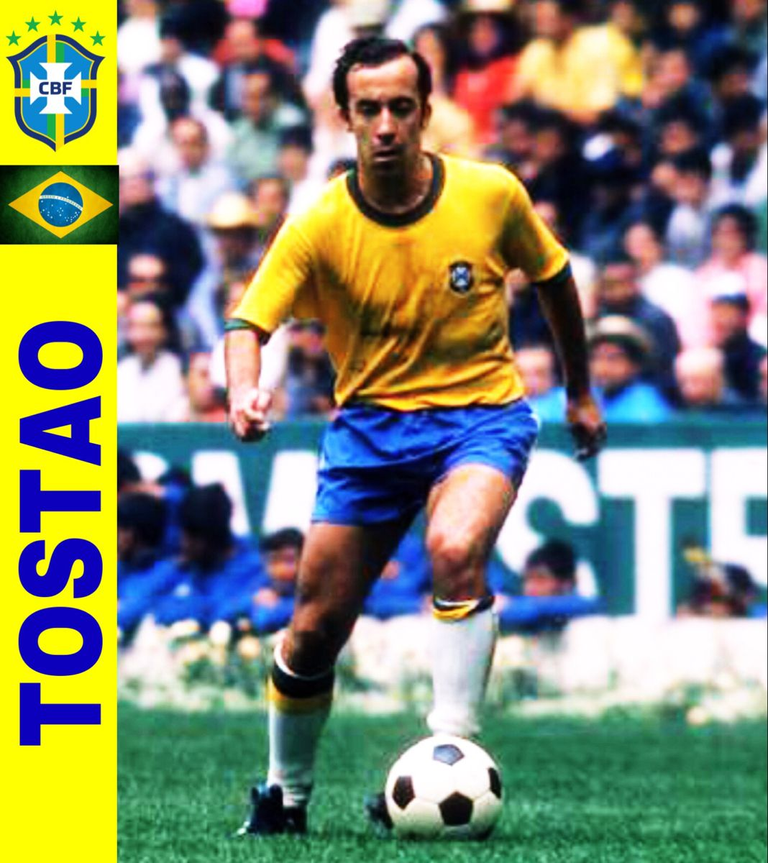

The Brazilian, who retired at just 26, was one of the great stars of the 1960s and 1970s. He stood out at the World Cup in Mexico, as a perfect partner for Pelé.

Off the field, he challenged dictatorships and helped the unprotected. On it, he shone.

The World Cup's heartbeat is already being felt in this prelude that is coming to an end. It happens in every city that shows itself to the world as the host of the great event and in every corner of the immense Brazil. Now, even beyond the social protests over the organization's wastefulness. Anxiety is growing or being concealed by the omnipresent ghosts of the old Maracanazo or by the happy memories of so much embraced glory.

The pessimists feared that 2014 would shelter a new Obdulio Varela or allow a devastating goal like Alcides Ghiggia 's . The optimists were excited imagining the repetition of a jump like Pelé's in the final against Italy or some goal of the many that Ronaldo - the original, the most talented fat man in history - offered to the World Cup. There are also those who aspire to beauty: they trust that this edition can offer the charms of a Tostão.

His stature is revealed by one detail: FIFA chose him among the 20 best South American footballers of the 20th century. And in that same ranking he appeared in the top 5 among Brazilians, together with Pelé, Garrincha, Zico and Zizinho. A little less than two decades ago, Tostão - now a doctor, now a commentator - told himself in his autobiography Tostão: Lembranças, Opinions and Reflections on Football: "I stood out for my passes, my short dribbles, my arrival into the area to score and, mainly, my ability to anticipate plays.

But I had several defects that diminished over time, thanks to many daily training sessions: I almost only kicked with my left leg, I headed badly, with my eyes closed, I was slow in medium and long spaces, I didn't have a good shot from outside the area. My technique, my athleticism and my speed couldn't keep up with my thoughts. However, I practiced a lot of self-criticism: I always thought I could play better." From his ability to observe himself came the transformation: defects became virtue. And then delight. He achieved it with a relentless formula: he added constant work to natural talent.

The journalist Manolo Eppelbaum, who knows a lot about Brazilian football and knows a lot about Tostão, tells Clarín from Rio de Janeiro: "Tostão was the vindication of true football-art in the highest degree. And no wonder. Since, at the end of the sixties, the so-called 'Football-Strength' was leaving its mark, with rare exceptions. And it did not only influence Brazil since that style was wonderfully captured by Holland as well. And even by Spain in more recent days." In short, Tostão was the emblem and a perfect representative of a way of understanding football. He, who could be a midfielder or forward with equal ease, offered himself as a mirror of a universal patent: the jogo bonito.

