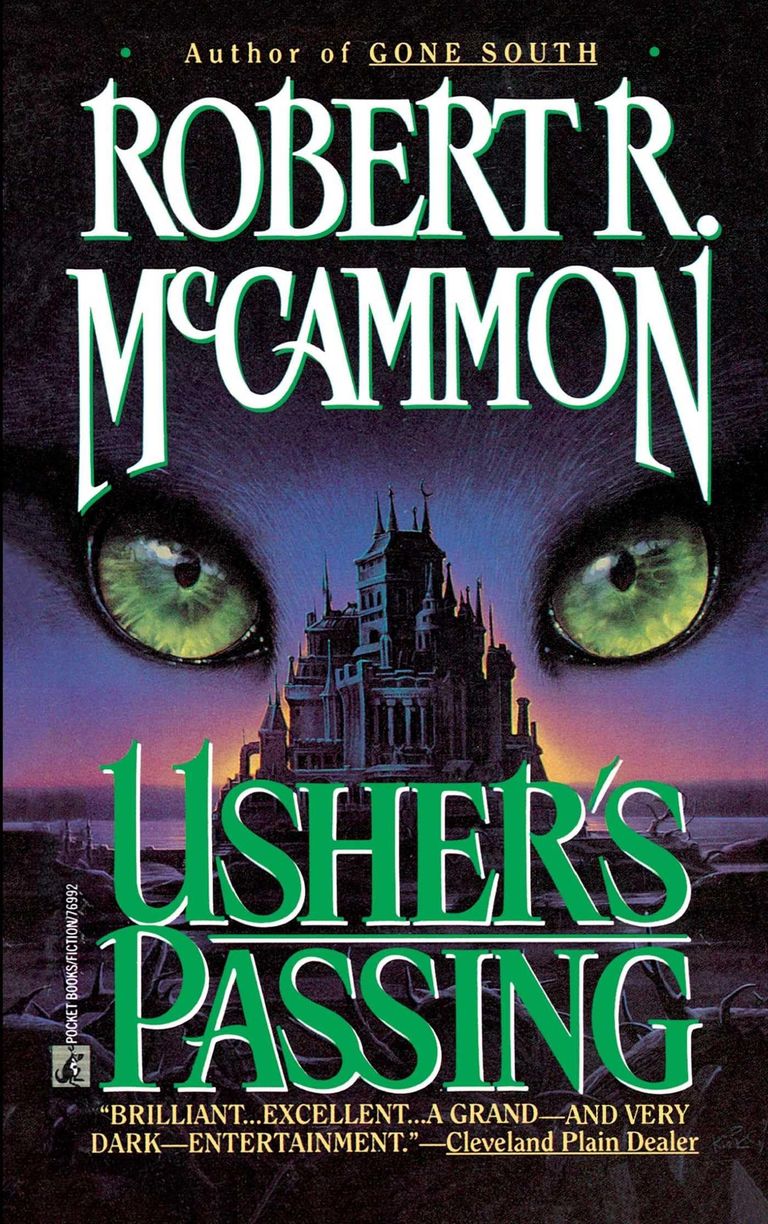

Ambientada en la actual Carolina del Norte, "La maldición de Usher" comienza con el regreso a casa de Rix, un escritor fallido con un matrimonio que terminó en tragedia. Lo espera su padre en su lecho de muerte.

Rix es un pacifista convencido y no tiene intención de hacerse cargo del negocio de 10 mil millones de dólares al que está predestinado. Pero la Casa lo ha elegido: él heredará las riendas, no sólo en lo que respecta a la opulenta herencia, que se dice que está maldita, sino también a los horripilantes y terribles secretos que habitan y gobiernan la Casa Usher. )

El trueno resonó como una campana de hierro sobre la ciudad de Nueva York, víctima ahora de una política salvaje de expansión urbana. En el aire pesado, los relámpagos crepitaron y tronaron hacia el suelo, estrellándose contra el campanario gótico de la nueva Grace Church de James Renwick, en East Tenth Street, e incinerando a un caballo de tiro medio ciego que caminaba penosamente por la explanada de los ocupas, al norte de 14th Street. El dueño del animal gritó aterrorizado e intentó salvarse saltando del carro que volcaba, hundiendo su carga de patatas en veinte centímetros de barro.

