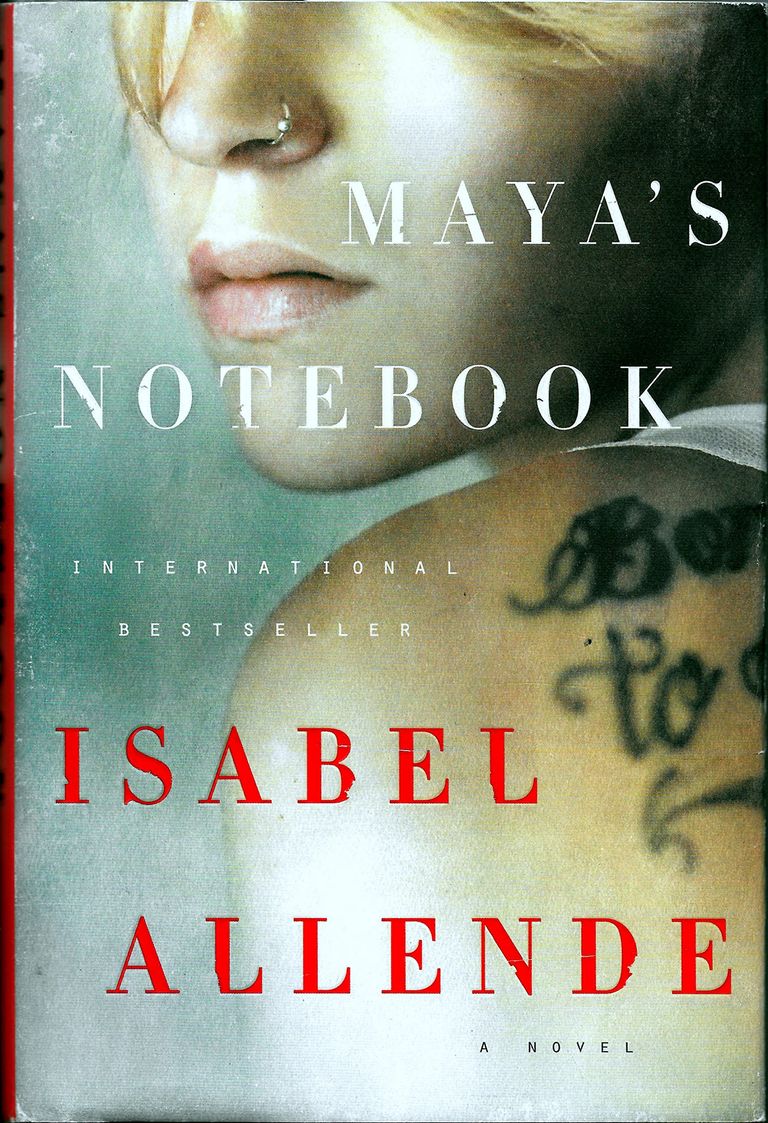

Maya Vidal, the teenage protagonist of Isabel Allende's new novel, who has fallen into the circuit of alcohol and drugs, manages to re-emerge from the slums of Las Vegas and, on the run from drug dealers and FBI agents, lands in the pristine Chiloé archipelago.

On these remote islands in southern Chile, in the atmosphere of a simple life of magnificent sunsets, solid values and mutual respect, Maya learns about herself and her homeland, discovers hidden truths and, finally, love. These pages are interspersed with the raw account of her difficult previous history, a life of marginality and degradation, loneliness and bad company, into which she plunges after the death of her beloved grandfather. Isabel Allende returns to chronicle the life of a courageous woman in a novel that delicately deals with human relationships: unconditional friendships, love affairs as palpable as the most invisible ones, teenage and lifelong loves.

A brisk pace, disenchanted prose for this new narrative proof tinged with noir and yet another gallery of strong-willed women and men capable of love.

Most of the women who have sprung from the pen of the Chilean writer are indomitable beings who do not ask anyone's permission to live, love and make mistakes, and it is precisely on this union of character and fallibility that they build the premises for the visceral love that readers inevitably feel for them.