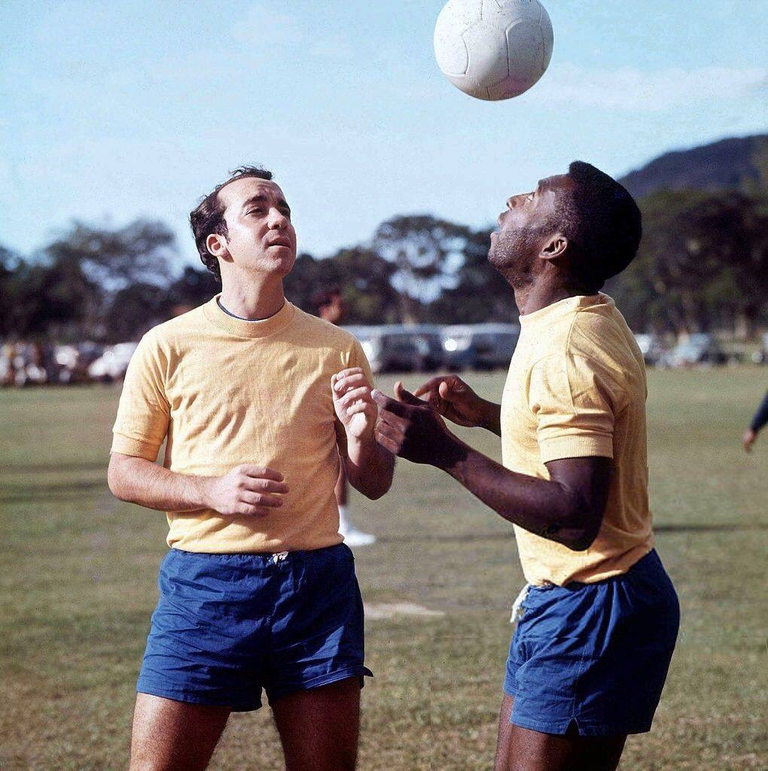

In reality, Tostão was born in Belo Horizonte, in 1947, with a much longer name that the memory of football does not register as his own: Eduardo Gonçalves de Andrade. The nickname has a curious history: it refers to the old Brazilian 10-cent coin. The reason: the star used to be the smallest in the teams he played for. Like the small coin. But his football was capable of denying ages and sizes: at 23 years old, in the World Cup in Mexico, he became a universal and forever star. He offered the world his talent, his brilliance, his skill. He was, in that Brazil of 1970 -paradigm of great football- the ideal partner of Pelé. His participation in that World Cup was pure magic.

He played six games, scored four goals, heard thousands and thousands of applause. Eduardo Galeano once recalled three iconic images from that most important event: "The image of Beckenbauer, with one arm tied, fighting until the last minute; the fervour of Tostão, who had just had an eye operation and stood firm in all the matches; the flightiness of Pelé in his last World Cup: 'We jumped together', said Burgnich, the Italian defender who marked him, 'but when I came back to earth, I saw that Pelé was still suspended in the air'". The pedestal of the -perhaps- best team of all time had Tostão among its inhabitants. But he did not only stand out in the green and yellow team. He is also one of the greatest historical representatives of Cruzeiro and Belo Horizonte football. With the blue team he won the historic Penta at the Estadual Mineiro between 1965 and 1969. During that same period, in 1966, he also won the Copa de Brasil, in which he became a true superhero. He was the star of the two finals against Santos. He appeared on the front pages of the newspapers. The huge headlines said he was the new king of football. The white Pelé. He later said that he was ashamed of all the praise.

João Máximo, a journalist from the newspaper O Globo, recently defined him precisely in a handful of words: "The shy man from Minas Gerais who enchanted the world." They said he spoke little. But at the same time he said a lot. The writer Antonio Falcao portrayed him from a year that was key in the formation of the footballer beyond the field of play, 1968. "That year - when the Brazilian military dictatorship exacerbated stupidity itself, when the students of France challenged De Gaulle and when the people of Prague wanted to democratize socialism - would mark the off-field crack.

He, with political conscience, was saddened to see his country frustrated by what he considered to be the political ideal and of greater dignity: freedom. Discreet, our young athlete sympathized with those who fought for a democratic state of law. Furthermore, taking advantage of his prestige, Tostão never refrained from expressing an opinion in favor of the forgotten of the country and against the systematic torture of political prisoners. Or on theses that were dear to him, and I believe still are, such as agrarian reform and the redistribution of wealth in Brazil." Tostão was -and is- great not only on that playing field where he shone...

