As is well known, New England is that region of the United States located in the northeastern part of the country where the Pilgrim Fathers from England landed in 1620, founding the first great Puritan community in the New World. The region, bordering the Atlantic, includes the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut and Rhode Island. And even after these few lines, the regular American horror con-sumer would feel at home: King's Maine, Massachusetts' Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe, Rhode Island's Lovecraft... But, after bothering with the classics, Lincoln Child was born in Connecticut, Christopher Golden again in Massachusetts, the unknown (to us) F. Brett Cox comes from Vermont, and even Dan Brown - who has nothing to do with horror, but oozes Gothic - was born in New Hampshire.

It is not a matter of trivial statistical registry, but rather of the fact that the rotten ‘heart’ of the American Gothic, where the flames of Hell burn eternally and God never reveals himself to be just and merciful, but always a ruthless avenger, was born, has changed and still lives (there is a very large Horror Writers Association in New England). It is the founding Puritanism, characterised by the extreme orthodoxy of early New England, which had to come to terms, not entirely resolving them, with the witchcraft paranoia of the 17th century, immortalised in literature by Nathaniel Hawthorne and Arthur Miller with The Scarlet Letter and The Crucible.

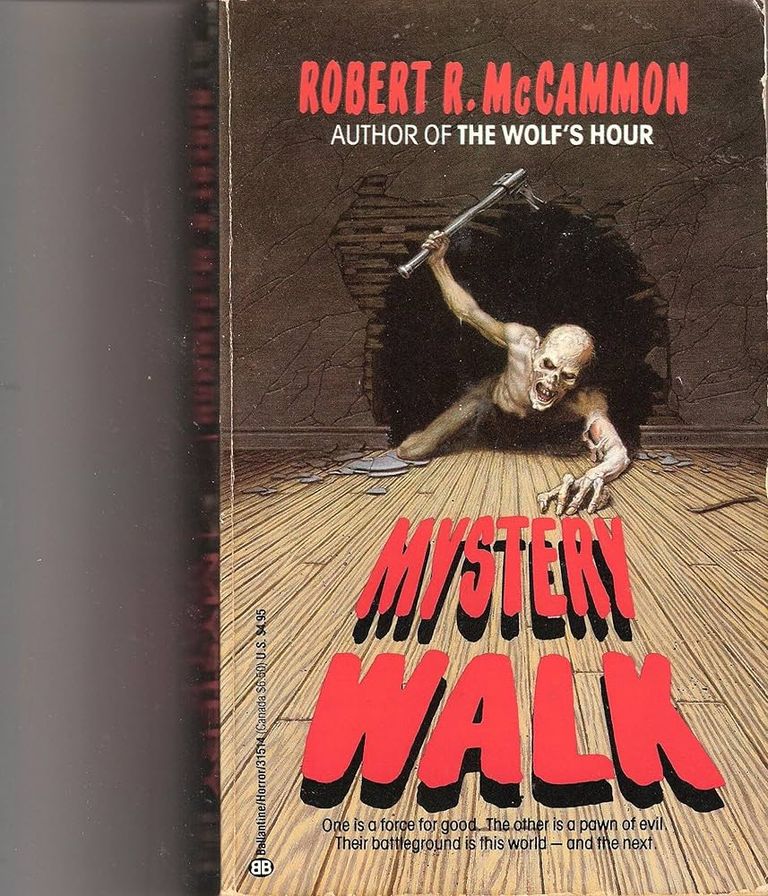

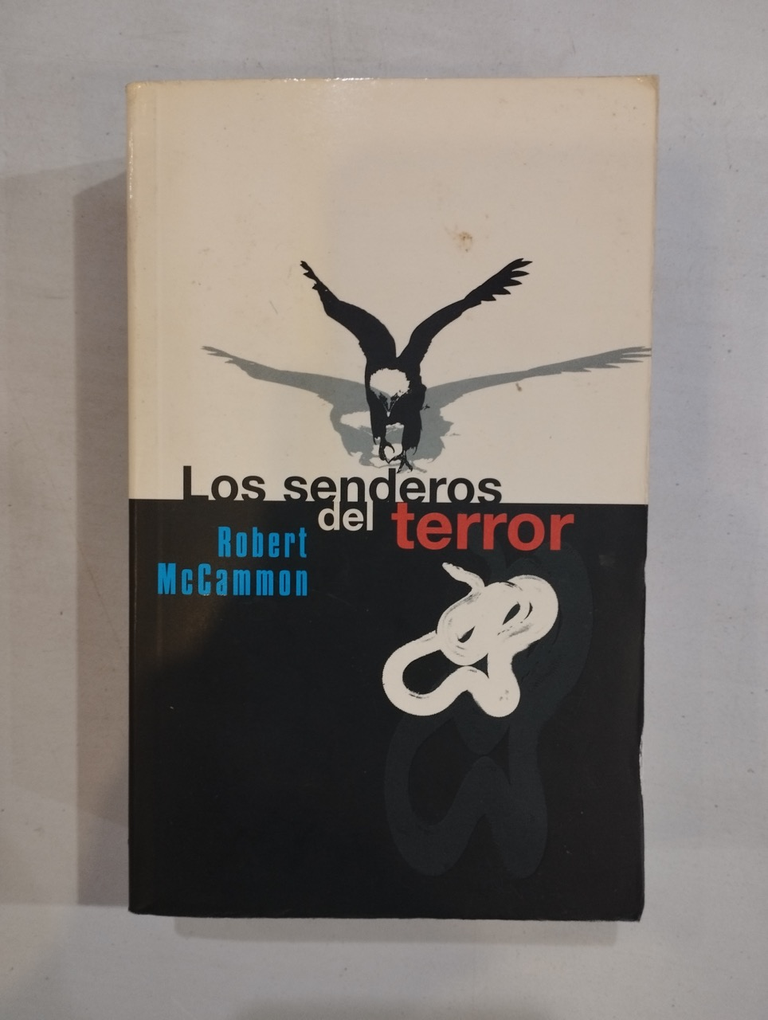

For those who go to the cinema, there are a few films based on the former, one signed by Wim Wenders and the last one released by Roland Joffé, while from Miller's text The Seduction of Evil - The Crucible by Nicholas Hytner was adapted. And this cinematic reference is no coincidence, because the New England aesthetic, which always coincides with the