Era el 22 de marzo de 1847 y el hombre del tiempo del New York Tribune había pronosticado una noche de «espantosas tormentas eléctricas, absolutamente prohibitivas tanto para el hombre como para la bestia». Por una vez, su predicción había sido acertada. Las chispas estallaron en el cielo de Market Street, donde la chimenea de hierro fundido de una ferretería había sido electrocutada por un rayo. El edificio revestido de listones de madera ardía violentamente, mientras una multitud contemplaba el fuego con la boca abierta y esbozaba amplias sonrisas ante su brillante calor. Los carros de bomberos con sus mangueras se retrasaban mientras las ruedas de madera y los cascos de los caballos se enfangaban en el aguanieve del Bowery. Jaurías de perros, ratas y cerdos huían por los callejones, donde bandas como los Dover Boys, los Plug Uglies y los Moan Stickers acechaban a sus víctimas por los adoquines de las estrechas calles. A los policías les importaba más su pellejo que su deber, y por eso permanecían a buen recaudo, apostados bajo las lámparas de gas como otras tantas estatuas...

Nueva York era una ciudad joven, pero ya en plena decadencia. Ofrecía un espectáculo violento, lleno de peligros -las porras de los matones, para empezar-, pero también de oportunidades, como un monedero rebosante de monedas de oro. La confusión recorría las calles desde los muelles hasta los teatros, desde los salones de baile hasta los burdeles, desde Murder Bend hasta el Ayuntamiento con la misma imparcialidad, aunque algunas avenidas fueran intransitables debido a los pantanos de escombros y basura.

Los truenos volvieron a sonar y el cielo perturbado se abrió en un torrente. Empapó a damiselas y doncellas que salían por las puertas del restaurante Delmonico3, se estrelló contra las altas ventanas sobre Colonnade Row e hizo gotear el negro hollín de los tejados de las chabolas de los okupas. La lluvia apagó los incendios, interrumpió las reyertas, alentó las proposiciones indecentes o los asaltos asesinos y despejó las calles en una lenta corriente de inmundicia que se dirigía hacia el río. Al menos durante ese breve intervalo, se detuvo el marasmo humano de la noche.

Dos caballos saurios de Berbería arrastraban un landó negro por la avenida Broadway, en dirección sur hacia el puerto, con las cabezas inclinadas bajo el aguacero. El cochero irlandés estaba acurrucado dentro de su empapado abrigo marrón; vio el agua que goteaba del ala de su sombrero bajado y maldijo la decisión que había tomado aquella tarde de aparcar cerca del Hotel De Geyser, en Canal Street. Abatido, pensó que si no hubiera recogido a aquel pasajero, estaría en casa calentándose los pies frente al fuego con un buen vaso de cerveza negra al lado. Al menos tenía un águila real en el bolsillo... pero ¿de qué le serviría si moría de pulmonía? Blandió su látigo, asestando un débil golpe en el flanco de uno de los caballos, aunque sabía que no irían más rápido. Maldita sea, pensó. ¿Qué buscaba ese pasajero?

El caballero había embarcado frente a De Peyser, había puesto un águila dorada en la mano del cochero y le había dicho que condujera lo más rápidamente posible hasta la oficina del Tribune. Habiéndole ordenado que se quedara a esperarle, el cochero había dejado descansar a los caballos hasta que el hombre de negro reapareció un cuarto de hora más tarde y le asignó un nuevo destino. Fue un largo paseo por el campo, hasta un lugar en los alrededores de Fordham, a la sombra de las colinas de Long Island, mientras las nubes de tormenta teñidas de púrpura empezaban a espesarse y los truenos resonaban en la distancia. Al llegar a una pequeña casa de campo de aspecto cochambroso, una mujer oronda y de mediana edad, con el pelo cano y los ojos sobresaltados, había saludado al caballero... de muy mala gana, según había visto el cochero. Después de otra media hora en la que un aguacero de lluvia helada había dejado al cochero en peligro de tener que recurrir al bálsamo tibio y a fregar con aceite de gaulteria, el pasajero vestido de negro había reaparecido con una nueva serie de instrucciones: volver a Nueva York lo antes posible, para poder pasar por un montón de tabernas baratas en la parte más baja de la ciudad. ¡El Triángulo hacia el sur! Y por la noche! pensó el cochero sombríamente. El caballero tenía en mente una fulana barata, o un encuentro con la muerte.

A medida que avanzaban hacia el sur por calles donde no imperaba la ley, el cochero se sintió aliviado al ver que la lluvia torrencial mantenía a la mayoría de los delincuentes en sus casas. Alabados sean los santos! pensó... y en ese momento dos jóvenes harapientos salieron corriendo de un callejón en dirección al carruaje. El cochero vio con horror que uno de ellos llevaba un ladrillo en la mano, probablemente con la intención de romper los radios de una rueda... la mejor manera de golpearle y robarle tanto a él como al pasajero. Agitó su látigo salvajemente, gritando: «¡Adelante! Adelante!», y la cabalgata de caballos, presintiendo el peligro inminente, galopó sobre las resbaladizas piedras. El ladrillo salió despedido, pero acabó contra un lateral del carruaje, astillando su madera con un seco estrépito. «¡Adelante!», volvió a gritar el cochero, manteniendo los caballos a paso ligero hasta dejar atrás a los gamberros.

El tabique corredizo situado detrás de la caja del cochero se abrió. «Cochero», preguntó el pasajero, «¿qué ha sido eso?». Su voz era tranquila y firme: está acostumbrado a dar órdenes, pensó el hombre.

«Disculpe, señor, pero...». Miró por encima del hombro a través del tabique y vio a la pálida luz de la lámpara interior el rostro pálido y demacrado del cliente, caracterizado por una barba y un bigote plateados y bien cuidados. Los ojos del caballero estaban hundidos y brillaban del color del estaño bruñido, fijos en el cochero con aquella típica mirada aristocrática. El caballero tenía un aspecto extrañamente avejentado, el rostro libre de arrugas delatoras, la carne blanca como el mármol. Llevaba un traje negro y un brillante sombrero de copa; sus manos de dedos afilados, envueltas en guantes de cuero negro, jugueteaban con un bastón de marfil cuya empuñadura estaba formada por una magnífica cabeza plateada de felino -un león, había reconocido el cochero- con brillantes ojos de esmeralda.

«¿Pero qué?», preguntó el hombre. El cochero no pudo reconocer el acento.

Señor... no es muy seguro conducir por aquí. Usted parece un caballero refinado y respetable, y no se encuentran muchos de ellos en esta zona del...»

«Preocúpate sólo de conducir», le advirtió el hombre. «Pierdes el tiempo». Cerró la mampara corredera.

El cochero refunfuñó, con la barba empapada de lluvia, e instó a los caballos a seguir adelante. Un águila real no puede inducir a un hombre a hacer nada!, pensó. Pero al menos le haría pasar un buen rato en el bar.

«Sandy the Welshman's Cellar», un bar de Ann Street, fue la primera parada. El caballero entró, se quedó sólo unos instantes y volvió a salir. Se quedó sólo un minuto en «The Peacock», en la calle Sullivan. Incluso «The Gentlemen's Gathering», dos manzanas más al oeste, sólo mereció una breve visita. En la estrecha calle Pell, donde un cerdo muerto había atraído a una jauría de perros, el cochero detuvo sus caballos frente a una taberna destartalada bajo el letrero «Scuoiamuli». Mientras el caballero de negro entraba en la taberna, el cochero se bajó el sombrero y reflexionó sobre la conveniencia de regresar a los campos de patatas.

En el interior del «Scuoiamuli», un abigarrado grupo de borrachos, jugadores y alborotadores se ocupaba de sus propios asuntos a la pálida luz amarillenta de una lámpara. El humo flotaba en la habitación en densas capas; el caballero de negro arrugó su fina nariz ante el penetrante olor que mezclaba whisky barato, cigarros baratos y ropa empapada por la lluvia. Alguien se volvió hacia él, evaluándolo como una víctima lucrativa, pero los anchos hombros y la fuerza de la mirada del elegante hombre aconsejaban mirar a otra parte. La lluvia y la humedad habían embotado las intenciones criminales incluso del asesino más curtido.

El recién llegado se acercó a la barra, donde un hombre moreno con pantalones de piel de ante llenaba una jarra de cerveza de barril, y pronunció un nombre.

El camarero esbozó una sonrisa de satisfacción y se encogió de hombros. El hombre elegante deslizó una moneda de oro sobre la tosca barra de madera de pino y vio destellos de codicia en los ojos negros del tabernero. El tabernero alargó la mano para coger el dinero... y un bastón con una cabeza de león de plata como empuñadura lo estampó contra la madera. El caballero negro volvió a escudriñar el nombre, en voz baja y apagada.

«En la esquina». El camarero señaló con la cabeza a un cliente que estaba sentado solo, concentrado en garabatear algo a la luz de una lámpara humeante. «Usted no es policía, ¿verdad?».

«No.

«No quisiera meterle en problemas. Es el Shakespeare de América, ya sabe».

«No, no lo sé». Levantó su bastón; la mano del otro hombre cayó sobre la moneda como una araña.

El caballero de negro caminó enérgicamente hacia la figura aislada que escribía a la luz de la lámpara. Sobre una mesa de tablones arañados, frente al escritor, había un tintero, un montón de papel de escribir azul de mala calidad, una botella de jerez medio vacía y un vaso sucio. El suelo estaba cubierto de papeles arrugados y desechados. El escritor estaba pálido y delgado, con los ojos grises velados, garabateando en una hoja de papel con una pluma sostenida por una mano delgada y nerviosa. Dejó de escribir para apretarse el puño contra la frente y luego permaneció inmóvil un instante, como presa de un vacío mental. Arrugó el papel frunciendo el ceño y maldiciendo amargamente, y luego lo tiró al suelo, donde rebotó en la punta de la bota del caballero.

El escritor levantó la vista hacia el rostro del otro hombre, que parpadeó confundido, con el brillo del sudor de la fiebre que le corría por las mejillas y la frente.

«¿Señor Edgar Poe?», preguntó en voz baja el hombre de negro.

«Sí», respondió el escritor con voz entre enferma y jerezana. «¿Quién es usted?»

«Hace tiempo que deseaba conocerle... señor. ¿Puedo sentarme?»

Poe se encogió de hombros y señaló una silla. Tenía bolsas oscuras bajo los ojos, los labios grises y blandos, y el traje marrón barato que llevaba estaba manchado de barro y moho. Su camisa de lino blanco y su pañuelo negro raído estaban manchados de manchas de jerez; los puños raídos que salían de su abrigo parecían los de un pobre colegial. El escritor irradiaba un calor febril: le sacudió un repentino escalofrío, dejó la pluma y se llevó una mano temblorosa a la frente; sus ojos oscuros brillaban, y entre su fino bigote negro se veían unas gotitas que brillaban a la luz amarilla de la lámpara. Tosió fuerte y vigorosamente. «Disculpe», dijo. «No me encuentro bien».

El caballero colocó su bastón sobre la mesa, con cuidado de no tocar las hojas de papel y el tintero, y luego se sentó. Una corpulenta camarera se acercó inmediatamente para preguntarle qué quería tomar, pero el hombre la apartó con un firme gesto de la mano.

Durante generaciones, la Casa Usher ha prosperado y enriquecido mediante la creación y venta de armas de guerra mortíferas.

Pero una entidad maligna vivió y se desarrolló dentro de la casa, un legado remoto de depravación y sangre que ensucia los pasillos de la finca familiar...

Inspirado libremente en "La caída de la Casa Usher" de Edgar Allan Poe, McCammon se insinúa hábilmente en el trama original, planteando una duda: ¿y si la historia no hubiera terminado con la muerte de Roderick y Madeline, hace más de cien años? ¿Y si hubiera habido un hermano que continuara con el apellido y heredara su deplorable herencia manchada de sangre?

Set in present-day North Carolina, ‘The Usher Curse’ begins with the homecoming of Rix, a failed writer with a marriage that ended in tragedy. He is awaited by his father on his deathbed.

Rix is a convinced pacifist and has no intention of taking over the $10 billion business he is predestined for. But the House has chosen him: he will inherit the reins, not only to the opulent inheritance, which is said to be cursed, but also to the horrifying and terrible secrets that inhabit and rule the House of Usher. )

The thunder rang out like an iron bell over New York City, now the victim of a savage policy of urban sprawl. In the heavy air, lightning crackled and thundered to the ground, crashing into the Gothic steeple of James Renwick's new Grace Church on East Tenth Street and incinerating a half-blind draft horse plodding along the squatters' esplanade north of 14th Street. The animal's owner screamed in terror and tried to save himself by jumping from the overturning cart, plunging his load of potatoes into six inches of mud.

It was 22 March 1847 and the New York Tribune weatherman had predicted a night of ‘frightful thunderstorms, absolutely forbidding to both man and beast’. For once, his prediction had been right. Sparks exploded in the sky above Market Street, where the cast-iron chimney of a hardware store had been electrocuted by lightning. The slatted wood-clad building burned violently, while a crowd stared open-mouthed at the fire and smiled broadly at its glowing heat. Fire trucks with their hoses slowed as wooden wheels and horses' hooves became mired in the slush of the Bowery. Packs of dogs, rats and pigs fled through the alleys, where gangs like the Dover Boys, the Plug Uglies and the Moan Stickers stalked their victims along the cobblestones of the narrow streets. The cops cared more about their own skins than their duty, and so they remained safely tucked away under the gas lamps like so many statues...