From the many protagonists of The House of the Spirits to Eva Luna, from the Inès of the eponymous novel to the Aurora of Portrait in Sepia, and on to the author herself and her daughter Paula, at the center of some of the most intense pages in Allende's very rich production, it is women who take center stage in the novels read and loved around the world for the past thirty years.

Take for example Maya, the protagonist of the latest The Notebook of Maya. Here it tells of the vicissitudes of Maya Vidal, a 19-year-old girl with a past more dense with events and drama than a Latin American soap. Raised by her grandparents, the beloved Popo, and his wife Nini, Maya spends in her late teens a long period in Las Vegas that to call turbulent would be an understatement.

In fact, following the death of the man she will continue to call "My Popo," she finds herself in a dramatic existential whirlwind that throws all her coordinates out of whack and gets her into big trouble.

Big enough to the point that Nini-the grandmother-will find no other way out than to send Maya to an archipelago in Chile's far south, Chiloé, where the girl can find protection and hospitality while waiting for better times.

Protection is provided by the isolation that Chiloé offers each of its inhabitants, being a land cut off from any tourist route or economic interest. As for hospitality, Manuel, an anthropologist friend of Grandma Nini's, will provide it; he can understand Maya's many qualities and offer her a job. The contrast between the slum Las Vegas that Maya has been hanging out in during her troubled adolescence and the primordial, wild and unspoiled nature of Chiloé is effectively rendered by the writing, and the suggestion is further amplified by the discovery of a family secret kept in the at once Edenic and threatening environment of Chiloé.

The story of "Maya" is Allende's answer to the prayers of her grandchildren, who had long asked her for a book with characters they could identify with, a story that would present reasons for fascination even for today's children.

But it has to be said that the result is certainly not ascribable to the strand of children's literature, because many of the situations experienced or evoked by Maya in the course of the story are charged with a brutality decidedly unsuitable for an audience of very young readers.

It is, in short, what we have in our hands, a classic "à la Allende," with all the themes dear to the writer: exile and return, will and character as viatical to one's happiness, and - over all - the ability to fulfill oneself and grow in confrontation with others.