substance, also passes through here: through those closed communities, with women and men dressed in black in the typical uniforms of the pilgrims, where guilt and sin, always cited as bogeymen, make the Victorians of nineteenth-century England look like progressive leftists, and where the Devil and Evil, not by chance capitalised, like to show off more because they are always called into question. There is an ideal ‘Gothic’ line that passes between yesterday and today, from films such as Leo Penn's The Dark Secret of Harvest Home, Robert Mulligan's Who Is the Other One?, Wes Craven's Deadly Blessing, Sam Raimi's The Gift, without forgetting the almost always unfortunate fallout of King's various Children of the Corn and the relatively recent The Village by M. Night Shyamalan. Night Shyamalan's The Village: it is always about the truest and most tormented soul of Gothic New England, where diversity and modernity are branded as ‘witchcraft’ and intruders meet a nasty end. The same spirit that animates Robert McCammon's The Dark Way.

Como es bien sabido, Nueva Inglaterra es la región de Estados Unidos situada al noreste del país donde desembarcaron los Padres Peregrinos procedentes de Inglaterra en 1620, fundando la primera gran comunidad puritana del Nuevo Mundo. La región, ribereña del Atlántico, incluye los estados de Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut y Rhode Island. E incluso después de estas pocas líneas, el consumidor habitual de terror estadounidense se sentiría como en casa: el Maine de King, los Nathaniel Hawthorne y Edgar Allan Poe de Massachusetts, el Lovecraft de Rhode Island... Pero, después de molestar a los clásicos, Lincoln Child nació en Connecticut, Christopher Golden de nuevo en Massachusetts, el desconocido (para nosotros) F. Brett Cox viene de Vermont, e incluso Dan Brown -que no tiene nada que ver con el horror, pero rezuma gótico- nació en New Hampshire.

No se trata de un registro estadístico trivial, sino del hecho de que el «corazón» podrido del gótico americano, donde las llamas del Infierno arden eternamente y Dios nunca se revela justo y misericordioso, sino siempre un vengador despiadado, nació, ha cambiado y aún vive (hay una Asociación de Escritores de Terror muy grande en Nueva Inglaterra). Es el puritanismo fundacional, caracterizado por la extrema ortodoxia de la Nueva Inglaterra primitiva, que tuvo que vérselas, sin resolverlas del todo, con la paranoia de la brujería del siglo XVII, inmortalizada en la literatura por Nathaniel Hawthorne y Arthur Miller con La letra escarlata y El crisol.

Para los que vayan al cine, hay algunas películas basadas en la primera, una firmada por Wim Wenders y la última estrenada por Roland Joffé, mientras que del texto de Miller se adaptó La seducción del mal - El crisol, de Nicholas Hytner. Y esta referencia cinematográfica no es casual, porque la estética de Nueva Inglaterra, que siempre coincide con la sustancia, también pasa por aquí: por esas comunidades cerradas, con mujeres y hombres vestidos de negro con los uniformes típicos de los peregrinos, donde la culpa y el pecado, siempre citados como hombres del saco, hacen que los victorianos de la Inglaterra decimonónica parezcan izquierdistas progresistas, y donde al Diablo y al Mal, no por casualidad con mayúsculas, les gusta más lucirse porque siempre se les pone en entredicho. Hay una línea «gótica» ideal que transcurre entre el ayer y el hoy, a partir de películas como El oscuro secreto del hogar de la cosecha, de Leo Penn, ¿Quién es el otro?, de Robert Mulligan, Bendición mortal, de Wes Craven, El regalo, de Sam Raimi, sin olvidar las casi siempre desafortunadas secuelas de los diversos Niños del maíz, de King, y la relativamente reciente La aldea, de M. Night Shyamalan. Night Shyamalan: siempre se trata del alma más verdadera y atormentada de la Nueva Inglaterra gótica, donde la diversidad y la modernidad son tachadas de «brujería» y los intrusos encuentran un desagradable final. El mismo espíritu que anima El camino oscuro, de Robert McCammon.

McCammon, however, goes further. In order for his characters to interact in this great theatre of passions and drives that is The Dark Way, the writer needs a genuinely conservative location, where the widespread sense of social intolerance can express itself at its most hateful in its racist uniform. New England on this front cannot sto-rically be of any help to him, nor could it function credibly, having played a key role in the abolition of slavery during the 19th century. Better in this respect, also because McCammon was born there and knows it well, is the conservative and isolationist Alabama of the decades in which the choral story told in The Dark Way is set (the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s). That Alabama where the Ku Klux Klan was founded and where blacks still have their too many problems. A region where even a white, moderately progressive priest can happen to be sprinkled with pitch and feathers, because it is said of him that he ‘doesn't dis-de-gna the negro pussy’.

The background is defined. And, at this point, the prefect does not have to commit the mortal sin of telling you about the book. But to attempt, as far as possible, to draw the lines of an effective cinematic coming soon. Let's say that, as almost always with McCammon, at the third line we are immediately ‘in medias res’, pleasantly mired in that Puritan humus where the New England e-redemption and the guilt of the Salem tragedy are mediated by those many ‘prohibitions’, whose most effective tòpos is the ‘dark and forbidden place where one must not go’, with all the metaphors one can propose in this regard. A region - an America - where religious fanaticism can kill by overdose and where an archaic ‘founding’ conflict overturns the parameters of Good and Evil by 360°: it is that America that fears and hates everything it does not understand and that is not homologated to a ‘superior’ idea of social conformity. Women, blacks, kids who are ‘out of the chorus’: all enemies in this archaic and almost tribal society, where the typical ideas of puritanism of Jesuitical origin (still well present in certain basic and ‘popular’ religiosity) find their place, for which ma-sickness only enters the body following the ‘sin committed’, and where the sense of guilt incorporated in the soul takes over as an eternal and lacerating doubt.