New York was a young city, but already in the throes of decay. It offered a violent spectacle, full of dangers - the truncheons of thugs, for one thing - but also of opportunities, like a purse brimming with gold coins. Turmoil swept the streets from the docks to the theatres, from the dance halls to the brothels, from Murder Bend to City Hall with equal fairness, even if some avenues were impassable due to swamps of debris and rubbish.

The thunder rumbled again and the disturbed sky opened up in a torrent. It drenched damsels and maidens exiting the doors of the Delmonico3 restaurant, crashed against the tall windows above Colonnade Row and dripped black soot from the roofs of squatters' shacks. The rain put out fires, broke up brawls, encouraged indecent propositions or murderous assaults, and cleared the streets in a slow stream of filth that flowed towards the river. For that brief interval, at least, the human morass of the night was halted.

Two Barbary Saurian horses were dragging a black landau down Broadway Avenue, heading south towards the harbour, heads bowed in the downpour. The Irish coachman was huddled inside his soggy brown coat; he saw the water dripping from the brim of his lowered hat and cursed the decision he had made that afternoon to park near the De Geyser Hotel on Canal Street. Dejected, he thought that if he hadn't picked up that passenger, he'd be at home warming his feet in front of the fire with a nice glass of stout by his side. At least he had a golden eagle in his pocket... but what good would it do him if he died of pneumonia? He brandished his whip, striking a feeble blow at the flank of one of the horses, though he knew they would go no faster, but damn it, he thought. Damn it, he thought, what was this passenger after?

The gentleman had boarded in front of De Peyser, placed a golden eagle in the coachman's hand, and told him to drive as quickly as possible to the Tribune office. Having ordered him to stay and wait for him, the coachman had let the horses rest until the man in black reappeared a quarter of an hour later and assigned him a new destination. It was a long ride through the countryside, to a place on the outskirts of Fordham, in the shadow of the Long Island hills, as the purple-tinged storm clouds began to thicken and thunder rumbled in the distance. Arriving at a small, shabby-looking cottage, a plump, middle-aged woman with grey hair and startled eyes had greeted the gentleman - very reluctantly, as far as the coachman had seen. After another half hour in which a downpour of freezing rain had left the coachman in danger of having to resort to warm balm and scrubbing with wintergreen oil, the black-clad passenger had reappeared with a new set of instructions: get back to New York as soon as possible, so as to get through a lot of cheap taverns in the lower part of the city. The Triangle to the south! And at night! thought the coachman grimly. The gentleman had in mind a cheap tart, or a brush with death.

As they proceeded south through lawless streets, the coachman was relieved to see that the pouring rain kept most of the criminals at home. Praise the saints, he thought... and at that moment two ragged young men came running out of an alley towards the carriage. The coachman saw with horror that one of them was carrying a brick in his hand, probably with the intention of breaking the spokes of a wheel - the best way to hit him and rob both him and the passenger. He swung his whip wildly, shouting, ‘Forward! Forward!’ and the cavalcade of horses, sensing the impending danger, galloped over the slippery stones. The brick flew off, but ended up against the side of the carriage, splintering its wood with a dry clatter. ‘Forward!’ the coachman shouted again, keeping the horses at a brisk pace until the hooligans were left behind.

The sliding partition behind the coachman's box opened, ‘Coachman,’ the passenger asked, ‘what was that? His voice was calm and firm: he is used to giving orders, the man thought.

‘Excuse me, sir, but...’. He glanced over his shoulder through the partition and saw in the pale light of the interior lamp the pale, haggard face of the customer, characterised by a silvery, well-groomed beard and moustache. The gentleman's eyes were sunken and shone the colour of burnished pewter, fixed on the coachman with that typical aristocratic look. The gentleman looked strangely aged, his face free of telltale wrinkles, his flesh white as marble. He wore a black suit and a shining top hat; his sharp-fingered hands, wrapped in black leather gloves, fiddled with an ivory cane whose hilt was formed by a magnificent silver feline head - a lion, the coachman had recognised - with gleaming emerald eyes.

‘But what?’ the man asked. The coachman could not recognise the accent.

Sir... it's not very safe to drive here. You look like a refined and respectable gentleman, and there aren't many of those to be found in this part of the...’

‘Just worry about driving,’ the man warned him. ‘You're wasting your time.’ He closed the sliding partition.

The coachman grumbled, his beard soaked with rain, and urged the horses on. A golden eagle can't induce a man to do anything, he thought. But at least it would give him a good time at the bar.

‘Sandy the Welshman's Cellar, a bar on Ann Street, was the first stop. The gentleman went in, stayed only a few moments and came out again. He stayed only a minute at ‘The Peacock’ on Sullivan Street. Even The Gentlemen's Gathering, two blocks further west, was worth only a brief visit. On narrow Pell Street, where a dead pig had attracted a pack of dogs, the coachman stopped his horses in front of a ramshackle tavern under the sign ‘Scuoiamuli’. As the gentleman in black entered the tavern, the coachman lowered his hat and pondered whether to return to the potato fields.

Inside the ‘Scuoiamuli’, a motley group of drunks, gamblers and rowdies were minding their own business in the pale yellowish light of a lamp. Smoke hung in the room in thick layers; the gentleman in black wrinkled his fine nose at the pungent smell that mixed cheap whisky, cheap cigars and rain-soaked clothes. Someone turned to him, assessing him as a lucrative victim, but the broad shoulders and the strength of the elegant man's gaze made it advisable to look away. The rain and humidity had dulled the criminal intentions of even the most hardened assassin.

The newcomer approached the bar, where a dark-haired man in buckskin trousers was filling a tankard of draught beer, and called out a name.

The bartender smirked and shrugged. The elegant man slid a gold coin over the rough pinewood bar and saw glints of greed in the barkeep's black eyes. The tavern keeper reached out to take the money... and a cane with a silver lion's head for a hilt slammed it against the wood. The black knight scanned the name again, in a low, muffled voice.

‘In the corner.’ The waiter nodded to a customer sitting alone, intent on scribbling something by the light of a smoking lamp. ‘You're not a policeman, are you?

‘No.’ ’I wouldn't want to get you in trouble.

‘I wouldn't want to get you in trouble. You're America's Shakespeare, you know.’

‘No, I don't.’ He raised his baton; the other man's hand fell on the coin like a spider.

The gentleman in black walked briskly toward the isolated figure writing by lamplight. On a scratched plank table in front of the writer was an inkwell, a pile of shoddy blue writing paper, a half-empty bottle of sherry and a dirty glass. The floor was littered with crumpled and discarded papers. The writer was pale and thin, his grey eyes veiled, scribbling on a sheet of paper with a pen held in a thin, nervous hand. He stopped writing to press his fist to his forehead and then stood still for a moment, as if in a mental vacuum. He crumpled the paper in a frown and cursed bitterly, then threw it to the ground, where it bounced off the toe of the gentleman's boot.

The writer looked up into the face of the other man, who blinked in confusion, the sheen of fever sweat running down his cheeks and forehead.

‘Mr. Edgar Poe?’ the man in black asked quietly.

‘Yes,’ replied the writer in a voice somewhere between sick and sherry. ‘Who are you?’

‘I have long wished to meet you... sir. May I sit down?’

Poe shrugged and pointed to a chair. He had dark bags under his eyes, his lips grey and soft, and the cheap brown suit he wore was stained with mud and mildew. His white linen shirt and threadbare black handkerchief were stained with sherry stains; the ragged cuffs that came out of his coat looked like those of a poor schoolboy. The writer radiated a feverish heat: he was shaken by a sudden chill, put down his pen, and raised a trembling hand to his forehead; his dark eyes glittered, and between his thin black moustache a few droplets glistened in the yellow light of the lamp. He coughed loudly and vigorously. ‘Excuse me,’ he said. ‘I don't feel well.’

The gentleman placed his cane on the table, careful not to touch the sheets of paper and the inkwell, and then sat down. A portly waitress immediately approached him to ask what he wanted to drink, but he pushed her away with a firm hand gesture.

For generations, House Usher has prospered and grown rich through the creation and sale of deadly weapons of war.

But an evil entity lived and thrived within the house, a distant legacy of depravity and blood that litters the halls of the family estate...

Loosely inspired by Edgar Allan Poe's ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, McCammon deftly hints at the original plot, raising a question: what if the story hadn't ended with the death of Roderick and Madeline, over a hundred years ago? What if there had been a brother to carry on the family name and inherit its deplorable, blood-stained legacy?

Source images / Fuente imágenes: Robert McCammon.

Fuente de la imagen banner final post / Image source banner final post.