A little more than two years after his peak and while he was beginning to offer football lessons in the Rio de Janeiro championship (in 1972 he moved from Cruzeiro to Vasco da Gama), Tostão made a decision: at the age of 26 he left football.

The reason was medical: an inflammation of the retina of the eye that had been operated on before the World Cup in Mexico. It was a kind of double paradox: it happened to him, who had offered beauty to the eyes of the world; it happened to him, who watched football better than almost everyone else.

He was advised not to continue playing. He accepted without trauma.

In February 1973 he played his last match against Argentinos Juniors. Two weeks earlier he had scored his last goal, against Flamengo. When the news of his farewell to football became known, the jogo bonito dressed in black for several days.

It was in mourning.

I hope you liked this post. If you have any questions, queries or would like to add to this post, please feel free to write in the comments section.

El brasileño, que se retiró con apenas 26 años, fue uno de los grandes cracks de los años 60 y 70. Se destacó en el Mundial de México, como perfecto socio de Pelé.

Fuera del campo de juego, ofrecía cuestionamientos a las dictaduras y ayuda a los desprotegidos. Adentro, resplandecía.

Los latidos del Mundial ya se perciben en esta antesala que se expira. Sucede en cada ciudad que se muestra al mundo como sede de la gran cita y en cada rincón del inmenso Brasil. Ahora, incluso más allá de las protestas sociales por despilfarros de la organización. La ansiedad se ensancha o se disimula con los fantasmas omnipresentes del viejo Maracanazo o con los recuerdos felices de tanta gloria abrazada.

Los pesimistas temìan que este 2014 cobijara a un nuevo Obdulio Varela o permitiera un gol devastador como el de Alcides Ghiggia. Los optimistas se entusiasmaban imaginando la reiteración de un salto como el de Pelé en la final ante Italia o algún gol de los tantos que Ronaldo -el original, el gordo más talentoso de la historia- le ofreció a la Copa del Mundo. También están los aspirantes a la belleza: ellos confían en que esta edición pueda brindar los encantos de un Tostão.

Su dimensión la cuenta un detalle: la FIFA lo eligió entre los mejores 20 futbolistas sudamericanos del Siglo XX. Y en ese mismo ranking aparecía en el top 5 entre los brasileños, junto a Pelé, Garrincha, Zico y Zizinho. Hace poco menos de dos décadas, Tostão -ya médico, ya comentarista- se contó a él mismo en su autobiografía Tostão: Lembranças, Opiniões e Reflexões sobre Futebol: "Me destacaba por los pases, las gambetas en corto, la llegada al área para marcar y, principalmente, mi capacidad de anticipar las jugadas.

Pero tenía varios defectos que fueron disminuyendo a lo largo del tiempo, gracias a muchos entrenamientos diarios: casi pateaba sólo con la pierna izquierda, cabeceaba mal, con los ojos cerrados, tenía poca velocidad en los espacios medios y largos, no tenía buen remate desde fuera del área. Mi técnica, mis condiciones atléticas y mi velocidad no conseguían seguir a mi pensamiento. Eso sí, practicaba mucho la autocrítica: siempre pensaba que podía jugar mejor". De su capacidad para observarse brotó la transformación: los defectos se hicieron virtud. Y luego deleite. Lo logró con una fórmula implacable: al talento natural le agregó trabajo constante.

El periodista Manolo Eppelbaum, quien mucho conoce el fútbol brasileño y mucho sabe sobre Tostão, le cuenta a Clarín desde Río de Janeiro: "Tostão fue la reivindicación del verdadero fútbol-arte en grado máximo. Y no es para menos. Ya que, a fines de la década del sesenta, dejaba huellas el denominado 'Fútbol-Fuerza', salvo raras excepciones. Y no solamente influyó en Brasil ya que ese estilo fue maravillosamente captado también por Holanda. Y hasta por España en días más recientes". En definitiva, Tostão fue el emblema y un perfecto representante de un modo de entender el fútbol. El, que podía ser mediocampista o delantero con idéntica facilidad, se ofrecía como espejo de una patente universal: el jogo bonito.

