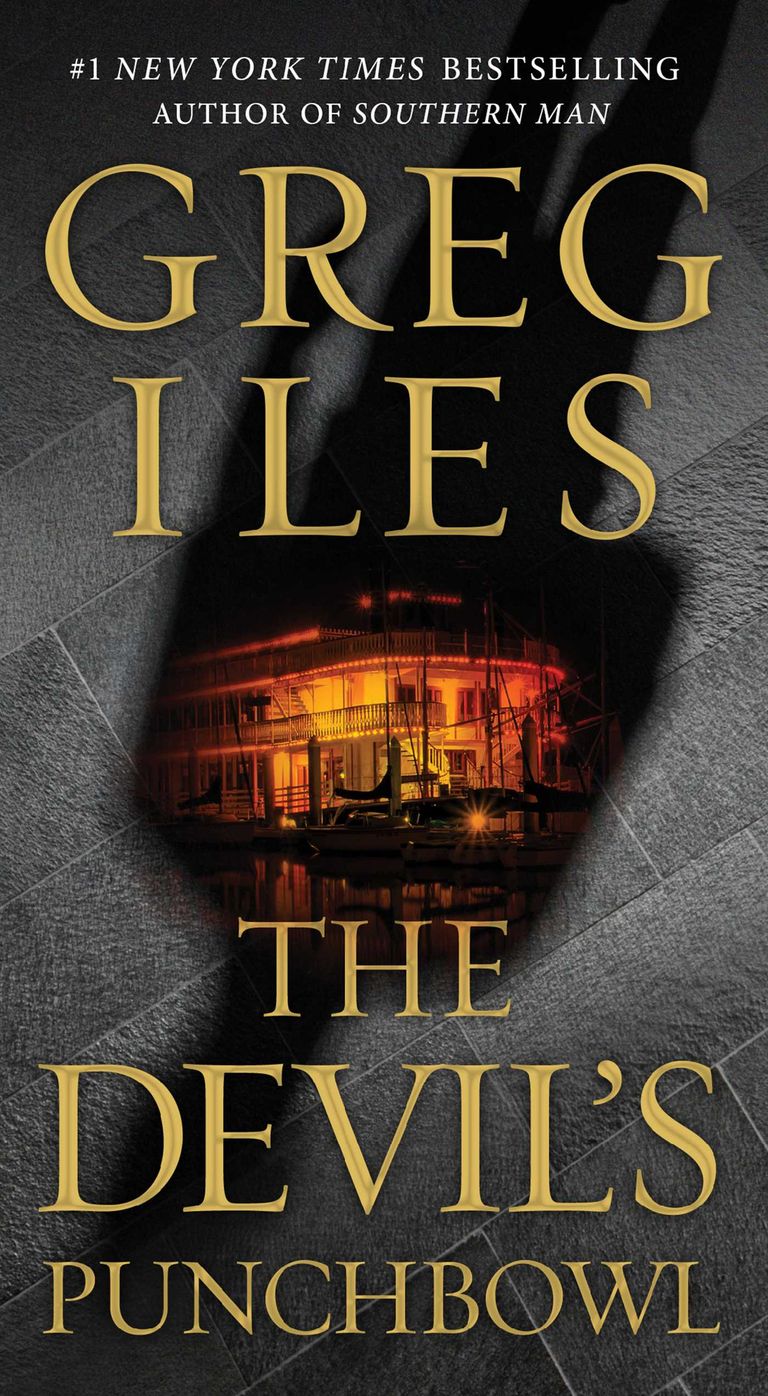

In the guise of district attorney, Penn Cage has had dozens of murderers sentenced to death row. He believed he had seen the worst, made the hardest choices. Never did he imagine he would face the greatest risk once elected mayor of his city.

For Natchez in the southern United States has all the air of a quiet place: a town rich in history but somewhat decadent, to which luster and prosperity should be restored, where the most tenacious problem seems to be latent racial tensions.

The truth is that Natchez hides its true face even from Cage. A face that reveals itself in the night, on the floating casinos moored on the banks of the Mississippi, which have multiplied since the temptation of easy money made gambling rampant. A face blacker than the worst expectations, if it is true that one of the casinos, the Magnolia Queen, is actually a den of prostitution and illegal dogfighting.

The tip comes to Cage from Tim Jessup, his old childhood friend, who now works at the Magnolia. Shortly after the confession, the man is found murdered, with a bullet in his chest and dog bites all over his body. Cage feels the weight of guilt, for failing to protect his friend, and the weight of failure, for failing to defend his town from the creep of evil. But the search for the culprits soon proves to be a lonely hunt: among the local authorities, in fact, no one is willing to help him...

Como fiscal del distrito, Penn Cage ha condenado a decenas de asesinos al corredor de la muerte. Creía haber visto lo peor, haber tomado las decisiones más difíciles. Nunca imaginó que se enfrentaría al mayor de los riesgos una vez elegido alcalde de su ciudad.

Porque Natchez, en el sur de Estados Unidos, tiene todo el aire de un lugar tranquilo: una ciudad rica en historia pero algo decadente, a la que habría que devolver el lustre y la prosperidad, donde el problema más tenaz parecen ser las tensiones raciales latentes.

Lo cierto es que Natchez oculta su verdadero rostro incluso a Cage. Un rostro que se revela en la noche, en los casinos flotantes amarrados a orillas del Mississippi, que se han multiplicado desde que la tentación del dinero fácil hizo estragos en el juego. Un rostro más negro que las peores expectativas, si es cierto que uno de los casinos, el Magnolia Queen, es en realidad un antro de prostitución y peleas ilegales de perros.

