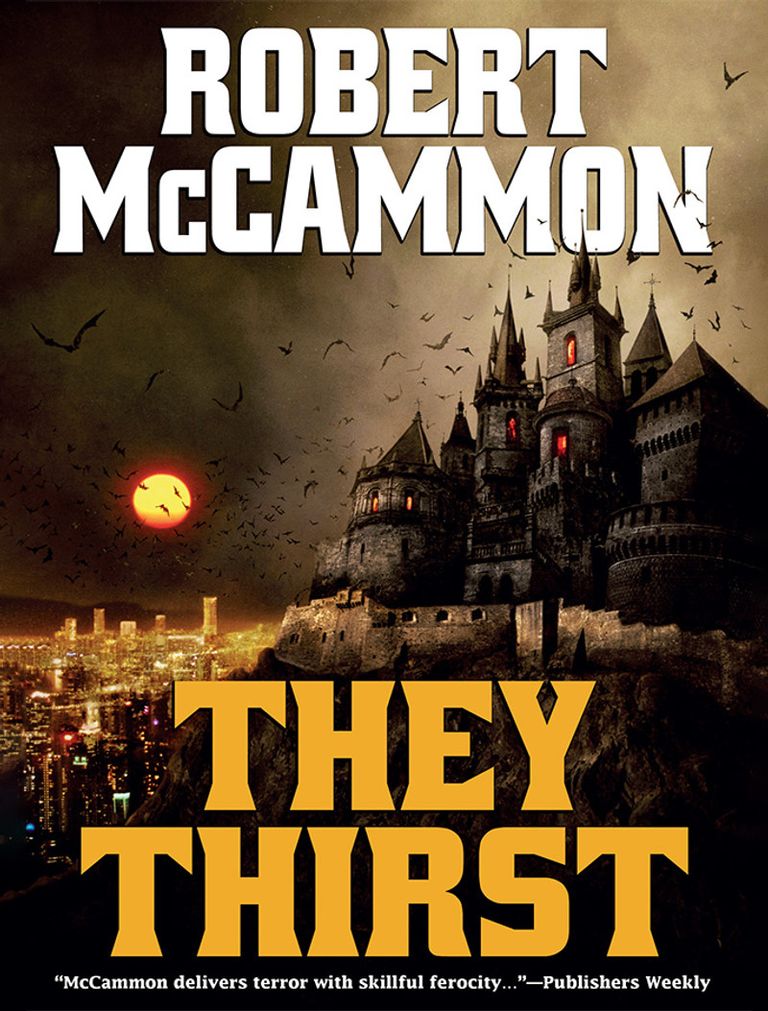

They Thirst is Robert McCammon's third book published in 1981.

An evil as old as the world has moved from the wastelands of an Eastern European country into the seething cauldron of the City of Angels, more than eight million people and a sampling of every kind of humanity... The contagion this evil brings spreads, slowly at first, then in geometric proportions: the city and the entire nation are threatened, then it will be the turn of the rest of the world.

A handful of people stand in the way of an Undead Prince's plan: a homicide detective who encountered that evil during his childhood, a priest condemned to death by an incurable disease, a television actor trying to snatch the woman he loves from a fate worse than death, a journalist used to stirring up the murky stuff, and a child who wants to avenge the murder of his parents. The weapons they fight with are few and inadequate, but their best weapon is faith...

After Bram Stoker's Dracula and Stephen King's The Nights of Salem, an absolute masterpiece of vampire literature from one of the undisputed masters of Horror.

Sed de Sangre es el tercer libro de Robert McCammon publicado en 1981.

Un mal tan antiguo como el mundo ha trasladado desde las tierras desoladas de un país de Europa del Este al caldero hirviente de la Ciudad de los Ángeles, más de ocho millones de personas y una muestra de todo tipo de humanidad... El contagio que trae este mal se propaga con él, primero lentamente, luego en proporción geométrica: la ciudad y la nación entera están amenazadas, luego le tocará al resto del mundo.

Un pequeño grupo de personas se interpone en el camino del plan de un Príncipe No-Muerto: un detective de homicidios que experimentó ese mal durante su infancia, un sacerdote condenado a muerte por una enfermedad incurable, un actor de televisión que intenta arrebatar a la mujer amada a un destino peor. que la muerte, un periodista acostumbrado a provocar problemas y un niño que quiere vengar el asesinato de sus padres. Las armas con las que luchan son pocas e inadecuadas, pero su mejor arma es la fe...

Después de Drácula de Bram Stoker y Salem's Lot de Stephen King, una obra maestra absoluta de la literatura vampírica de uno de los maestros indiscutibles del Terror.

That night there were demons in the hearth.

They were whirling, arching and sending sparks into the eyes of the boy who sat by the fire, his legs crossed beneath him in that unconscious way that boys have of being jointed. His chin supported by the palms of his hands, his elbows supported by his knees, he sat in silence, watching the flames come together, coalesce and burst into fragments that hissed secrets. He had turned nine only six days before, but now he felt grown up, because Dad had not yet come home and those demons in the fire were laughing.

While I'm gone you'll be the head of the house, Dad had said, wrapping a length of thick rope around the bear paw that was his hand. You are to look after your mother and make sure everything goes well while your uncle and I are away. Is that clear?

Yes, Dad.

And be sure to bring her wood when she asks, and arrange it well along the wall so it can dry. And anything else she asks you to do, you'll do, won't you?

I'll do it. It still seemed to him that he could see his father's cracked, wind-scarred face towering above him, and that he could feel his hand on his shoulder as rough as a fireplace stone. The grip of that hand had sent him a silent message: This is serious what I'm doing, kid. Make no mistake. Look after your mother and be careful.

The boy had said he understood and Dad had nodded in satisfaction.

The next morning he had watched through the kitchen window as Uncle Joseph hitched the two old grey and white horses to the wagon. The parents had secluded themselves, standing across the room near the door secured with a large bolted bar. Dad had donned the woollen cap and heavy sheepskin coat that Mom had packed for him years ago as a Christmas present, then slung the coiled rope around his shoulder. The boy had absent-mindedly eaten from a bowl of meat broth, knowing that they were whispering so that he would not hear them. But he knew that, if he did listen, he would not really want to know what they were saying to each other anyway. It's not fair! he told himself as he dipped his fingers in the broth and took a bite of meat. If I'm to be the head of the house, shouldn't I also know the secrets?

From the other end of the room, Mama's voice had suddenly risen uncontrollably. Let the others do it! Please. But Dad had taken her chin, holding her face up and looking tenderly into those morning-grey eyes. I must do it, he had said, and she looked as if she wanted to cry and couldn't. She had used up all her tears the night before, lying on the bed in the other room. The child had heard her throughout the night. It was as if the heavy hours of darkness were breaking her heart and there would never be enough hours of light to glue the pieces back together. No, no, Mum was now repeating, again and again, as if that word had something magical about it that could keep Dad from going outside in the snowy daylight, as if that word could have sealed the door, wood against stone, so that she could lock him in and the secrets out.

And, when she had fallen silent, Dad had taken the double-barrel from the rack beside the door. He had opened the weapon and loaded both chambers with buckshot, putting it back down carefully. Then he had held his mother close and kissed her and said: I love you. And she had clung to him like a second skin. And that's when Uncle Joseph had knocked on the door and called: Emil! We're ready to go!

Dad hugged her for a moment longer, then grabbed the rifle he had bought in Budapest and opened the door lock. He had stopped on the threshold and snowflakes swirled around him. André! he had said, and the boy had looked up. Take care of your mother and make sure this door stays locked. Understood?

Yes, father.

At the doorway, silhouetted against the background of the pale sky and the purple teeth of the distant mountain ranges, Dad had looked towards his wife and had spoken five words in a low voice. They were unclear, but the child had heard them, his heart pounding in dark unease.

Dad had said: Watch out for my shadow.

When he was gone, the hiss of the November wind filled the space he had occupied. Mama stood in the doorway, snow flaking on her long hair, growing older by the moment. She kept her eyes fixed on the wagon as the two men urged the horses along the paved path that would lead them to join the others. She stood there for a long time, almost defying the false, white purity of the world beyond. When the cart disappeared from sight, she turned, closed the door and bolted it. Then he turned his gaze to his son and said with a smile that looked more like a grimace: Do your homework now.

It had been three days since he had been away. Now the demons laughed and danced in the fire and something horrible, intangible had penetrated the house to sit in the empty chair in front of the fireplace, to sit between the child and the woman during their evening meals, to go after them like a gust of black ash lifted by an errant wind.

The corners of the two rooms of the house grew progressively colder as the log of wood slowly wore away, and the child could see a faint ghost of mist exhale swirling from his mother's nostrils every time she exhaled.

‘I'll get the axe and go make more wood,’ said the child, making to get up from the chair.

‘No!’ cried the mother immediately, and raised her head. Their gazes met and their grey eyes stared at each other for a few seconds. ‘The one we have is enough for the night. It's too dark outside now. You can wait until first light.’

‘But the one we have is not enough.’

‘I told you to wait until morning!’ She looked away almost immediately, as if ashamed. The knitting needles gleamed in the firelight as she slowly worked on a jumper for the child. When he sat down again, he saw the shotgun in the far corner of the room. It emanated a dull reddish light from the reflection of the fire, like a watchful eye in the darkness. And now in the fireplace the flame rose, whirled and shattered; the ash swirled in a vortex up the hood and out. The child stood watching; the heat cracked his cheekbones and the base of his nose, while his mother rocked in the chair behind him, glancing occasionally at her son's sharp profile.

In that fire the child saw images compose themselves, drawing a living mural: he saw a black wagon pulled by two white horses with funeral plumes, the cold breath coming out in little clouds. Inside that wagon a simple, small coffin. Other people followed the wagon, their boots crunching on the crust of snow. Muttered sounds. Secrets layered on faces. Half-closed, bewildered eyes stared at the grey-purple slopes of the Jaeger Mountains. The Griska boy lay in his coffin, and what remained of him was now carried in procession to the cemetery where the lelkész waited.

Death. To the child it had always seemed so cold, foreign and distant, something that did not belong to this world, not to the world of Mum and Dad, but to the one in which Grandma Elsa had lived when she was ill and had a yellowish complexion. Dad had used that word then: She is dying. When you are in the room with her, you have to be very good, because she can no longer sing for you and now she just wants to sleep.

For the child, death was a time when there were no more songs and you could only be happy when you closed your eyes. Now he stood staring at the hearse of his memories until the log crumbled and the tongues of flame scattered elsewhere. He remembered hearing whispers among the black-clad inhabitants of Krajeck: a terrible thing. He was only eight years old. Now he is with God.

God? Let us hope and pray that it is indeed God with whom Ivon Griska is now with.

The child remembered. He had seen the coffin lowered down with rope and pulley into the dark box dug into the ground, while the lelkész chanted blessings and waved the crucifix. The coffin was closed with nails and then wrapped with barbed wire. Before they began to cover it with shovelfuls of earth, the lelkész had made the sign of the cross and dropped the crucifix inside the grave. This had been a week ago, before the widow Janos disappeared; before the Sandor family vanished into the snowy Sunday night, abandoning everything they owned; before Johann the hermit reported seeing naked figures dancing on the windswept heights of the Jaeger Mountains and running together with the great forest wolves that haunted that bewitched mountain. Soon after Johann had also disappeared along with his dog, Vida. The child remembered the unusual hardness on his father's face, the flicker of some dark secret in his eyes. He had once heard Dad say to Mum: They are moving again.

In the fireplace the wood was moving and groaning. The child squinted and stepped back. Behind him, his mother's knitting needles were motionless; her head was raised towards the door and she was listening. The wind was roaring, carrying ice down the mountain. He would have to force himself to open the door the next morning, and the crust of ice would shatter like glass.

Dad should be home by now, the child told himself. It's so cold out there tonight, so cold.... Surely Daddy won't be long. There seemed to be secrets everywhere. Just the night before, someone had broken into Krajeck's cemetery and dug open twelve graves, including that of Ivon Griska. The coffins were gone, but rumour had it that the lelkész had found bones and skulls scattered in the snow.

Something banged loudly on the door, a noise like that of a hammer striking an anvil. Once. And then again. The woman jerked in her chair and turned around.

‘Daddy,’ cried the child joyfully. When he stood up, the strong clutches of heat on his face were forgotten. He headed for the door, but his mother grabbed him by the shoulder.

‘Hush!’ she whispered, and together they waited, with the Others banging on the door ~ a dull, heavy sound. The wind howled, and it sounded like Ivon Griska's mother wailing when the sealed coffin had been lowered into the frozen ground.

‘Open the door!’ said Dad. ‘Hurry up! I'm cold!’

‘Thank God!’ cried Mama. ‘Oh, thank God!’ She walked quickly to the door, pulled the bar away and threw it open. A torrent of snow whipped her face, the wind warped her eyes, nose and mouth. Dad, an indistinct shape in hat and coat, stepped forward in the faint light of the hearth and ice diamonds glittered in his eyebrows and beard. He took his mother in his arms, his massive body almost enveloping her. The child stepped forward to hug his father, grateful that he was back because being the man of the house was much harder than he had imagined. Dad approached, ran a hand through the child's hair and gave him a vigorous pat on the shoulder.

‘Thank God you're home!’ said Mum, clutching him. ‘It's over, isn't it?’

Esa noche había demonios en el hogar.

Se arremolinaban, se arqueaban y lanzaban chispas a los ojos del niño que estaba sentado junto al fuego, con las piernas cruzadas debajo de él en esa forma inconsciente en que los niños están articulados. Con la barbilla apoyada en las palmas de las manos y los codos apoyados en las rodillas, permaneció sentado en silencio, observando las llamas reunirse, fusionarse y estallar en fragmentos que silbaban en secreto. Había cumplido nueve años hacía apenas seis días, pero ahora se sentía mayor, porque papá aún no había regresado a casa y esos demonios en el fuego se reían.

Mientras yo no esté, tú serás el jefe de la casa, había dicho papá, enrollando un trozo de cuerda gruesa alrededor de la zarpa de oso que era su mano. Debes cuidar de tu madre y asegurarte de que todo vaya bien mientras tu tío y yo estemos fuera. ¿Claro?

Sí, papá.

Y asegúrate de traer la madera cuando ella te lo pida y colócala bien a lo largo de la pared para que se seque. Y cualquier otra cosa que te pida, lo harás, ¿verdad?

Lo haré. Todavía le parecía ver el rostro de su padre, agrietado y curtido por el viento, alzándose sobre él y sentir su mano sobre su hombro, áspera como la piedra de una chimenea. El apretón de esa mano le había enviado un mensaje silencioso: Esto es un asunto serio, muchacho. No cometas ningún error. Cuida a tu madre y ten cuidado.

El niño dijo que entendía y papá asintió con satisfacción.

A la mañana siguiente había observado desde la ventana de la cocina cómo el tío Joseph enganchaba los dos viejos caballos grises y blancos al carro. Los padres se habían retirado y se habían parado al otro lado de la habitación, cerca de la puerta asegurada con una gran barra atornillada. Papá se había puesto el gorro de lana y el pesado abrigo de piel de oveja que mamá le había hecho años atrás como regalo de Navidad, y luego se había puesto la cuerda enrollada alrededor de su hombro. El niño había mordisqueado distraídamente un plato de caldo de res, sabiendo que estaban susurrando para que él no los escuchara. Pero sabía que si escuchaba, todavía no querría saber realmente lo que estaban diciendo. ¡No es justo! se dijo mientras mojaba los dedos en el caldo y sacaba un bocado de carne. Si tengo que ser el cabeza de familia, ¿no debería conocer también los secretos?

Desde el otro extremo de la habitación, la voz de mamá de repente se salió de control. ¡Que otros lo hagan! Te lo ruego. Pero papá la había tomado por la barbilla, sosteniendo su rostro en alto y mirándola con ternura a esos ojos grises como la mañana. Tengo que hacerlo, dijo, y parecía que quería llorar y no podía. Había agotado todas sus lágrimas la noche anterior, acostada en la cama de la otra habitación. El niño lo había oído toda la noche. Era como si las pesadas horas de oscuridad le estuvieran rompiendo el corazón y nunca hubiera suficientes horas de luz para volver a unir las piezas. No, no, no, repetía ahora mamá, una y otra vez, como si esa palabra tuviera alguna magia que pudiera impedir que papá saliera a la luz del día nevado, como si esa palabra pudiera sellar la puerta, madera contra piedra, para poder para encerrarlo dentro y sacar los secretos.

Y, cuando ella se quedó en silencio, papá había cogido la escopeta del estante al lado de la puerta. Abrió el arma, cargó ambas recámaras con perdigones y la volvió a dejar con cuidado. Luego abrazó a su madre, la besó y le dijo: Te amo. Y ella se aferró a él como una segunda piel. Y en ese momento el tío Joseph llamó a la puerta y llamó: ¡Emil! ¡Estamos listos para partir!

Papá la abrazó un momento más y luego agarró el rifle que había comprado en Budapest y abrió la cerradura de la puerta. Se había detenido en la puerta y los copos de nieve se arremolinaban a su alrededor. ¡André! había dicho, y el niño había levantado la vista. Cuida a tu madre y asegúrate de que esta puerta permanezca bien cerrada. ¿Comprendido?

Sí, papá.

En la puerta, recortada contra el cielo pálido y los dientes morados de las lejanas cadenas montañosas, papá miró a su esposa y dijo cinco palabras en voz baja. No estaban claros, pero el niño los había percibido y su corazón latía con oscura inquietud.

Papá había dicho: Cuidado con mi sombra.

Cuando se fue, el silbido del viento de noviembre llenó el espacio que había ocupado. Mamá estaba en la puerta, la nieve caía sobre su largo cabello, envejeciéndola más a cada momento. Mantuvo los ojos fijos en el carro mientras los dos hombres impulsaban a los caballos por el camino pavimentado que los llevaría a unirse a los demás.

Permaneció allí durante mucho tiempo, casi como si desafiara la falsa y blanca pureza del mundo más allá de esa puerta. Cuando el carro desapareció de su vista, se volvió, cerró la puerta y echó el cerrojo. Luego miró a su hijo y le dijo con una sonrisa que más bien parecía una mueca: Haz tu tarea ahora.

Llevaba tres días ausente. Ahora los demonios reían y bailaban en el fuego y algo horrible, intangible había entrado en la casa para sentarse en la silla vacía frente a la chimenea, para sentarse entre el niño y la mujer durante la cena, para seguirlos como una ráfaga. de ceniza negra levantada por un viento errante.

Los rincones de las dos habitaciones de la casa se fueron volviendo progresivamente fríos a medida que el tronco de madera se desgastaba lentamente, y el niño podía ver un leve fantasma de niebla exhalando y arremolinándose de las fosas nasales de su madre cada vez que ésta exhalaba.

"Tomaré el hacha e iré a buscar más leña", dijo el niño, comenzando a levantarse de la silla.

"¡No!", gritó la madre inmediatamente y levantó la cabeza. Sus miradas se encontraron y sus ojos grises se miraron fijamente durante unos segundos. «Lo que tenemos es suficiente para pasar la noche. Afuera ya está demasiado oscuro. Puedes esperar hasta las primeras luces del día".

«Pero lo que tenemos no es suficiente…».

"¡Te dije que esperaras hasta mañana!" Apartó la mirada casi de inmediato, como si estuviera avergonzado. Las agujas de tejer brillaban a la luz del fuego mientras ella tejía lentamente un suéter para el bebé. Cuando volvió a sentarse, vio la escopeta en el rincón más alejado de la habitación.

Emitía una luz rojiza y apagada por el reflejo del fuego, como un ojo vigilante en la oscuridad. Y ahora en la chimenea la llama se elevó, se arremolinó y se hizo añicos; la ceniza subió por el capó y salió. El niño miró; el calor le recorría los pómulos y el puente de la nariz, mientras su madre se mecía en la silla detrás de él, mirando de vez en cuando el perfil afilado de su hijo.

En aquel incendio el niño vio imágenes componiendo, dibujando un mural vivo: vio un carro negro tirado por dos caballos blancos con penachos fúnebres, el aliento frío saliendo en nubes. Dentro de ese carro un sencillo y pequeño ataúd. Más personas siguieron al carro, sus botas crujieron sobre la capa de nieve. Sonidos murmurados. Secretos superpuestos en los rostros. Ojos entrecerrados y temerosos que contemplan las laderas gris violáceas de las montañas Jaeger. El niño Griska yacía en el ataúd, y lo que quedaba de él ahora fue llevado en procesión al cementerio donde esperaba el lelkész.

Muerte. A la niña siempre le había parecido tan fría, extraña y distante, algo que no pertenecía a este mundo, no al mundo de la madre y el padre, sino a aquel en el que había vivido la abuela Elsa cuando estaba enferma y tenía el rostro amarillento. tez. Papá había usado esa palabra entonces: se está muriendo. Cuando estés en la habitación con ella, tienes que estar muy callado, porque ella ya no puede cantarte y ahora sólo quiere dormir.

Para el niño, la muerte era un momento en el que ya no había canciones y sólo se podía ser feliz cuando cerraba los ojos. Ahora se quedó mirando el coche fúnebre de sus recuerdos hasta que el tronco se desmoronó y las lenguas de fuego se esparcieron por otros lados. Recordó haber oído susurros entre los habitantes vestidos de negro de Krajeck: Algo terrible. Tenía sólo ocho años. Ahora está con Dios.

¿Dios? Esperemos y oremos para que realmente sea Dios con quien está ahora Ivon Griska.

El niño lo recordó. Había visto bajar el ataúd mediante cuerdas y poleas hasta la caja oscura excavada en el suelo, mientras los lelkész cantaban bendiciones y agitaban el crucifijo. El ataúd había sido cerrado con clavos y luego envuelto con alambre de púas. Antes de empezar a cubrirlo con palas de tierra, el lelkész había hecho la señal de la cruz y había dejado caer el crucifijo en el interior de la tumba. Esto había ocurrido hacía una semana, antes de que desapareciera la viuda Janos; antes de que la familia Sandor desapareciera en la nevada noche del domingo, abandonando todo lo que poseían; antes de que Johann el ermitaño informara haber visto figuras desnudas bailando en las alturas azotadas por el viento de las montañas Jaeger y corriendo junto con los grandes lobos del bosque que atormentaban esa montaña encantada. Poco después, Johann también desapareció junto con su perro Vida. El niño recordó la dureza inusual en el rostro de su padre, la emoción de algún oscuro secreto en sus ojos. Una vez escuchó a papá decirle a mamá: Estoy en movimiento otra vez.

En la chimenea la leña se movía y gemía. El niño entrecerró los ojos y dio un paso atrás. Detrás de ella, las agujas de tejer de su madre estaban quietas; su cabeza estaba inclinada hacia la puerta y estaba escuchando. El viento rugió, arrastrando el hielo montaña abajo. A la mañana siguiente, habría tenido que forzarse a abrir la puerta y la corteza de hielo se habría hecho añicos como cristal.

Papá ya debería estar en casa, se dijo el niño. Hace tanto frío ahí afuera esta noche, tanto frío... Seguro que papá no tardará. Parecía haber secretos por todas partes. La noche anterior alguien había entrado en el cementerio de Krajeck y abierto y desenterrado doce tumbas, entre ellas la de Ivón Griska. Los ataúdes habían desaparecido, pero corrían rumores de que los lelkész habían encontrado huesos y cráneos esparcidos en la nieve.

Algo golpeó la puerta, un sonido como el de un martillo golpeando un yunque. Una vez. Y luego otra vez. La mujer saltó de su silla y se dio la vuelta.

“Papá”, gritó alegremente el niño. Cuando se puso de pie, las fuertes rayas de calor en su rostro quedaron olvidadas. Se dirigió hacia la puerta, pero su madre lo agarró del hombro.

“¡Cállate!”, susurró, y juntos esperaron, mientras el Otro llamaba a la puerta, un sonido sordo y pesado. El viento aulló y sonó como el gemido de la madre de Ivón Griska cuando el ataúd sellado fue bajado al suelo helado.

"¡Abre la puerta!" dijo papá. "¡Apresúrate! ¡Tengo frío!".

"¡Gracias a Dios!", gritó la madre. «¡Oh, gracias a Dios!».