En realidad, Tostão nació en Belo Horizonte, en 1947, con un nombre bastante más largo que la memoria del fútbol no registra como propio: Eduardo Gonçalves de Andrade. El apodo tiene una historia curiosa: refiere a la antigua moneda brasileña de 10 centavos. La razón: el crack solía ser el más chiquito en los equipos en que jugaba. Como la pequeña moneda. Pero su fútbol era capaz de desmentir edades y tamaños: a los 23 años, en el Mundial de México, se convirtió en una estrella universal y para siempre. Le ofreció al mundo su talento, su brillo, su destreza. Fue, en aquel Brasil del 70 -paradigma de un fútbol estupendo- el socio ideal de Pelé.

Su participación en aquella Copa del Mundo fue pura magia. Jugó seis partidos, convirtió cuatro goles, escuchó miles y miles de aplausos. Eduardo Galeano, alguna vez, rescató tres imágenes icónicas de aquella máxima cita: "La estampa de Beckenbauer, con un brazo atado, batiéndose hasta el último minuto; el fervor de Tostão, recién operado de un ojo y aguantándose a pie firme todos los partidos; las volanderías de Pelé en su último Mundial: 'Saltamos juntos', contó Burgnich, el defensa italiano que lo marcaba, 'pero cuando volví a tierra, ví que Pelé se mantenía suspendido en la altura'". El pedestal del -quizá- mejor equipo de todos los tiempos lo tenía a Tostão entre sus habitantes.

Pero no sólo se destacó en el seleccionado verdeamarelo. Es también uno de los máximos referentes historicos del Cruzeiro y del fútbol de Belo Horizonte. Con el equipo azul obtuvo el histórico Penta en el Estadual Mineiro, entre 1965 y 1969. En ese recorrido, en 1966, también obtuvo la Copa de Brasil, en la que se convirtió en un auténtico superhéroe. Fue la figura de las dos finales ante el Santos. En la tapa de los diarios aparecía él. Los títulos enormes contaban que era el nuevo rey del fútbol. El Pelé blanco. Contó más tarde que tanto elogio le daba vergüenza.

João Máximo, periodista del diario O Globo, lo definió en días recientes con precisión en un puñado de palabras: "El mineiro tímido que encantó al mundo". Decían que hablaba poco. Pero al mismo tiempo decía mucho. El escritor Antonio Falcao lo retrató a partir de un año que resultó clave en la formación del futbolista más allá del campo de juego, 1968. "Ese año -en que la dictadura militar brasileña exacerbó hasta la propia estupidez, en que los estudiantes de Francia desafiaron a De Gaulle y en que el pueblo de Praga quiso democratizar el socialismo- marcaría el crack extra-campo.

Él, con conciencia política, se entristecía de ver su país frustrado de lo que él consideraba como ideal político y de mayor dignidad: la libertad. Discreto, nuestro joven atleta se solidarizaba con los que luchaban para un estado democrático de derecho. Además valiéndose de su prestigio, Tostão nunca se abstuvo de opinar en favor de los olvidados del País y contra la tortura sistemática de los presos políticos. O sobre tesis que le eran queridas, y creo que aún lo son, como la reforma agraria y la redistribución de la riqueza en Brasil". Tostão fue -y es- grande no sólo en ese campo de juego en el que resplandecía...

Poco más de dos años después de su máxima expresión y mientras comenzaba a ofrecer cátedras de fútbol en el campeonato carioca (en 1972 pasó del Cruzeiro al Vasco da Gama), Tostão tomó una decisión: a los 26 años dejó el fútbol.

El motivo era médico: una inflamación en la retina del ojo que le habían operado antes del Mundial de México. Era una suerte de doble paradoja: le sucedía justo a él, que ante los ojos del mundo había ofrecido bellezas; le sucedía justo a él, que miraba el fútbol mejor que casi todos.

Le aconsejaron que no siguiera jugando. Aceptó sin traumas.

En febrero de 1973 disputó su último partido ante Argentinos Juniors. Dos semanas antes había convertido su último gol, ante Flamengo. Cuando se conoció la noticia de su despedida del fútbol, el jogo bonito se vistió de negro por varios días.

Estaba de luto.

Espero que esta publicación te haya gustado. Si tienes alguna duda, consulta o quieras complementar este post, no dudes en escribir en la zona de comentarios.

Sources consulted (my property) for the preparation of this article. Some paragraphs may be reproduced textually.

Fuentes consultadas (de mi propiedad) para la elaboración del presente artículo. Algunos párrafos pueden estar reproducidos textualmente.

| Argentina Discovery. |  |

|---|---|

| Galería Fotográfica de Argentina. |  |

| Viaggio in Argentina. |  |

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks!