To talk about this novel, let us start from the beginning, and the beginning is an Italian title that in my mind mimics King's Sometimes They Come Back and shifts the focus from the where - the city, the true focus of this McCammon novel - to the who.

The where in which much of the story told in Them Bethany's Sin takes place is a clean and neat, if a little too quiet, urban suburb. And if it is true that nomen omen, about a town that carries the word sin in its name, I would ask myself a few questions before going to live there with the whole family.

Because, although Bethany's sin seems like the ideal place to raise your children, it must also be said that behind so many friendly smiles hides the grin of people who dream of hanging a man's severed head on their mantelpiece.

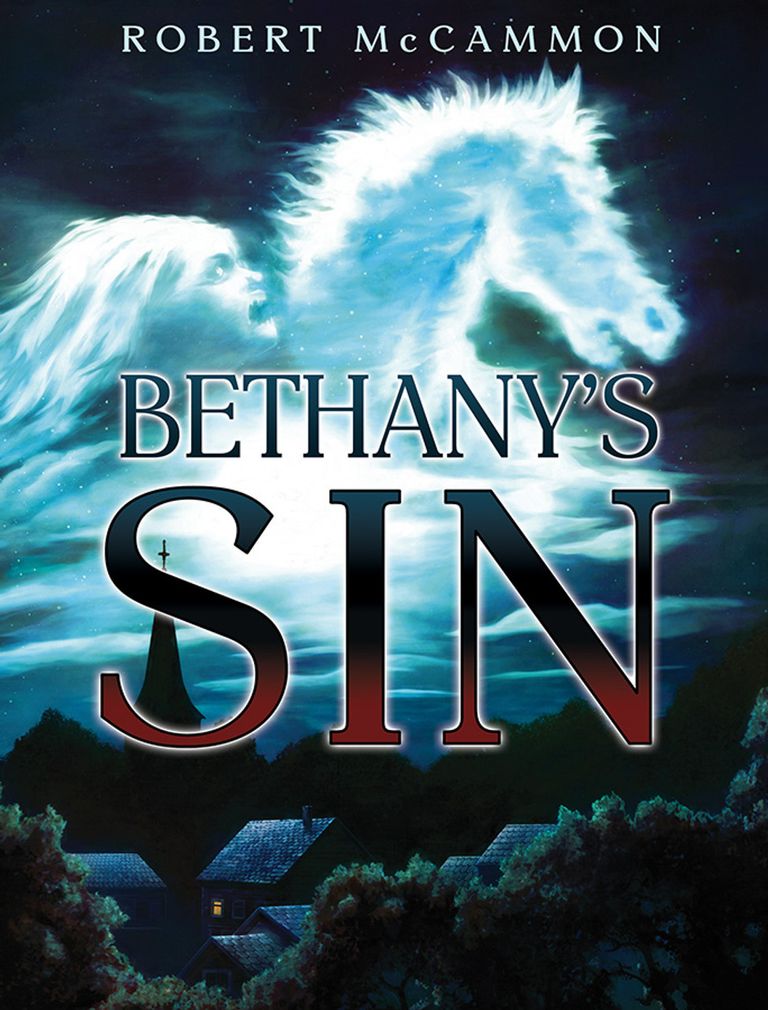

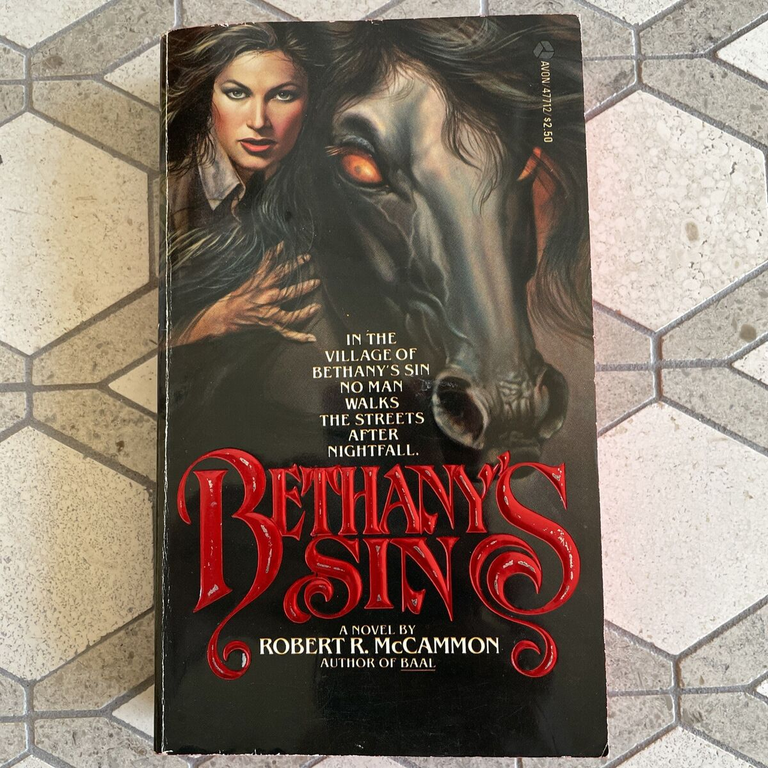

Bethany's Sin in the original] is Robert McCammon's third effort as an author after Baal, a dazzling debut by a boy who had just turned twenty-six at the time.

When he wrote Bethany's Sin McCammon was twenty-eight years old. Not much time has passed since his first novel, but already the pressure must be mounting. After all, if you have to measure yourself against King on a daily basis - a gigantic touchstone for anyone who has any success in the field of genre fiction - you end up having to churn out novels in order to periodically feed a machine, the publishing machine, that chews you up until it has succeeded in consuming you completely.

To McCammon this happens some fifteen years after his debut. It is 1992, by then he has thirteen novels and collections under his belt (an average of one book a year), and probably exhausted, he decides to take a long break from the typewriter.

Either that or throw himself into alcohol, King would say.

But barely two years after Baal McCammon is still a young man of great promise. So, in 1980 he signed the contract for this novel about a Vietnam veteran who finds himself confronted by a handful of revived Amazons.

Para hablar de esta novela, empecemos por el principio, y el principio es un título que en mi mente imita a A veces vuelven de King y desplaza el foco del dónde -la ciudad, el verdadero foco de esta novela de McCammon- al quién.

El dónde en el que transcurre gran parte de la historia que se cuenta en Bethany's Sin es un suburbio urbano limpio y ordenado, aunque un poco demasiado tranquilo. Y si es cierto ese nomen omen, sobre una ciudad que lleva la palabra pecado en su nombre, yo me haría unas cuantas preguntas antes de irme a vivir allí con toda la familia.

Porque, aunque Bethany's sin parezca el lugar ideal para criar a tus hijos, también hay que decir que detrás de tantas sonrisas amables se esconde la mueca de gente que sueña con colgar la cabeza cortada de un hombre en su repisa de la chimenea.

Bethany's Sin en el original] es el tercer esfuerzo de Robert McCammon como autor después de Baal, un deslumbrante debut de un chico que acababa de cumplir veintiséis años en aquel momento.

Cuando escribió Bethany's Sin, McCammon tenía veintiocho años. No ha pasado mucho tiempo desde su primera novela, pero la presión ya debe de estar aumentando. Al fin y al cabo, si tienes que medirte a diario con King -una gigantesca piedra de toque para cualquiera que tenga algún éxito en el campo de la ficción de género-, acabas teniendo que producir novelas para alimentar periódicamente una máquina, la máquina editorial, que te mastica hasta que consigue consumirte por completo.

A McCammon esto le ocurre unos quince años después de su debut. Estamos en 1992, para entonces ya tiene trece novelas y colecciones en su haber (una media de un libro al año) y, probablemente agotado, decide tomarse un largo descanso de la máquina de escribir.

O eso o tirarse al alcohol, diría King.

Pero apenas dos años después de Baal, McCammon sigue siendo un joven prometedor. Así que en 1980 firma el contrato para esta novela sobre un veterano de Vietnam que se ve enfrentado a un puñado de amazonas resucitadas.

If we wanted to read the novel using solely the lens of metaphor, we could say that Bethany's Sin is the story of a man against war.

On the one hand, we have Evan Reid, the protagonist, who has lived in hell, suffered imprisonment and torture and managed, laboriously, to escape from it. On the other are women who make battle and carnage their only reason for living.

In fact, however, there is more.

These are difficult years for the USA. It is a dark and disastrous period politically and socially: skyrocketing unemployment and marginalisation of the poorer classes on the one hand, progressive conservatism of the upper class on the other.

It is the season of Reagan and of a society that would happily lock up the poor in a ghetto, never to be thought of again.

So those who could leave the cities to take refuge in those beautiful urban suburbs that knew, in this period, the height of their development.

The 1980s were also the years of Dawn of the Living Dead, Society and They Live, just to mention films that exploited horror and the grotesque to tell the story of a very specific historical period.

In this climate of uncertainty and mistrust, where nothing is needed to find yourself in the middle of the road and where every opportunity that comes your way must be grabbed without thinking too much about it, the Reids' story is set.

He, Evan, a veteran who has prophetic dreams and ambitions as a writer, she, Kay, who endures her husband's visions with difficulty and drags everyone to Bethany's Sin because she is providentially offered a job on the city campus. Just when they are in the most trouble, after Evan loses his job for almost trying to kill his boss.

You see the coincidences.

Life in Bethany's Sin is great, if it weren't for the fact that the neighbours are so perfect they seem fake. The streets with little traffic, community life stripped down to the bone.

Quiet place. Yeah. A place far too quiet.

Let's go back a decade or so for a moment. It is 1972 and Ira Levin gives us the fine novel that is Stepford Wives. There, too, an urban suburb that would make more than one real estate agent's mouth water hides, under the veneer of a place of luxury destined for the middle class, a small amusement park of horrors.

If I have chosen to bring up Levin, it is not to show that I can construct a conceptual map, but because the stories seem like mirror versions of each other.

In Stepford we were inside a community dominated by the Men's Club, whose ultimate aim was to turn their female companions into sexually fulfilling robots. In Bethany's Sin, on the other hand, it is the women who co-opt themselves into turning their husbands into sex slaves, crippling them like any Annie Wilkes so they won't run away, and using them to beget sons. Or rather, daughters, because the boys are mostly offered to Mother Nature and thrown away as useless scraps (and if this seems excessive, remember that we live in an era where female infanticide is still a widespread scourge).

In short, in Bethany's sin we find ourselves in a community where the relationship between the sexes has been turned upside down, with men reduced to a necessary evil when useful for reproduction or, at worst, turned into amusing prey to be hunted on moonlit nights.

The idea is interesting. The development a little less so.

Certainly, credit must be given to McCammon for having attempted to renew the topos of the haunted city by using an ancient and legendary lineage of warriors as a corrupting agent. The reference to mythology - albeit a repurposed mythology - is continuous. Evan pits himself against the Queen-Mayor of the Amazons as in a modern re-edition of the myth of Achilles and Penthesilea, contributing to the epic nature of the final clash. Just as curious is the interpretation given of the splendid Artemis Ephesia.

Yet the women of Bethany's sin lack one important thing: will. Those who act against Evan and the other men are not the women who set foot in Bethany's sin in the wake of a moving lorry but their wrappings, in which the spectres of the last Amazons have lurked.

Mind you. I realise that it was probably not McCammon's intention to start a debate on gender relations with a horror novel but, from my point of view, that of the struggle between genders has become a macro-theme that has taken over the story. And, inevitably, over the review.

The problem is that throughout the novel there is not a single female figure worth mentioning. They are all either incapable of defending themselves against the influence of the queen-mayor (this is the case with Evan's wife Kay) or fatuous one-liners.

And this is the thing that, while reading, stood out in front of me like the head of a two-metre tall man sitting in front of you at the cinema, disturbing you while watching the film.

To put it succinctly: in Them Waiting there is not a single female character who has any depth in profile. Yet it is a novel where women play a central role. The only one who deviates from this flatness is the mayor of Bethany's sin, but even in her the will is now subservient to the power of the Amazons.

The women of Bethany's sin are weak, suggestible creatures. They acquire strength and power only when the Amazons possess them, ceasing to exist.

The example is set by Kay, Evan's wife. If McCammon had chosen her in the role of the hero, I am convinced that the whole novel would have gained not only in originality but in the strengthening of the central theme, which is about facing one's fears and weaknesses at the cost of one's life.

So instead we have the character of an obtuse, somewhat hysterical woman who denies the evidence to the point of almost dying and who is saved only because her husband comes to her rescue, sacrificing himself for her.

To this which, for me, is the biggest flaw in the narrative structure is added a less than optimal handling of suspense.

And here, again, I am forced to draw comparisons with Levin.

If in Stepford Wives we do not realise, until the very last chapter, that Joanna's pathurnias are not really pathurnias at all, that there really is something wrong with her neighbours, here McCammon's attempt to play up the element of surprise fails without appeal.

The impression one gets while reading is that the author was uncertain until the very end whether to reveal the nature of the cheerful community of Bethany's Sin right away, or keep everything hidden for the grand finale.

It doesn't work. It doesn't work because that in Bethany's Sin the women are not what they seem we understand practically from the first meeting with the neighbours.

We understand it but not the protagonist who, despite premonitory dreams takes half the novel to realise that he should pack up and leave immediately.

And yes, the solution is practically shouted into his ear by their neighbour's mutilated husband.

But there's more.

The moment comes when Evan becomes convinced that all the women around him are crazy murderers. Yet, despite the elephant dancing in his bedroom, he doesn't blink an eye when the doctor at the community's only medical centre tells him that he has to take in his wife, who by then has already proved that she is no longer herself, so that she can be tested.

The funniest thing about that scene? The fact that Evan is not forced to hand over his wife the very night the doctor barges in on him. No. He quietly has her admitted the next morning. When most of you would have already boarded the first one-way flight to Alaska.

This is the moment when the whole mechanism of the novel is revealed, a mechanism that should have remained shielded from the reader's eyes. McCammon needs Kay to go to the hospital. He needs Evan to be alone. He needs him for the novel's closure. And he does this by sending logic out to pick daisies.

Si quisiéramos leer la novela utilizando únicamente la lente de la metáfora, podríamos decir que El pecado de Bethany es la historia de un hombre contra la guerra.

Por un lado, tenemos a Evan Reid, el protagonista, que ha vivido en el infierno, ha sufrido el encarcelamiento y la tortura y ha conseguido, trabajosamente, escapar de él. Por otro, están las mujeres que hacen de la batalla y la carnicería su única razón de vivir.

En realidad, sin embargo, hay más.

Son años difíciles para Estados Unidos. Es un periodo oscuro y desastroso política y socialmente: desempleo desorbitado y marginación de las clases más pobres por un lado, conservadurismo progresista de la clase alta por otro.

Es la época de Reagan y de una sociedad que encerraría alegremente a los pobres en un gueto, para no volver a pensar en ellos.

Así que los que pudieron abandonaron las ciudades para refugiarse en esos hermosos suburbios urbanos que conocieron, en esta época, el apogeo de su desarrollo.

Los años 80 fueron también los del Amanecer de los muertos vivientes, La sociedad y Ellos viven, por citar sólo algunas películas que explotaban el terror y lo grotesco para narrar un periodo histórico muy concreto.

En este clima de incertidumbre y desconfianza, en el que no hace falta nada para encontrarse en medio de la carretera y en el que cada oportunidad que se presenta hay que aprovecharla sin pensárselo demasiado, se desarrolla la historia de los Reid.

Él, Evan, un veterano que tiene sueños proféticos y ambiciones como escritor; ella, Kay, que soporta a duras penas las visiones de su marido y arrastra a todo el mundo a Bethany's Sin porque le ofrecen providencialmente un trabajo en el campus de la ciudad. Justo cuando más problemas tienen, después de que Evan pierda su trabajo por casi intentar matar a su jefe.

Ya ves las coincidencias.

La vida en Bethany's Sin es estupenda, si no fuera porque los vecinos son tan perfectos que parecen falsos. Las calles con poco tráfico, la vida de la comunidad despojada hasta los huesos.

Un lugar tranquilo. Sí. Un lugar demasiado tranquilo.

Retrocedamos una década más o menos por un momento. Es 1972 e Ira Levin nos da la buena novela que es Stepford Wives. También allí, un suburbio urbano que haría la boca agua a más de un agente inmobiliario esconde, bajo el barniz de un lugar de lujo destinado a la clase media, un pequeño parque de atracciones de los horrores.

Si he optado por traer a colación a Levin, no es para demostrar que puedo construir un mapa conceptual, sino porque las historias parecen versiones especulares la una de la otra.

En Stepford estábamos dentro de una comunidad dominada por el Club de Hombres, cuyo fin último era convertir a sus compañeras en robots sexualmente satisfactorios. En El pecado de Bethany, en cambio, son las mujeres las que se cooptan para convertir a sus maridos en esclavos sexuales, lisiándolos como a cualquier Annie Wilkes para que no huyan, y utilizándolos para engendrar hijos. O mejor dicho, hijas, porque los varones son en su mayoría ofrecidos a la Madre Naturaleza y desechados como chatarra inútil (y si esto les parece excesivo, recuerden que vivimos en una época en la que el infanticidio femenino sigue siendo una lacra generalizada).

En definitiva, en el pecado de Betania nos encontramos con una comunidad en la que la relación entre los sexos se ha puesto patas arriba, con los hombres reducidos a un mal necesario cuando son útiles para la reproducción o, en el peor de los casos, convertidos en divertidas presas a las que dar caza en las noches de luna.

La idea es interesante. El desarrollo, un poco menos.

Ciertamente, hay que reconocerle a McCammon el mérito de haber intentado renovar el topos de la ciudad encantada utilizando un antiguo y legendario linaje de guerreros como agente corruptor. La referencia a la mitología -aunque sea una mitología reutilizada- es continua. Evan se enfrenta a la Reina-Alcaldesa de las Amazonas como en una reedición moderna del mito de Aquiles y Pentesilea, lo que contribuye al carácter épico del enfrentamiento final. Igual de curiosa es la interpretación que se hace de la espléndida Artemisa Efesia.

Sin embargo, a las mujeres del pecado de Betania les falta algo importante: voluntad. Quienes actúan contra Evan y los demás hombres no son las mujeres que pisan el pecado de Betania tras la estela de un camión en marcha, sino sus envoltorios, en los que han acechado los espectros de las últimas Amazonas.

Eso sí. Soy consciente de que probablemente no era la intención de McCammon iniciar un debate sobre las relaciones de género con una novela de terror pero, desde mi punto de vista, el de la lucha entre géneros se ha convertido en un macrotema que se ha adueñado de la historia. E, inevitablemente, de la crítica.

El problema es que a lo largo de la novela no hay ni una sola figura femenina digna de mención. Todas son o bien incapaces de defenderse de la influencia de la reina-alcaldesa (es el caso de Kay, la mujer de Evan) o bien fatuas de una sola línea.

Y esto es lo que, mientras leía, me llamó la atención como la cabeza de un hombre de dos metros de altura sentado frente a ti en el cine, molestándote mientras ves la película.

Para decirlo sucintamente: en Ellos esperan no hay ni un solo personaje femenino que tenga profundidad de perfil. Sin embargo, es una novela en la que las mujeres desempeñan un papel central. La única que se desvía de esta planitud es la alcaldesa del pecado de Betania, pero incluso en ella la voluntad queda supeditada al poder de las amazonas.

Las mujeres del pecado de Betania son criaturas débiles y sugestionables. Sólo adquieren fuerza y poder cuando las Amazonas las poseen, dejando de existir.

El ejemplo lo da Kay, la esposa de Evan. Si McCammon la hubiera elegido en el papel del héroe, estoy convencido de que toda la novela habría ganado no sólo en originalidad, sino en el fortalecimiento del tema central, que trata de enfrentarse a los propios miedos y debilidades a costa de la propia vida.

Así que en lugar de eso tenemos el personaje de una mujer obtusa y algo histérica que niega la evidencia hasta el punto de casi morir y que se salva sólo porque su marido acude en su rescate, sacrificándose por ella.

A esto que, para mí, es el mayor defecto de la estructura narrativa se añade un manejo poco óptimo del suspense.

Y aquí, de nuevo, me veo obligado a establecer comparaciones con Levin.

Si en Stepford Wives no nos damos cuenta, hasta el último capítulo, de que las paturnias de Joanna no son realmente paturnias, de que a sus vecinos les pasa realmente algo, aquí el intento de McCammon de jugar con el elemento sorpresa fracasa sin remedio.

La impresión que uno tiene mientras lee es que el autor estuvo dudando hasta el final si revelar la naturaleza de la alegre comunidad de Bethany's Sin de inmediato, o mantenerlo todo oculto para el gran final.

No funciona. No funciona porque que en Bethany's Sin las mujeres no son lo que parecen lo entendemos prácticamente desde el primer encuentro con las vecinas.

Lo entendemos pero no el protagonista que, a pesar de los sueños premonitorios tarda media novela en darse cuenta de que debe hacer las maletas y marcharse inmediatamente.

Y sí, la solución se la grita prácticamente al oído el marido mutilado de su vecina.

Pero aún hay más.

Llega el momento en que Evan se convence de que todas las mujeres que le rodean son unas locas asesinas. Sin embargo, a pesar del elefante que baila en su habitación, no pestañea cuando el médico del único centro médico de la comunidad le dice que tiene que llevar a su mujer, que para entonces ya ha demostrado que ya no es ella misma, para que le hagan pruebas.

¿Lo más gracioso de esa escena? El hecho de que Evan no se vea obligado a entregar a su mujer la misma noche en que el médico irrumpe en su casa. No. La ingresa tranquilamente a la mañana siguiente. Cuando la mayoría ya habría embarcado en el primer vuelo de ida a Alaska.

Este es el momento en que se revela todo el mecanismo de la novela, un mecanismo que debería haber permanecido oculto a los ojos del lector. McCammon necesita que Kay vaya al hospital. Necesita que Evan esté solo. Lo necesita para cerrar la novela. Y lo hace enviando a la lógica a recoger margaritas.

Unfortunately, a style that is rich in images and strongly evocative - a style of writing capable of making the page transparent by allowing the reader to see the scene described - is not enough to lift the judgement on a novel in which the central theme is developed out of inertia and in which the protagonist has an arc of transformation that seems forced compared to the development of the plot.

In conclusion, They Wait is a novel that I would potentially recommend to those nostalgic for a certain way of doing horror, a brother of the 1980s. But, then again, I wouldn't bother looking for it.

Por desgracia, un estilo rico en imágenes y fuertemente evocador -una escritura capaz de transparentar la página permitiendo al lector ver la escena descrita- no es suficiente para levantar el juicio sobre una novela en la que el tema central se desarrolla por inercia y en la que el protagonista tiene un arco de transformación que parece forzado en comparación con el desarrollo de la trama.

En conclusión, Ellos esperan es una novela que potencialmente recomendaría a los nostálgicos de cierta forma de hacer terror, hermano de los años ochenta. Pero, por otra parte, yo no me molestaría en buscarla.

Source images / Fuente imágenes: Robert McCammon.

Fuente de la imagen banner final post / Image source banner final post.

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks to the team of curators at @ctime for promoting the dissemination of content on #BLURT