó. Ante la sonrisa del portero, el ascendente El Diez no se inhibió e hizo una promesa, con la ira de un león herido: "Ya verás, ahora voy a meter dos goles...". Y luego, Diego fue Maradona y Argentinos ganó 2-0. Con sus dos goles, claro.

Algo similar le sucedió al otro gran portero de la época. Hugo Gatti, de Boca, le dijo que era un gordito. Diego de Argentinos respondió con cuatro gritos que duraron para siempre. Al igual que su récord: durante cinco torneos consecutivos (entre 1978 y 1980) fue el máximo goleador. No pudo dar la vuelta olímpica que tanto deseaba y que haría en su siguiente paso por Boca (ya en 1981). Pero logró algo aún mayor: puso al club de La Paternal en el mapa del fútbol universal. Y quienes lo vieron y disfrutaron -los suyos, los demás, los imparciales, todos- ahora sienten el placer de contarlo con orgullo: "Vi a Diego jugar para Argentinos", dicen, repiten, se regocijan. Lo sienten como si fuera un descubrimiento personal. Pero, quizás, se equivoquen: Diego, de Argentinos, fue, es y será de todos. O al menos eso es lo que parece. O al menos eso parece.

Source images / Fuenbte imágenes: Argentinos Junios.

Espero que esta publicación te haya gustado. Si tienes alguna duda, consulta o quieras complementar este post, no dudes en escribir en la zona de comentarios.

Sources consulted (my property) for the preparation of this article. Some paragraphs may be reproduced textually.

Fuentes consultadas (de mi propiedad) para la elaboración del presente artículo. Algunos párrafos pueden estar reproducidos textualmente.

| Argentina Discovery. |  |

|---|---|

| Galería Fotográfica de Argentina. |  |

| Viaggio in Argentina. |  |