McCammon, sin embargo, va más allá. Para que sus personajes interactúen en este gran teatro de pasiones y pulsiones que es El camino oscuro, el escritor necesita un lugar genuinamente conservador, donde el sentimiento generalizado de intolerancia social pueda expresarse en su más odioso uniforme racista. Nueva Inglaterra, en este frente, no puede serle de ninguna ayuda, ni podría funcionar de forma creíble, al haber desempeñado un papel clave en la abolición de la esclavitud durante el siglo XIX. Mejor en este sentido, también porque McCammon nació allí y la conoce bien, es la Alabama conservadora y aislacionista de las décadas en las que se desarrolla la historia coral que se cuenta en El camino oscuro (los años cincuenta, sesenta y principios de los setenta). Esa Alabama donde se fundó el Ku Klux Klan y donde los negros siguen teniendo sus demasiados problemas. Una región en la que hasta un cura blanco, medianamente progresista, puede resultar salpicado de brea y plumas, porque se dice de él que «no desdeña a el coño negro».

El trasfondo está definido. Y, llegados a este punto, el prefecto no tiene que cometer el pecado mortal de hablarte del libro. Sino de intentar, en la medida de lo posible, trazar las líneas de un efectivo pronto cinematográfico. Digamos que, como casi siempre con McCammon, a la tercera línea estamos inmediatamente «in medias res», gratamente enfangados en ese humus puritano donde la e-redención de Nueva Inglaterra y la culpa de la tragedia de Salem están mediadas por esas muchas «prohibiciones», cuyo tòpos más eficaz es el «lugar oscuro y prohibido donde no se debe ir», con todas las metáforas que se puedan proponer al respecto. Una región -una América- donde el fanatismo religioso puede matar por sobredosis y donde un arcaico conflicto 'fundacional' trastoca los parámetros del Bien y del Mal en 360°: es esa América que teme y odia todo lo que no comprende y que no está homologado a una idea 'superior' de conformidad social. Las mujeres, los negros, los chicos que se 'salen del coro': todos enemigos en esta sociedad arcaica y casi tribal, en la que encuentran su lugar las ideas típicas del puritanismo jesuítico (aún muy presente en cierta religiosidad básica y 'popular'), para la que la ma-enfermedad sólo entra en el cuerpo tras el 'pecado cometido', y donde el sentimiento de culpa incorporado al alma se apodera de él como una duda eterna y lacerante.

In this swamp, which could not be more gothic, familiar echoes are picked up and cultural tokens are paid in that great and pleasant game of cross-references that is contemporary horror. See for yourself if other authors, films or currents come to mind... The Evil that is a shape-shifting creature and as-sume all the aspects it wants (‘... that never gives up and adapts to the changes of time’), that is, it vampires forms, but its typical substance is a colour, black. Supernatural powers are distributed (by whom?) by predestination, with no possibility of free will. The ‘gift’ (the Gift) that chooses you and often, especially because of its negative social repercussions, is anything but a gift. Hence the extreme loneliness of those who have and express extrasensory powers: Billy, one of the young protagonists, possesses - like the famous child in Shyamalan's film - the Sixth Sense and can see the dead, especially the restless ones. And he can help them find their way back to the right path. But all this turns out to be a sentence for him to live border-line, on the border between life and death. And the ‘small town’ that cannot be missed is called, as it happens, Hawthorne. And the ancient red-skinned folklore, in which you find a universal God who addresses everyone, whites and blacks. And good, ancient ‘witchcraft’, which cleverly uses herbs to heal the body's ills. And, again, the curse on the road in which the wrath of a ghost of the road causes chain car accidents.

But it doesn't end there. Because we also come across a very good curse house, the ‘Booker house’ that looms over Hawthorne like Micha-el Myers' in Haddonfield. We have the ultra-classic theme, especially in the ci-nema, of prom night, the prom that in American Gothic has become, for the last thirty years, the chosen moment for the unleashing of the forces of Evil. Let's add the melancholic travelling funfair, the funhouse that takes us back to Bradbury and Tobe Hooper, with its load of freaks, Mr Dark, ‘fake’ shows with ‘real’ ghosts, Doctor Mirakle, circuses of horrors and haunted merry-go-rounds. From Pennywise to Carnivale to Steven Spielberg's Taken, it is a vast and imaginative territory from which many horror writers have no intention of breaking free. Here and there a Grindhouse-like atmosphere. Sexuality, a touch of snuff, an invisible ‘double’... Is something still missing? Yes.

En este pantano, que no puede ser más gótico, se recogen ecos familiares y se pagan fichas culturales en ese gran y placentero juego de referencias cruzadas que es el terror contemporáneo. Compruebe usted mismo si le vienen a la cabeza otros autores, películas o corrientes... El Mal que es una criatura que cambia de forma y as-sume todos los aspectos que quiere («... que nunca se rinde y se adapta a los cambios del tiempo»), es decir, vampiriza formas, pero su sustancia típica es un color, el negro. Los poderes sobrenaturales son distribuidos (¿por quién?) por predestinación, sin posibilidad de libre albedrío. El «don» (el Don) que te elige y a menudo, sobre todo por sus repercusiones sociales negativas, es cualquier cosa menos un don. De ahí la extrema soledad de quienes tienen y manifiestan poderes extrasensoriales: Billy, uno de los protagonistas, posee -como el famoso niño de la película de Shyamalan- el Sexto Sentido y puede ver a los muertos, sobre todo a los inquietos. Y puede ayudarles a encontrar el camino de vuelta a la senda correcta. Pero todo esto resulta ser para él una condena a vivir al límite, en la frontera entre la vida y la muerte. Y el «pequeño pueblo» que no puede faltar se llama, casualmente, Hawthorne. Y el antiguo folclore de los pieles rojas, en el que se encuentra un Dios universal que se dirige a todos, blancos y negros. Y la buena y antigua «brujería», que utiliza hábilmente hierbas para curar los males del cuerpo. Y, de nuevo, la maldición en la carretera, en la que la ira de un fantasma de la carretera provoca accidentes de coche en cadena.

Pero la cosa no acaba ahí. Porque también nos encontramos con una casa maldita muy buena, la «casa Booker» que se cierne sobre Hawthorne como la de Micha-el Myers en Haddonfield. Tenemos el tema ultraclásico, sobre todo en el ci-nema, de la noche del baile de graduación, el baile que en el gótico americano se ha convertido, desde hace treinta años, en el momento elegido para el desencadenamiento de las fuerzas del Mal. Añadamos el melancólico parque de atracciones ambulante, el funhouse que nos retrotrae a Bradbury y Tobe Hooper, con su carga de freaks, Mr Dark, espectáculos «falsos» con fantasmas «reales», Doctor Mirakle, circos de los horrores y tiovivos embrujados. De Pennywise a Carnivale, pasando por Taken de Steven Spielberg, es un territorio vasto e imaginativo del que muchos escritores de terror no tienen intención de liberarse. Aquí y allá una atmósfera tipo Grindhouse. Sexualidad, un toque de tabaco, un «doble» invisible... ¿Aún falta algo? Sí.

Reading it in 2008, The Dark Way reverberates with King- and Lan-Sdalian echoes. The Children of the Corn, The Dead Zone and even Pet Sematary come to mind (Toby the dog who comes back alive after being hit by a truck looks like the canine version of Church the cat), teenagers with paranormal powers and parents of the same (the pious Reverend Falconer is the male alterity of Carrie White's mother), and again children struggling against racist obscurantism like In the bottom of the swamp by Big-de Joe.

But, mind you, The Dark Way was written in the early 1980s, and among the many ingredients of the dish it expresses a social, denunciatory function of horror that comes to us from times long past. In the pillory, still topical, the religious fanaticism of the television preachers, much more interested in business than in the salvation of the pious souls who listen to them; those who always invoke Satan as a social bogeyman and perhaps use him in secret; those for whom, of course, rock is the devil's music; those who, self-proclaimed ‘Crusaders of Good’, burn books and records in the public square (like Nazis of not entirely buried memory and certain Islamic fringes); those for whom the long-haired Beatles, Cream, Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs (Wooly Bully! ) are all mobs who produce ‘sinful junkie music’; those who represent a not-so-silent and undoubtedly armed majority; those who, as mad telepredicators and great mass manipulators, are in the end the true agents of Evil.

Leída en 2008, La vía oscura resuena con ecos kingianos y lan-sdalianos. Me vienen a la mente Los chicos del maíz, La zona muerta e incluso Pet Sematary (Toby, el perro que vuelve vivo tras ser atropellado por un camión, se parece a la versión canina del gato Church), adolescentes con poderes paranormales y padres de los mismos (el piadoso reverendo Falconer es la alteridad masculina de la madre de Carrie White), y de nuevo niños que luchan contra el oscurantismo racista como En el fondo del pantano de Big-de Joe.

Pero, ojo, Los Senderos del terror fue escrito a principios de los ochenta, y entre los muchos ingredientes del plato expresa una función social, de denuncia del horror, que nos viene de tiempos pasados. En la picota, aún de actualidad, el fanatismo religioso de los predicadores televisivos, mucho más interesados en el negocio que en la salvación de las almas piadosas que les escuchan; aquellos que siempre invocan a Satán como hombre del saco social y tal vez lo utilizan en secreto; aquellos para los que, por supuesto, el rock es la música del diablo; aquellos que, autoproclamados «cruzados del bien», queman libros y discos en la plaza pública (como los nazis de memoria no del todo enterrada y ciertas franjas islámicas); aquellos para los que los Beatles de pelo largo, Cream, Sam the Sham y los Pharaohs (¡Wooly Bully! ) son todos gentuza productora de «música yonqui pecaminosa»; aquellos que representan a una mayoría no tan silenciosa e indudablemente armada; aquellos que, como locos telepredicadores y grandes manipuladores de las masas, son al final los verdaderos agentes del Mal.

It this point, I am dutifully silent about the book. I will mention, if I can, something about McCammon that has not yet been said. To two greats who have marked like very few others the history of noir and thriller publishing in Italy, Laura Grimaldi and Marco Tropea, we owe the entry of the author of La Via Oscura into our country. It was the late 1980s and the Milanese couple, having just resigned from Mondadori, had set up a new publishing house whose choices would be seminal for the future of ‘pop’ genres orbiting the pleasantly confused magma of the thriller. The hard-boiled, the crime novel, science fiction, Italian noir, but also horror, all converged in a single acronym, Interno Giallo, to remind the world that we are still dealing with ‘tension’ literature. It was thanks to G & T that we got to know James Ellroy, Andrew Vachss, Jerome Charyn and (excuse me if this is not enough) the beginnings of Giancarlo De Cataldo and Pino Ca-cucci. For horror stricto sensu, they focused on unknown names of extraordinary class such as K.W. Jeter, Jack Curtis, Stephen Gallagher and (here we come) Robert McCammon. An author, as has been written, a native of Ala-bama, a favourite of the Gargoyle house and much loved in Italy, who made his debut with his tenth title, Mine. If remembering him does justice to Gri-maldi and Tropea (who delightfully entitled the book in Italian Mary Terror, playing on the name and surname of the psychopathic protagonist Mary Terrell), the selective paradox - and distressing for so many other Anglo-Saxon writers - that the laws of the market impose, at least here in Italy, jumps clearly to the eye. Where precisely you can be translated and known on your tenth title. Interno Giallo did not limit itself to Mine and proposed in ‘92 Boy's Life, an extraordinary response, steeped in love for the cinema and nostalgia, to King's Different Seasons, entitled The Belly of the Lake. It was McCammon's second book in Italy, the eleventh in America (where it had been published the year before), apart from many stories scattered here and there in various anthologies.