El chivatazo le llega a Cage de Tim Jessup, su viejo amigo de la infancia, que ahora trabaja en el Magnolia. Poco después de la confesión, el hombre aparece asesinado, con una bala en el pecho y mordeduras de perro por todo el cuerpo. Cage siente el peso de la culpa, por no haber protegido a su amigo, y el peso del fracaso, por no haber sabido defender a su ciudad de la peste del mal. Pero la búsqueda de los culpables pronto se revela como una caza solitaria: entre las autoridades locales, en efecto, nadie está dispuesto a ayudarle...

Midnight in the Garden of the Dead.

A silver moon, suspended above the black mirror of river waters, pours its icy light on the highway that winds from Louisiana to Texas.

I stand still here among the tombstones, shaken by a chill. I am the only human presence within miles. At my feet a simple slab of granite, beneath which lies the body of my wife.

Engraved on the tombstone are these words:

SARAH ELIZABETH CAGE

1963-1998

Beloved daughter, wife, mother, teacher

I did not sneak into the cemetery late at night to visit my wife's grave. I am here because a friend asked me to. And if I agreed, it was not out of friendship, but out of guilt. And out of fear.

The man I am waiting for is forty-five years old, but for me it is as if he is still nine. It was at that age that we met, at the time of the first moon landing. Friendships born in childhood create bonds that last. My sense of guilt is the same as that of seeing someone being lost without being able to do anything to save them. Over the years, Tim Jessup has continued to get into trouble, and I, after a few initial attempts, stopped helping him.

As for fear, it has nothing to do with Tim. He is just a messenger: he will come to bring me news that I would rather not receive. News that might confirm the gossip whispered on golf courses, murmured in hunting lodges, whispered on the sidelines during football games, like a wind rising before a storm.

When Tim asked me to meet him, I hesitated. This is the worst time to come to terms with conscience, both for me and for the city. But in the end I agreed to listen to what he will have to say. Because if those rumors are true, if it is true that evil has entered Natchez, I was the one who opened the door for it. I ran for mayor believing all the way in my mission. Certain of my honesty, I was presumptuous enough to think that I could come to terms with the devil without soiling the conscience of this city. But it was only a pious illusion.

For months now, the sense of failure has been growing inside me, oppressing me with an unbearable weight. Rarely in my life have I failed, and I have never given myself away. All Americans are taught that one must not give up, but here in the South this precept is almost a religion. Two years ago I stood in this same place before my wife's grave, my heart filled with hope and the certainty that through my own good will I would turn around the fortunes of the charming town where I was born, closing the open wounds left by the racial question. Now, after two years, halfway through my term as mayor, I have realized that people do not like change, even if it is for their own good. We talk a lot about ideals, but our lives are governed only by opportunism and prejudice. Taking note of this hypocrisy was an experience that challenged me.

The people who love me knew right away how it was going to turn out. My father and my partner at the time tried to save me from my illusions, but I didn't listen to them. Worst of all, it was my daughter who paid the highest price. Two years ago I seemed to hear my wife's voice, encouraging me to keep going. Now I hear only the indistinct breath of the wind: repeating to me under my breath the lesson that so many have learned before me: "There is no turning back."

My watch reads half past midnight. Tim is half an hour late, and there is no sign of him in the forest of tombstones that lies between me and Cemetery Road. I greet my wife in silence, then make my way to the spot set for the meeting: the Hill of the Jews, the small rise that houses the Jewish section of the cemetery. My footsteps make no noise; the grass is moist, thick and well-manicured. Many of the names engraved on the headstones belong to people I have known. They are connected to my history, but also to the city's. Friedler, Jacobs and Dreyfus on Jewish Hill; Knoxe, Henry and Thornhill in the Protestant section, and finally Donnelly, Binelli and O'Banyon in the Catholic section. Most of the dead buried here were light-skinned. However, in the lots marked black on the cemetery map rest the few servants and the most faithful slaves who, living on the fringes of the white world, earned the right to a sod of consecrated ground. Mostly they were interred without headstones or other identifying marks. One must come down the hill and go to the National Cemetery to find the graves of free blacks: mostly soldiers, whose remains rest among those of the one hundred and twenty-eight unnamed Civil War dead. Yet the history of this place is even older. There are graves of people born in the mid-eighteenth century: if their occupants resurrected, they would find that some parts of the city have not changed much since their time. Children who died of yellow fever rest beside Spanish nobles and forgotten generals, all now decomposed under statues of "anti's and weeping angels. Natchez is the oldest city on the Mississippi River, older even than New Orleans: to understand this, one only has to look at the blackened, half-sunken tombstones in the ground that are lost all the way into the forest.

When Tim Jessup.rm called to ask me to meet him, I thought he wanted to meet me here for simple convenience. Tim works at the Magnolia Queen, one of the floating casinos moored along the riverbank. The Magnolia is located roughly below Jew's Hill, and Tim's shift ends right at midnight. He explained to me, however, that he chose the cemetery because it is a secluded spot and we are not in danger of being seen by anyone. He also warned me, saying that I should not trust anyone, not even the police department or city hall officials. Then he made me swear that I would not call him on his cell phone or home phone for any reason. At the moment his recommendations seemed excessive and a bit ridiculous, but then I had to agree with him: corruption can penetrate anywhere, I myself experienced it more than once.

In my previous life I was a lawman, working as a prosecutor for the Houston district attorney's office. I began my career as an idealistic lawyer à la Atticus Finch and ended it after sending sixteen people to death row. In retrospect, I can't say exactly what happened. The fact is that one morning I woke up and realized that punishing the guilty was not the purpose of my life. So I resigned and went home to my wife and daughter. Not knowing how to use the time I had at that point (and needing money), I began to write novels inspired by my experiences as a magistrate, following, like so many other former lawyers, the path laid out by John Grisham. My books had some success and my name ended up on the bestseller list. A

that point we bought a bigger house and enrolled Annie in a more prestigious school. I began to feel a new excitement: a sense of omnipotence, a certainty that whatever I undertook, I would be successful. I was so young and arrogant to think I had deserved everything I had, and so stupid to believe it would last forever.

Then my wife died.

We buried her four months after my father diagnosed her with cancer. The shock of her loss threatened to wipe out my life and that of my four-year-old daughter. Overcome with grief, I returned to Houston to pick up Annie and bring her back to the small Mississippi town where I grew up, entrusting her to the affection of my parents. And it was here in Natchez, while I was still trudging to make sense of my life again, that I became involved in a murder case: an affair dating back 30 years. That experience saved my life, but it cut short the lives of four people. Seven years have passed since then. Annie today is eleven years old and beautiful, the picture of her mother. Right now she is at home sleeping. I left her with the babysitter, who is waiting for my return. I decide to give Tim just five more minutes. What the heck. If he can't make it on time, he can always come find me in my office at City Hall, like they all do.

My heart is hammering in my chest: the climb to the top of Jew's Hill is steep as hell. With every breath, I get the heady scent of osmanthus bushes, still in bloom in mid-October. Beneath the effluvium of the flowers simmers a mixture of heavier smells: damp leaves, soil and something dead in the trees, perhaps a deer shot by a passing poacher.

As soon as I reach the top of the hill, the landscape and the loop suddenly open up before me, leaving me breathless.

The river flows sixty meters below. From this height one can see the immeasurable plain stretching as far as the eye can see to the west with a majesty that stuns. The feeling one gets is the same one that has prompted so many nations in the past to vie for these lands. France, Spain, England, the Confederate States during the War of Secession: all tried to take it over, never succeeding, as had happened to the Natchez Indians before them.

As I sit on a bench, I see two headlights come up Cemetery Road like a boat sailing against the wind, jerking on the narrow roadway that winds along the edge of the sheer escarpment over the river. I stand up, but the vehicle doesn't slow down, and after a few moments I can make out a pickup truck rattling past the shack on the other side of the road. Then it disappears after the first curve, in dircection of the Devil's Den, a deep gorge on the edge of the county where outlaws who once haunted the area dumped the corpses of their victims.

"I'm sorry Tim," I say out loud. "Time's up."

The wind blowing from the river gets stronger and penetrates under my jacket. I am cold, tired, and want to go to bed. I have three hectic days ahead of me, the busiest of the year for the mayor of Natchez. Tomorrow morning I have a press conference scheduled, then a helicopter flight over the city. But once I get through these three days, there will be big changes in my life.

I step away from the bench and walk toward the less steeply sloping front of the hill, heading for my old Saab parked beyond the cemetery wall. As I lean forward to face the descent, an apprehensive voice breaks the silence: "Hey, buddy. You there?"

A shadow, emerging from the innermost part of the cemetery, advances toward me. From here I can see all four entrances, but I didn't notice any headlights or hear a car engine. Here he is, Tim Jessup. He materializes as one of the ghosts that are said to haunt this ancient hillside. I recognize him right away, because Tim used to be a junkie and still moves like someone looking for a fix: that stiff, uncoordinated gait on thin legs, that constant looking around to make sure some cop doesn't jump out.

He swears he stopped using long ago, thanks in large part to Julia, his new wife, who is three years younger than us and went to the same school as us. When she was nineteen, Julia had married the quarterback of the school football team, and it took her five years of hell before she decided to divorce him. When I heard she was marrying Tim Jessup, I thought she was going to add another failure to her resume. But the word around town is that Julia worked wonders with Tim. She got him a job as a dealer at the blackjack tables in one of the floating casinos and managed to keep him from quitting. Tim has been in a straight line for more than a year now and was recently hired at the Magnolia Queen.

"Penn!" he calls me. "It's me. Where have you been? Come out!"

The moonlight highlights the thinness of his face. Although we are the same age-we were born only a month apart-Tim looks much older than me. His skin has the texture of leather, as happens to people who have been in the Mississippi sun too long. The nico-I lina makes his gray mustache yellowish; his skin and eyes have the jaundiced tinge of a man whose liver has reached the end of its rope.

One of the things that united us most as boys was the fact that we were both children of a doctor. We were all too aware of the responsibility that rested on our fathers, much like that of priests. Being sons of a ||nedical man can bring benefits but also disadvantages. They all ; expel that firstborns follow in their father's footsteps, llchoosing the same profession. In fact, Tim and I have both disappointed those expectations, albeit by very different paths.

With a sigh of resignation, I let him see me. "Tim? Hey, it's me."

He turns sharply and quickly slips his hand into his pocket as if to reach for something. For a moment I'm terrified he's about to pull out a gun, but then he recognizes me and relaxes.

"Dude," he says with a smirk. "I thought you stood me up."

"You're the one who was late."

He nods several times. He is one who can never sit still. I wonder how he can stay all night at the blackjack table.

"I couldn't leave too fast," he explains. "I think they're keeping an eye on me. Although in fact all Magnolia employees are constantly being watched. But maybe they have some specific suspicions about me."

"I didn't see your car. How did you get here?"

A sly smile illuminates his hollowed-out face for a moment. "I have my ways, man. You have to be careful with people like that. They're like predators, I tell you. As soon as they hear a threat, they snap and ... bam" He claps his hands. "They kill out of pure instinct, like sharks." He turns toward the city stretching out below us. "By the way, we'd better find a place less in sight." He leads me toward the small wall that borders a small plot of graves from the same family. "Just like in our school days. Do you remember when we used to come here to get high? We used to sit right back here so the cops wouldn't see the embers of the joint."

Actually, in my school days I never smoked pot with Tim, but I'd rather not contradict him. I hope he will quickly report what he has to tell me so I can go home.

Tim jumps to the other side with surprising agility. As I follow him, stepping over the small wall, I am reminded of the one memory of this cemetery that I associate with Tim. It was Halloween night. Together with other kids we threw our dirt bikes over the cemetery wall and began frolicking through the driveways and graves, laughing and having the time of our lives, until we were attacked by a pack of stray dogs. They chased us to the large oak trees that stand near one of the entrance gates. I wonder if Tim remembers that.

Casting a last, anxious glance in the direction of Cemetery Road, Tim sits on the wet ground, leaning his back against the moss-covered bricks. I sit beside him, the toe of my jogging shoes brushing against the toe of his battered boat shoes. He must have had time to change: he is not wearing a croupier's uniform, but a pair of black jeans and a gray T-shirt.

"You can't walk out of the Magnolia in your work uniform," he says, as if he has read my mind. Surely he has noticed that I am eyeing him suspiciously, studying him.

I decide to skip the pleasantries and get straight to the point. "The things you told me on the phone are disturbing, otherwise I wouldn't have come here at this time."

Tim nods as he pulls a half-folded cigarette from his pocket. "Better not light it, just in case," he says, putting it in his mouth. "I'll smoke it later on my way home." He still hints at a smirk, then turns serious. "So what did you know about this before I called you?"

"I only heard a few rumors. Important personalities coming to Natchez to gamble, staying in town the bare minimum, a one-night stand. Professional sportsmen, millionaire rappers, people like that. People who wouldn't normally come to these parts."

"Ever heard of dogfighting?"

I hoped at least that was just a rumor. "Yes, but I have some difficulty believing it. It's a country people thing. I know they sometimes hold these fights in rural communities across the river. But it's not the kind of show that attracts VIPs and rich people."

Tim bites his lower lip. "What else do you know?"

I'm not going to respond this time. I have heard other things-for example, that in the gambling environment prostitution and hard drug dealing also thrive-but these are problems that have always been there in our community. "I don't feel like drawing conclusions based on rumors that might turn out to be false."

"Hey, man, did you notice that? You sound just like a fucking politician."

That's exactly what I am, although right now I feel more like a lawyer trying to figure out how much truth there is in the story an untrustworthy client is telling him. "You tell me what you know, and then we'll see if it matches up with what I know."

Tim becomes increasingly agitated and finally gives in to the need for nicotine. He pulls out a lighter, places the tip of the cigarette near the flame and lights it. "Do you know I've become a daddy? I have a beautiful baby boy," he says blowing out the smoke.

"Yes, I saw him with Julia. We met at the supermarket two weeks ago. He's such a beautiful baby boy."

A smile lights up his face. "He looks like his mother. Julia is still a beautiful girl, you've seen her too."

"Yes, of course." I agree, but I am impatient. "So Tim, what are we going to do? Why did you want to meet me?"

He doesn't answer. He takes another puff, holding the cigarette between his thumb and forefinger, tucked in his palm as if it were a joint. I see that he is shivering, and it is not from the cold. His whole body has begun to quiver, and I get the suspicion that he has started using drugs again.

"Tim?"

"It's not what you think, man. The thing is, this has been nagging at me for a while. Sometimes thinking about it gives me the creeps."

I realize he is crying, and I am taken aback. As he wipes his eyes, I put my hand on his knee to reassure him. "Is everything all right?" I ask him.

He puts out his cigarette on a tombstone and leans forward. In his gaze burns a light I thought extinguished forever. "I can tell you everything, but remember there's no going back later. And stuff that won't let you sleep at night. I know you: you're like a pit bull and you won't be able to let go."

"And that's why you asked me to come here tonight, right?"

He clutches his shoulders as his head and hands begin to shake again. "I'm telling you for the last time, Penn. If this doesn't interest you, leave now. Climb over that little wall and go back to your car. That's what any person with half a brain would do."

I lean my back against the cold bricks, trying to think. It is the oldest dilemma in the world: "Is blissful ignorance or uncomfortable awareness better?" I ; seem to see Tim behind his blackjack table: ; "Card or lay, sir?" I actually have no choice, because j too helped bring the Magnolia to Natchez.

"Come on, Tim, tell me all about it. We can't be here 6 all night."

He stares at me for a long time, then turns on his side and pulls out something from the back pocket of his jeans. At first glance they look like playing cards. He hands them to me, holding them under his upturned palm, as if trying to hide them.

"Should I pick a card?" I ask him. "They are not cards. They are photographs. A little blurry, pearls were taken with a cell phone." I reach out my hand and take them. I've seen thousands of photos taken at crime scenes, detailed and rebooted images, and I think I'm prepared. But as soon as Tim clicks the lighter and with the flame illuminates the first photo, I feel my stomach turn.

"I know," Tim says in a tired voice. "And you still don't know the rest."

Medianoche en el Jardín de los Muertos.

Una luna plateada, suspendida sobre el espejo negro de las aguas del río, derrama su luz helada sobre la carretera que serpentea de Luisiana a Texas.

Permanezco inmóvil aquí, entre las lápidas, sacudido por un escalofrío. Soy la única presencia humana en kilómetros a la redonda. A mis pies una simple losa de granito, bajo la cual yace el cuerpo de mi esposa.

Grabadas en la lápida están estas palabras:

SARAH ELIZABETH CAGE

1963-1998

Amada hija, esposa, madre, maestra

No me he colado en el cementerio a altas horas de la noche para visitar la tumba de mi esposa. Estoy aquí porque un amigo me lo pidió. Y si accedí, no fue por amistad, sino por culpa. Y por miedo.

El hombre al que espero tiene cuarenta y cinco años, pero para mí es como si aún tuviera nueve. A esa edad nos conocimos, en el momento del primer alunizaje. Las amistades que nacen en la infancia crean lazos que perduran. Mi sentimiento de culpa es el mismo que el de ver a alguien perderse sin poder hacer nada por salvarlo. Con los años, Tim Jessup ha seguido metiéndose en líos, y yo, tras unos primeros intentos, dejé de ayudarle.

En cuanto al miedo, no tiene nada que ver con Tim. No es más que un mensajero: vendrá a traerme noticias que preferiría no recibir. Noticias que podrían confirmar los cotilleos susurrados en los campos de golf, murmurados en los pabellones de caza, susurrados en las bandas durante los partidos de fútbol, como un viento que se levanta antes de una tormenta.

Cuando Tim me pidió que nos viéramos, dudé. Este es el peor momento para asumir la conciencia, tanto para mí como para la ciudad. Pero al final accedí a escuchar lo que tuviera que decir. Porque si esos rumores son ciertos, si es verdad que el mal ha entrado en Natchez, fui yo quien le abrió la puerta. Me presenté a alcalde creyendo hasta el final en mi misión. Seguro de mi honradez, fui lo bastante presuntuoso como para pensar que podría llegar a un acuerdo con el diablo sin ensuciar la conciencia de esta ciudad. Pero no era más que una piadosa ilusión.

Desde hace meses, la sensación de fracaso crece en mi interior, oprimiéndome con un peso insoportable. Pocas veces en mi vida he fracasado, y nunca me he delatado. A todos los estadounidenses se les enseña que no hay que rendirse, pero aquí en el Sur este precepto es casi una religión. Hace dos años estaba en este mismo lugar, ante la tumba de mi esposa, con el corazón henchido de esperanza y la certeza de que con mi buena voluntad cambiaría la suerte de la encantadora ciudad en la que nací, cerrando las heridas abiertas por la cuestión racial. Ahora, después de dos años, a mitad de mi mandato como alcalde, me he dado cuenta de que a la gente no le gusta el cambio, aunque sea por su propio bien. Hablamos mucho de ideales, pero nuestras vidas sólo se rigen por el oportunismo y los prejuicios. Tomar nota de esta hipocresía fue una experiencia que me desafió.

Las personas que me quieren supieron enseguida cómo iba a acabar. Mi padre y mi pareja de entonces intentaron salvarme de mis ilusiones, pero no les hice caso. Lo peor de todo es que fue mi hija quien pagó el precio más alto. Hace dos años me parecía oír la voz de mi mujer, que me animaba a seguir adelante. Ahora sólo oigo el aliento indistinto del viento: repitiéndome en voz baja la lección que tantos han aprendido antes que yo: "No hay vuelta atrás".

Mi reloj marca las doce y media de la noche. Tim lleva media hora de retraso y no hay rastro de él en el bosque de lápidas que se extiende entre mí y Cemetery Road. Saludo a mi mujer en silencio y me dirijo al lugar fijado para la reunión: la Colina de los Judíos, la pequeña elevación que alberga la sección judía del cementerio. Mis pasos no hacen ruido; la hierba está húmeda, espesa y bien cuidada. Muchos de los nombres grabados en las lápidas pertenecen a personas que he conocido. Están relacionados con mi historia, pero también con la de la ciudad. Friedler, Jacobs y Dreyfus en la colina judía; Knoxe, Henry y Thornhill en la sección protestante, y finalmente Donnelly, Binelli y O'Banyon en la sección católica. La mayoría de los muertos enterrados aquí eran de piel clara. Sin embargo, en los lotes marcados en negro en el plano del cementerio descansan los pocos sirvientes y los esclavos más fieles que, viviendo al margen del mundo blanco, se ganaron el derecho a un terrón de tierra consagrada. La mayoría fueron enterrados sin lápidas ni otras marcas identificativas. Hay que bajar la colina e ir al Cementerio Nacional para encontrar las tumbas de los negros libres: en su mayoría soldados, cuyos restos descansan entre los de los ciento veintiocho muertos sin nombre de la Guerra Civil. Sin embargo, la historia de este lugar es aún más antigua. Hay tumbas de personas nacidas a mediados del siglo XVIII: si sus ocupantes resucitaran, descubrirían que algunas partes de la ciudad no han cambiado mucho desde su época. Niños que murieron de fiebre amarilla descansan junto a nobles españoles y generales olvidados, todos ellos ahora descompuestos bajo estatuas de "anti y ángeles llorones". Natchez es la ciudad más antigua del río Misisipi, más antigua incluso que Nueva Orleans: para entenderlo, basta con mirar las lápidas ennegrecidas y medio hundidas en el suelo que se pierden hasta el bosque.

Cuando Tim Jessup.rm me llamó para pedirme una cita, pensé que quería reunirse conmigo aquí por simple comodidad. Tim trabaja en el Magnolia Queen, uno de los casinos flotantes amarrados a la orilla del río. El Magnolia está situado más o menos debajo de Jew's Hill, y el turno de Tim termina justo a medianoche. Sin embargo, me explica que ha elegido el cementerio porque es un lugar apartado y no corremos peligro de que nos vea nadie. También me advirtió que no me fiara de nadie, ni siquiera de la policía o de los funcionarios del ayuntamiento. Luego me hizo jurar que no le llamaría al móvil ni al teléfono de casa por ningún motivo. En ese momento sus recomendaciones me parecieron excesivas y un poco ridículas, pero luego tuve que darle la razón: la corrupción puede penetrar en cualquier parte, yo mismo la experimenté más de una vez.

En mi vida anterior era un hombre de leyes, trabajaba como fiscal para la oficina del fiscal del distrito de Houston. Empecé mi carrera como un abogado idealista a lo Atticus Finch y la terminé tras enviar a dieciséis personas al corredor de la muerte. En retrospectiva, no puedo decir exactamente qué pasó. El hecho es que una mañana me desperté y me di cuenta de que castigar a los culpables no era el propósito de mi vida. Así que dimití y me fui a casa con mi mujer y mi hija. Como no sabía en qué emplear el tiempo que tenía en ese momento (y necesitaba dinero), empecé a escribir novelas inspiradas en mis experiencias como magistrado, siguiendo, como tantos otros antiguos abogados, el camino trazado por John Grisham. Mis libros tuvieron cierto éxito y mi nombre acabó en la lista de los más vendidos. Aese punto compramos una casa más grande y matriculamos a Annie en un colegio más prestigioso. Empecé a sentir una nueva excitación: una sensación de omnipotencia, la certeza de que, emprendiera lo que emprendiera, tendría éxito. Era tan joven y arrogante que pensaba que me había merecido todo lo que tenía, y tan estúpido que creía que duraría para siempre.

Entonces murió mi mujer.

La enterramos cuatro meses después de que mi padre le diagnosticara un cáncer. La conmoción de su pérdida amenazó con acabar con mi vida y con la de mi hija de cuatro años. Abrumado por el dolor, regresé a Houston para recoger a Annie y traerla de vuelta al pequeño pueblo de Mississippi donde crecí, confiándola al cariño de mis padres. Y fue aquí, en Natchez, mientras aún me esforzaba por volver a encontrarle sentido a mi vida, donde me vi envuelta en un caso de asesinato: una aventura que se remontaba a 30 años atrás. Aquella experiencia me salvó la vida, pero truncó la de cuatro personas. Han pasado siete años desde entonces. Annie tiene hoy once años y es preciosa, la viva imagen de su madre. Ahora mismo está en casa durmiendo. La he dejado con la niñera, que espera mi regreso. Decido darle a Tim sólo cinco minutos más. Qué más da. Si no puede llegar a tiempo, siempre puede venir a buscarme a mi despacho del Ayuntamiento, como hacen todos.

El corazón me martillea en el pecho: la subida a la cima de Jew's Hill es muy empinada. Cada vez que respiro, me llega el embriagador aroma de los arbustos de osmanthus, aún en flor a mediados de octubre. Bajo el efluvio de las flores hierve a fuego lento una mezcla de olores más pesados: hojas húmedas, tierra y algo muerto entre los árboles, quizá un ciervo abatido por un cazador furtivo que pasaba por allí.

En cuanto llego a la cima de la colina, el paisaje y el bucle se abren de repente ante mí, dejándome sin aliento.

El río fluye sesenta metros más abajo. Desde esta altura se divisa la inconmensurable llanura que se extiende hasta donde alcanza la vista hacia el oeste con una majestuosidad que aturde. La sensación que se tiene es la misma que ha impulsado a tantas naciones en el pasado a disputarse estas tierras. Francia, España, Inglaterra, los Estados Confederados durante la Guerra de Secesión: todos intentaron apoderarse de ellas, sin conseguirlo nunca, como les había ocurrido antes a los indios natchez.

Sentado en un banco, veo dos faros que suben por Cemetery Road como un barco que navega contra el viento, sacudiéndose en la estrecha calzada que serpentea por el borde de la escarpada escarpadura sobre el río. Me paro, pero el vehículo no aminora la marcha y, al cabo de unos instantes, distingo una camioneta que pasa traqueteando junto a la choza, al otro lado de la carretera. Luego desaparece tras la primera curva, en dirección a la Guarida del Diablo, un profundo desfiladero en los límites del condado donde los forajidos que antaño rondaban la zona arrojaban los cadáveres de sus víctimas.

"Lo siento, Tim", digo en voz alta. "Se acabó el tiempo".

El viento que sopla desde el río se hace más fuerte y penetra bajo mi chaqueta. Tengo frío, estoy cansado y quiero irme a la cama. Me esperan tres días frenéticos, los más ajetreados del año para el alcalde de Natchez. Mañana por la mañana tengo programada una rueda de prensa y luego un vuelo en helicóptero sobre la ciudad. Pero una vez que pase estos tres días, habrá grandes cambios en mi vida.

Me alejo del banco y camino hacia la parte delantera de la colina, menos inclinada, en dirección a mi viejo Saab aparcado más allá de la tapia del cementerio. Cuando me inclino para afrontar el descenso, una voz aprensiva rompe el silencio: "Hola, colega. ¿Estás ahí?"

Una sombra, que emerge de lo más recóndito del cementerio, avanza hacia mí. Desde aquí puedo ver las cuatro entradas, pero no he visto ningún faro ni he oído el motor de un coche. Aquí está, Tim Jessup. Se materializa como uno de los fantasmas que se dice que rondan esta antigua ladera. Lo reconozco enseguida, porque Tim fue yonqui y aún se mueve como alguien que busca una dosis: ese andar rígido y descoordinado sobre piernas delgadas, esa mirada constante a su alrededor para asegurarse de que no salta algún policía.

Jura que dejó de consumir hace tiempo, en gran parte gracias a Julia, su nueva esposa, que es tres años más joven que nosotros y fue al mismo colegio que nosotros. A los diecinueve años, Julia se había casado con el quarterback del equipo de fútbol del colegio, y le costó cinco años de infierno antes de decidirse a divorciarse de él. Cuando me enteré de que se casaba con Tim Jessup, pensé que iba a añadir otro fracaso a su currículum. Pero en la ciudad se dice que Julia hizo maravillas con Tim. Le consiguió un trabajo como crupier en las mesas de blackjack de uno de los casinos flotantes y consiguió que no lo dejara. Tim lleva más de un año en línea recta y hace poco le contrataron en el Magnolia Queen.

"¡Penn!", me llama. "Soy yo. ¿Dónde has estado? ¡Sal!"

La luz de la luna resalta la delgadez de su rostro. Aunque tenemos la misma edad -nacimos con sólo un mes de diferencia-, Tim parece mucho mayor que yo. Su piel tiene la textura del cuero, como les ocurre a las personas que llevan demasiado tiempo bajo el sol del Misisipi. La nicotina amarillea su bigote canoso; su piel y sus ojos tienen el tinte ictérico de un hombre cuyo hígado ha llegado al final de su cuerda.

Una de las cosas que más nos unía como muchachos era el hecho de que ambos éramos hijos de un médico. Éramos muy conscientes de la responsabilidad que recaía sobre nuestros padres, muy parecida a la de los sacerdotes. Ser hijos de un médico puede traer beneficios, pero también desventajas. Todos ; expulsan que los primogénitos sigan los pasos de su padre, llcogiendo la misma profesión. De hecho, tanto Tim como yo hemos defraudado esas expectativas, aunque por caminos muy diferentes.

Con un suspiro de resignación, dejo que me vea. "¿Tim? Hola, soy yo".

Se gira bruscamente y se lleva rápidamente la mano al bolsillo, como si fuera a coger algo. Por un momento me aterra que esté a punto de sacar una pistola, pero entonces me reconoce y se relaja.

"Tío", dice sonriendo. "Creía que me habías dejado plantado".

"Tú eres el que llegó tarde".

Asiente varias veces. Es de los que nunca pueden estarse quietos. Me pregunto cómo puede estar toda la noche en la mesa de blackjack.

"No podía irme demasiado rápido", explica. Creo que no me quitan ojo de encima". Aunque en realidad todos los empleados de Magnolia están constantemente vigilados. Pero quizá tengan sospechas concretas sobre mí".

"No vi tu coche. ¿Cómo has llegado hasta aquí?"

Una sonrisa socarrona ilumina por un momento su rostro ahuecado. "Tengo mis maneras, tío. Hay que tener cuidado con gente así. Son como depredadores, te lo aseguro. En cuanto oyen una amenaza, se espabilan y... ¡bam!" Da una palmada. "Matan por puro instinto, como los tiburones". Se vuelve hacia la ciudad que se extiende bajo nosotros. "Por cierto, será mejor que encontremos un lugar menos a la vista". Me conduce hacia el pequeño muro que bordea una pequeña parcela de tumbas de la misma familia. "Como en nuestros días de colegio. ¿Recuerdas cuando veníamos aquí a drogarnos? Nos sentábamos aquí detrás para que los polis no vieran las brasas del porro".

En realidad, en mis tiempos de colegio nunca fumé porros con Tim, pero prefiero no llevarle la contraria. Espero que me informe rápidamente de lo que tiene que decirme para poder irme a casa.

Tim salta al otro lado con sorprendente agilidad. Mientras le sigo, saltando el pequeño muro, me viene a la memoria el único recuerdo de este cementerio que asocio con Tim. Era la noche de Halloween. Junto con otros niños tiramos nuestras motos de cross por encima del muro del cementerio y empezamos a retozar por los caminos y las tumbas, riendo y pasándolo como nunca, hasta que nos atacó una jauría de perros callejeros. Nos persiguieron hasta los grandes robles que hay cerca de una de las puertas de entrada. Me pregunto si Tim se acuerda de aquello.

Tim lanza una última y ansiosa mirada en dirección a Cemetery Road y se sienta en el suelo mojado, apoyando la espalda en los ladrillos cubiertos de musgo. Me siento a su lado, con la punta de mis zapatillas de correr rozando la de sus maltrechos náuticos. Debe de haber tenido tiempo de cambiarse: no lleva el uniforme de crupier, sino unos vaqueros negros y una camiseta gris.