Rápidamente fue hacia la puerta, apartó la barra y la abrió. Un torrente de nieve le azotó la cara, el viento le deformó los ojos, la nariz y la boca. Padre, una figura sombría con sombrero y abrigo, avanzó hacia la tenue luz del hogar, con diamantes de hielo brillando en sus cejas y barba. Tomó a su madre en sus brazos y su enorme cuerpo casi la envolvió. El niño dio un paso adelante para abrazar a su padre, agradecido de estar de regreso porque ser el hombre de la casa era mucho más difícil de lo que había imaginado. Papá se acercó, pasó una mano por el pelo del niño y le dio una vigorosa palmada en el hombro.

A book of unusual narrative breadth that arouses in the reader a vague perception of the unreal. The very realistic settings create a very sincere urban/narrative fabric that mixes the narration with the explanatory synthesis of a generation and a universe. Evil (physical, mental, cultural) permeates the lives of the protagonists so deeply that it makes them more attentive to the manifestations of an even older evil that at times takes on the contours of the fearful terror of the unknown and the nineteenth-century sublime. Only those who are totally immersed in it can only collapse into it until they are submerged and destroyed.

The will of the soul is the characteristic of the protagonists who, despite the "classic" anti-vampire remedies (garlic, holy water, stakes and crosses) demonstrate a perhaps more obscured faith. God remains hidden from the eyes of the reader/narrator. There is almost an escapological sense in the final pages of the novel and Nature, in its extreme truth, relieves the Supreme Factor from the burdensome task of actively intervening. The physical destruction of the world/narrative horizon known to the reader becomes the origin of the New.

The diversity of the work lies precisely in the total absence of a sacred/religious message that therefore borders on trust in a human and only human redemption. Special attention can be paid to the protagonists: a detective who has experienced this ancient scourge at a young age and who seems to have a higher-than-average capacity for perception; a young dissatisfied journalist who knows the horror of everyday life up close; a priest condemned by an incurable disease and finally a child who somehow embodies the frustrations and dissatisfactions of the young American generation (and not only). Everyone in their diversity knows evil and everyone in their own way rebels against it with the sole force of will, challenging fate and the total absence of divine support. The author's extreme synthesis is represented in the great wave that hits L.A. where water, the cradle of life and its origin, will sweep away and purify Evil.

Un libro con un alcance narrativo inusual que despierta en el lector la vaga percepción de lo irreal. Los escenarios, muy realistas, crean un tejido urbano/narrativo muy sincero que mezcla la narración con la síntesis explicativa de una generación y un universo. El mal (físico, mental, cultural) impregna tan profundamente la vida de los protagonistas que les hace estar más atentos a las manifestaciones de un mal aún más antiguo que a veces adquiere los contornos del terror temible de lo desconocido y de lo sublime del siglo XIX. . Sólo aquellos que están totalmente sumergidos en él pueden colapsar en él hasta quedar sumergidos y destruidos.

La voluntad del alma es la característica de los protagonistas que, a pesar de los remedios "clásicos" antivampiros (ajo, agua bendita, estacas y cruces) demuestran una fe quizás más nublada. Dios permanece oculto a los ojos del lector/narrador. Hay casi un sentido escapológico en las páginas finales de la novela y la Naturaleza, en su extrema verdad, libera al Factor Supremo de la pesada tarea de intervenir activamente. La destrucción física del horizonte mundial/narrativo conocido por el lector se convierte en el origen de lo Nuevo.

La diversidad de la obra reside precisamente en la ausencia total de un mensaje sacro/religioso que, por tanto, raya en la confianza en una redención humana y sólo tal. Se puede prestar especial atención a los protagonistas: un detective que se encontró con este antiguo flagelo siendo joven y que parece tener una capacidad de percepción superior a la media; un joven periodista insatisfecho que conoce de primera mano el horror de la vida cotidiana; un sacerdote condenado por una enfermedad incurable y finalmente un niño que de alguna manera encarna las frustraciones y la insatisfacción de la joven generación estadounidense (y no sólo) Cada uno en su diversidad conoce el mal y cada uno a su manera se rebela contra él con sólo la fuerza de voluntad. destino desafiante y la ausencia total de apoyo divino. La síntesis extrema del autor queda representada en la gran ola que azota Los Ángeles. donde el agua, cuna de la vida y su origen, barrerá y purificará el Mal.

Source images / Fuente imágenes: Robert McCammon.

Fuente de la imagen banner final post / Image source banner final post.

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content