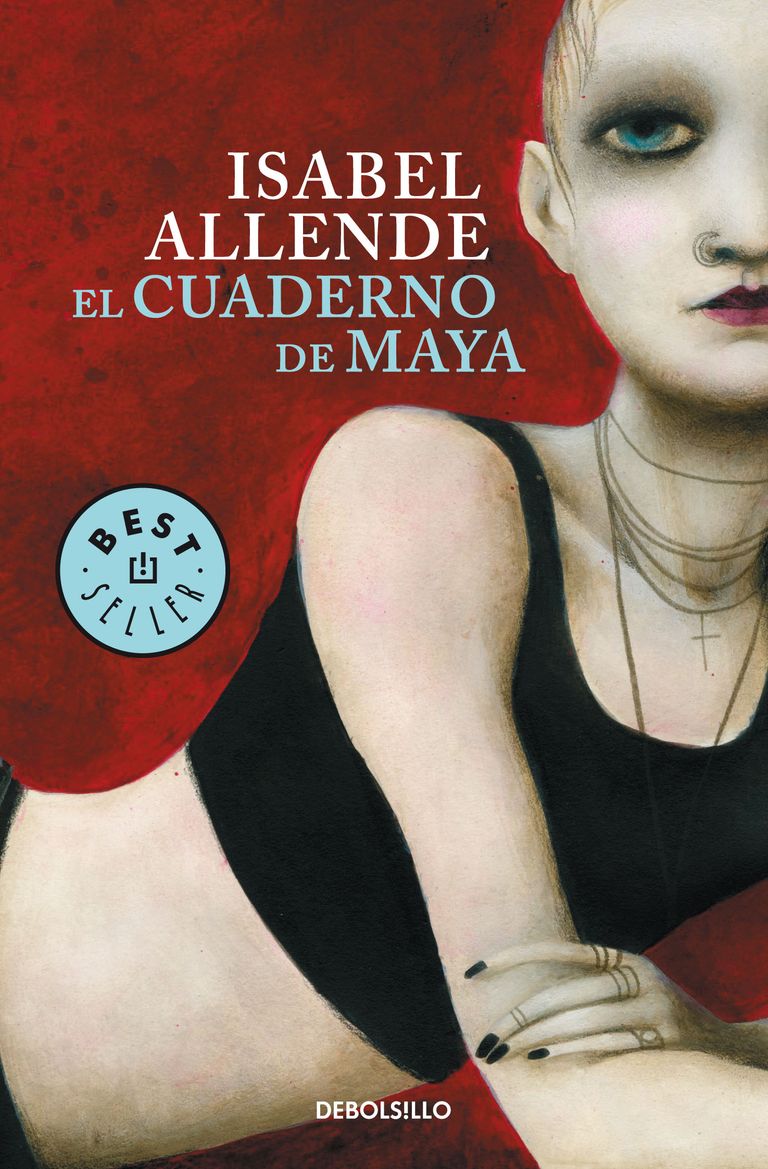

Maya Vidal, la adolescente protagonista de la nueva novela de Isabel Allende, que ha caído en el circuito del alcohol y las drogas, consigue resurgir de los tugurios de Las Vegas y, huyendo de narcotraficantes y agentes del FBI, desembarca en el prístino archipiélago de Chiloé.

En estas remotas islas del sur de Chile, en el ambiente de una vida sencilla de magníficos atardeceres, sólidos valores y respeto mutuo, Maya aprende sobre sí misma y su tierra natal, descubre verdades ocultas y, finalmente, el amor. Estas páginas se intercalan con el crudo relato de su difícil historia anterior, una vida de marginalidad y degradación, soledad y malas compañías, en la que se sumerge tras la muerte de su querido abuelo. Isabel Allende vuelve a narrar la vida de una mujer valiente en una novela que trata con delicadeza las relaciones humanas: amistades incondicionales, amores tan palpables como los más invisibles, amores adolescentes y para toda la vida.

de carácter fuerte capaces de amar.

La mayoría de las mujeres que han brotado de la pluma de la escritora chilena son seres indomables que no piden permiso a nadie para vivir, amar y equivocarse, y es precisamente sobre esa unión de carácter y falibilidad sobre la que construyen las premisas para el amor visceral que inevitablemente sienten los lectores por ellas.

Desde las numerosas protagonistas de La casa de los espíritus hasta Eva Luna, desde la Inés de la novela homónima hasta la Aurora de Retrato en sepia, pasando por la propia autora y su hija Paula, en el centro de algunas de las páginas más intensas de la riquísima producción de Allende, son las mujeres las que ocupan un lugar central en las novelas leídas y amadas en todo el mundo desde hace treinta años.

Tomemos por ejemplo a Maya, la protagonista del último El cuaderno de Maya. En ella se narran las vicisitudes de Maya Vidal, una joven de 19 años con un pasado más denso en acontecimientos y dramas que un culebrón latinoamericano. Criada por sus abuelos, el entrañable Popo, y la esposa de éste, Nini, Maya pasa al final de su adolescencia una larga temporada en Las Vegas que calificar de turbulenta sería quedarse corto.

De hecho, tras la muerte del hombre al que seguirá llamando "Mi Popo", se ve inmersa en un dramático torbellino existencial que desbarata todas sus coordenadas y la mete en un buen lío.

Tanto, que Nini -la abuela- no encuentra otra salida que enviar a Maya a un archipiélago del extremo sur de Chile, Chiloé, donde la niña puede encontrar protección y hospitalidad a la espera de tiempos mejores.

La protección viene dada por el aislamiento que Chiloé ofrece a cada uno de sus habitantes, al ser una tierra aislada de cualquier ruta turística o interés económico. En cuanto a la hospitalidad, se la proporcionará Manuel, un antropólogo amigo de la abuela Nini, capaz de comprender las muchas cualidades de Maya y ofrecerle un trabajo. El contraste entre el tugurio de Las Vegas por el que Maya ha estado pasando el tiempo durante su problemática adolescencia y la naturaleza primigenia, salvaje y virgen de Chiloé queda eficazmente plasmado en la escritura, y la sugerencia se amplifica aún más con el descubrimiento de un secreto familiar guardado en el entorno a la vez edénico y amenazador de Chiloé.

La historia de "Maya" es la respuesta de Allende a las plegarias de sus nietos, que desde hace tiempo le pedían un libro con personajes con los que pudieran identificarse, una historia que presentara motivos de fascinación incluso para los niños de hoy.

Pero hay que decir que el resultado no es ciertamente adscribible a la vertiente de la literatura infantil, porque muchas de las situaciones vividas o evocadas por Maya en el curso de la historia están cargadas de una brutalidad decididamente inadecuada para un público de lectores muy jóvenes.

Es, en definitiva, lo que tenemos entre manos, un clásico "a la Allende", con todos los temas queridos por la escritora: el exilio y el regreso, la voluntad y el carácter como vías para la propia felicidad y -sobre todo- la capacidad de realizarse y crecer en la confrontación con los demás.

A week ago, at the airport in San Francisco, my grandmother hugged me without crying and repeated that if I cared about my existence, I should not get in touch with anyone until we were sure that my enemies were no longer looking for me. My Nini is paranoid, like all the people of the Independent People's Republic of Berkeley, persecuted by the government and extra-ri, but in my case she was not exaggerating: any prevention would not be too much. He handed me a notebook with a hundred pages for me to keep a diary of my life as I had done from age eight to fifteen, when fate had not yet turned its back on me. "You will have time for yourself, Maya. Take the opportunity to write about the enormous nonsense you have committed, maybe that way you will realize the extent of it," she told me.

So as not to offend her, I put the notebook in my backpack, but I had no intention of using it, although here, indeed, time is diluted and writing is a way to occupy it. This first week of exile has been a long one for me. I find myself on a small island almost invisible on the map, dropped into the middle of the Middle Ages. I find it complicated to write about my life, because I do not distinguish between memories and what is a figment of my imagination; the pure truth can be tedious, and for this reason, without realizing it, I edit or emphasize it, although I have resolved to correct this defect and lie as little as possible in the future. And so it is that now, when even the Amazon yanomamis use computers, I find myself writing by hand. I proceed slowly and my handwriting looks Cyrillic, since even I cannot decipher it, but I imagine that page after page will begin to improve. Writing is like riding a bicycle: you don't forget it, no matter how many years go by without practicing. I try to proceed in chronological order, since there has to be some order, and I thought following this would prove faci^ le for me, but I lose the thread, digress or remember something important several pages ahead and there is no way to fit it in anymore. My memory moves through circles, spirals and trapeze acrobatics.

I am Maya Vidal, nineteen years old, female sex, unmarried, without a lover for lack of opportunity and not because I am squeamish, born in Berkeley, California, U.S. passport, temporary refugee on an island in the South. I was named Maya because my Nini has a passion for India and because my parents could think of no other name, despite having had nine months to think of it. In Hindi maya means "spell, illusion, dream." Nothing to do with my character. Attilla would suit me better, because where I pass I leave only scorched earth.

My story begins in Chile with my grandmother, my Nini, long before I was born, because if she had not emigrated abroad, she would not have fallen in love with my Popó or settled in California, my father would not have met my mother, and I would not be me but a very different Chilean girl.

What do I look like? Six feet, fifty-eight pounds, muscular legs, clumsy hands, blue or gray eyes, depending on the time of day, probably blond, but I am not sure since I have not seen the natural color of my hair for several years. I did not inherit my grandmother's exotic look, with her olive skin and those dark circles under the eyes giving a dissolute air, nor that of my father, eJegant as a bullfighter and just as vain; I do not even resemble my grandfather,my magnificent Popò, unfortunately not my biological progenitor but my Nini's second husband.

I resemble my mother, at least in build and skin color, a princess from Lapland, as I believed before I had the use of reason, but a Danish stewardess with whom father, a pilot, fell in love in the air. He was too young to marry, but he got it into his head that this was the woman of his life and doggedly pursued her until she accepted out of exhaustion. Or maybe because she was pregnant. The fact is that they regretted it after less than a week.... A few days later when her husband was in the air, my mother packed her bags,and took a cab. My Nini was out and about in San Francisco campaigning against the Gulf War, but my Popò found the bundle she handed him without any explanation,before rushing into the cab that was waiting for her.

The granddaughter was so light that she fit in one of her grandfather's hands. Shortly thereafter the Danish princess mailed the divorce papers and while she was at it, the relinquishment of custody of her daughter. My mother's name is Marta Otter and I met her the summer I was eight years old, when my grandparents took me to Denmark.