"No puedes salir del Magnolia con tu uniforme de trabajo", dice, como si me hubiera leído el pensamiento. Seguro que se ha dado cuenta de que le miro con desconfianza, estudiándole.

Decido saltarme las galanterías e ir directamente al grano. "Las cosas que me contaste por teléfono son inquietantes, de lo contrario no habría venido aquí a estas horas".

Tim asiente mientras saca un cigarrillo a medio doblar del bolsillo. "Mejor no lo enciendo, por si acaso", dice, llevándoselo a la boca. "Me lo fumaré más tarde de camino a casa". Todavía insinúa una sonrisa burlona, luego se pone serio. "¿Qué sabías de esto antes de que te llamara?

"Sólo oí algunos rumores. Personalidades importantes que venían a Natchez a apostar, se quedaban en la ciudad lo mínimo, un rollo de una noche. Deportistas profesionales, raperos millonarios, gente así. Gente que normalmente no vendría por estos lares".

"¿Has oído hablar de las peleas de perros?"

Esperaba que al menos fuera sólo un rumor. "Sí, pero me cuesta creerlo. Es cosa de la gente del campo. Sé que a veces celebran estas peleas en comunidades rurales al otro lado del río. Pero no es el tipo de espectáculo que atrae a VIPs y gente rica".

Tim se muerde el labio inferior. "¿Qué más sabes?".

Esta vez no voy a responder. He oído otras cosas -por ejemplo, que en el ambiente del juego también prosperan la prostitución y el tráfico de drogas duras-, pero son problemas que siempre han estado ahí en nuestra comunidad. "No me apetece sacar conclusiones basadas en rumores que pueden resultar falsos."

"Oye, tío, ¿te has dado cuenta? Suenas como un puto político".

Eso es exactamente lo que soy, aunque ahora mismo me siento más como un abogado tratando de averiguar cuánto hay de verdad en la historia que le está contando un cliente poco fiable. "Dime lo que sabes y luego veremos si coincide con lo que yo sé".

Tim se agita cada vez más y finalmente cede a la necesidad de nicotina. Saca un mechero, coloca la punta del cigarrillo cerca de la llama y lo enciende. "¿Sabes que he sido papá? Tengo un niño precioso", dice expulsando el humo.

"Sí, lo he visto con Julia. Nos conocimos en el supermercado hace dos semanas. Es un niño precioso".

Una sonrisa ilumina su rostro. "Se parece a su madre. Julia sigue siendo una niña preciosa, tú también la has visto".

"Sí, claro". Estoy de acuerdo, pero estoy impaciente. "Entonces Tim, ¿qué vamos a hacer? ¿Por qué querías quedar conmigo?"

No contesta. Da otra calada, sosteniendo el cigarrillo entre el pulgar y el índice, metido en la palma de la mano como si fuera un porro. Veo que tiembla, y no de frío. Todo su cuerpo ha empezado a temblar, y tengo la sospecha de que ha vuelto a consumir drogas.

"¿Tim?"

"No es lo que piensas, tío. Lo que pasa es que esto me ha estado dando la lata durante un tiempo. A veces pensar en ello me da escalofríos".

Me doy cuenta de que está llorando y me sorprende. Mientras se limpia los ojos, le pongo la mano en la rodilla para tranquilizarle. "¿Va todo bien?" le pregunto.

Apaga el cigarrillo sobre una lápida y se inclina hacia delante. En su mirada arde una luz que creí extinguida para siempre. "Puedo contártelo todo, pero recuerda que luego no hay vuelta atrás. Y cosas que no te dejarán dormir por la noche. Te conozco: eres como un pitbull y no podrás soltarte".

"Y por eso me pediste que viniera esta noche, ¿verdad?".

Se aprieta los hombros mientras su cabeza y sus manos empiezan a temblar de nuevo. "Te lo digo por última vez, Penn. Si esto no te interesa, vete ahora. Salte ese pequeño muro y vuelva a su coche. Eso es lo que haría cualquier persona con medio cerebro".

Apoyo la espalda contra los fríos ladrillos, intentando pensar. Es el dilema más viejo del mundo: "¿Es mejor la dichosa ignorancia o la incómoda conciencia?". Me ; parece ver a Tim detrás de su mesa de blackjack: ; "¿Carta o lay, señor?". En realidad no tengo elección, porque yo también ayudé a traer el Magnolia a Natchez.

"Vamos, Tim, cuéntamelo todo. No podemos estar aquí 6 toda la noche".

Me mira fijamente durante un buen rato, luego se pone de lado y saca algo del bolsillo trasero de sus vaqueros. A primera vista parecen naipes. Me las da, sosteniéndolas bajo la palma de la mano, como si intentara ocultarlas.

"¿Elijo una carta?" le pregunto. "No son cartas. Son fotografías. Un poco borrosas, se tomaron con un móvil". Alargo la mano y las cojo. He visto miles de fotos tomadas en escenas del crimen, imágenes detalladas y reiniciadas, y creo que estoy preparada. Pero en cuanto Tim enciende el mechero y con la llama ilumina la primera foto, siento que se me revuelve el estómago.

"Lo sé", dice Tim con voz cansada. "Y aún no sabes el resto".

Source images / Fuente imágenes: Greg Iles.

Source final image / Fuente imagen final: Planeta de Libros.

Fuente de la imagen banner final post / Image source banner final post.

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks!

Telegram and Whatsapp

Thank you for supporting my content @blurtconnect-ng.