Although the ‘solo’ experience of Interno Giallo would soon cease, absorbed by Mondadori and transformed into a series, McCammon's pass in Italy was by then well established. And, in evident chronological disorder, the following titles appeared in close succession: Baal (his debut title), the fluvial and apocalyptic Swan Song (Tenebre) and then, gradually diluted, the science-fiction Stinger (L'invasione), the ‘realistic’ action Gone South (L'inferno nella palude) and Bethany's Sin (Loro attendono, a title that is as paradigmatic as ever, given that it was published in the USA in 1980 and in Italy in ‘96). Then silence, a black-out that was actually a perfect mirror of the ‘growth crisis’ that struck on the other side.

En este punto, guardo obediente silencio sobre el libro. Mencionaré, si puedo, algo sobre McCammon que aún no se ha dicho. A dos grandes que han marcado como pocos la historia de la novela negra y de suspense en Italia, Laura Grimaldi y Marco Tropea, debemos la entrada del autor de La Vía Oscura en nuestro país. Eran finales de los años 80 y la pareja milanesa, que acababa de dimitir de Mondadori, había creado una nueva editorial cuyas decisiones serían determinantes para el futuro de los géneros «pop» que orbitaban alrededor del magma agradablemente confuso del thriller. El hard-boiled, la novela negra, la ciencia ficción, el noir italiano, pero también el terror, convergieron en un único acrónimo, Interno Giallo, para recordar al mundo que todavía se trata de literatura de «tensión». Gracias al G & T conocimos a James Ellroy, Andrew Vachss, Jerome Charyn y (disculpen si no es suficiente) los comienzos de Giancarlo De Cataldo y Pino Ca-cucci. Para el terror stricto sensu, se centraron en nombres desconocidos de extraordinaria clase como K.W. Jeter, Jack Curtis, Stephen Gallagher y (allá vamos) Robert McCammon. Un autor, como se ha escrito, natural de Ala-bama, uno de los favoritos de la casa Gargoyle y muy querido en Italia, que debutó con su décimo título, Mine. Si recordarlo hace justicia a Gri-maldi y Tropea (que tituló deliciosamente el libro en italiano Mary Terror, jugando con el nombre y apellido de la psicópata protagonista Mary Terrell), salta a la vista la paradoja selectiva -y angustiosa para tantos otros escritores anglosajones- que imponen las leyes del mercado, al menos aquí en Italia. Donde precisamente te pueden traducir y conocer tu décimo título. Interno Giallo no se limitó a Mine y propuso en el 92 Boy's Life, una extraordinaria respuesta, impregnada de amor por el cine y nostalgia, a Different Seasons de King, titulada The Belly of the Lake. Era el segundo libro de McCammon en Italia, el undécimo en América (donde se había publicado el año anterior), aparte de muchos relatos dispersos aquí y allá en diversas antologías.

Aunque la experiencia «en solitario» de Interno Giallo cesaría pronto, absorbida por Mondadori y transformada en serie, el paso de McCammon en Italia estaba por entonces bien asentado. Y, en evidente desorden cronológico, aparecieron en estrecha sucesión los siguientes títulos: Baal (su título de debut), el fluvial y apocalíptico Canto del Cisne (Tenebre) y luego, diluidos poco a poco, la ciencia-ficción Stinger (L'invasione), la acción «realista» Gone South (L'inferno nella palude) y Bethany's Sin (Loro attendono, un título tan paradigmático como siempre, dado que se publicó en Estados Unidos en 1980 y en Italia en el 96). Luego el silencio, un apagón que en realidad era un espejo perfecto de la «crisis de crecimiento» que golpeaba al otro lado.

Source images / Fuente imágenes: Robert McCammon.

Fuente de la imagen banner final post / Image source banner final post.