I am in Chile, the country of my grandmother Nidia Vidal, where the ocean eats up the land in bites and the South American continent crumbles into islands. To be precise, I am in Chiloé, in the region of Los Lagos, between parallel 41 and 43, southern latitude, an archipelago of about nine thousand square kilometers in area and more or less two hundred thousand inhabitants, all of them shorter than me. In Mapudungun, the language of the region's indigenous people, Chiloé means land of the cahuiles, the shrill-voiced, black-headed seagulls, but it should have been called land of wood and potatoes. Besides Isla Grande, where the most populous towns are located, there are many small islands, several of them uninhabited. Some form small groups of three or four and are so close to each other that at low tide they are connected by land, but I was not fortunate enough to end up on one of them-I live forty-five minutes by motor launch, in calm seas, from the nearest town.

My journey from Northern California to Chiloé began in my grandmother's noble yellow Volkswagen, which has had seventeen accidents since 1999 but runs like a Ferrari. I left in the middle of winter, on one of those windy, rainy days when San Francisco Bay loses its colors, and the landscape seems drawn with the pen, white, black,! gray. Grandma was driving in her own style, sobbing, clinging to the steering wheel like a life preserver, her eyes nailed on me more than on the road, intent on giving me final instructions. He had not yet explained exactly where he was sending me; Chile had been the only word he had said to me when he had designed the plan to make me disappear. In the car, he revealed the details and handed me a small economy edition travel guide.

"Chiloé? What kind of place is this?" I asked her. "There's all the information you need there," she said, pointing to the book.

"It seems pretty far away..."

"The farther away the better. In Chiloé I have a good friend, Manuel Arias, the only person in the world, besides Mike Kelly, whom I can ask to keep you hidden for one or years. "

"One or two years? Are you crazy, Nini?"

"Look, little girl, there are times when you don't have the slightest control over your life, things just happen, and this is just one of those times," he announced to me with his face glued to the windshield, trying to get his bearings as we traveled blindly through the tangle of highways, arrived just in time at the airport and parted without much fuss; the last image I keep is the Volkswagen jerking away in the rain. I traveled for several hours to Dallas, pressed between the window a fat one that tasted like roasted peanuts, and then on a plane, which would drop me off in Santiago ten hours later I was hungry, in the grip of memories, thoughts, and immersed in reading the book about Chiloé, which extolled the beauty of the wooden churches and rural life.

Suddenly there appeared a green valley, sown fields and in the distance Santiago, where my grandmother and father were born and where a piece of my family history lives.

Of my grandmother's past, she rarely talks about it, as if her life began only when she met my Popó. In 1974, her first husband, Felipe Vidal, died in Chile, a few months after the military coup that brought down the socialist government of Salvatore Allende and established a dictatorship in the country. Widowed, she decided she did not want to live under an oppressive regime and emigrated to Canada with her son Andrés, my father. He could not add much to this tale because he remembers little of his childhood, but he still reveres his father, of whom only three photographs have survived. "We're never coming back, are we?" commented Andrés on the plane taking him to Canada. It was not a question, but an accusation. He was nine years old, had suddenly matured in recent months, and demanded explanations as he realized that his mother was trying to protect him with half-truths and half-lies. He had accepted with fortitude the news of his father's sudden heart attack and the fact that he had been buried without being allowed to see the body and take leave of him. Shortly thereafter he had found himself on a plane bound for Canada. "Of course we will come back, Andrés," his mother had assured him, but he had not believed her.

In Toronto they had been taken in by volunteers from the Refugee Committee, who supplied them with adequate clothing and placed them in a furnished apartment, with beds made and a full refrigerator. For the first three days, as long as the supplies lasted, mother and son remained cooped up, shivering with loneliness, but on the fourth day a social worker who spoke unobtrusive Spanish appeared to inform them of the benefits and rights of any resident of Canada. First they received intensive English lessons and the child !u enrolled in school in the class that corresponded to him; then Nidi| managed to get a job as a driver to avoid the humiliation of receiving handouts from the state without working.

The short Canadian autumn gave way to a polar winter, wonderful for Andrés, now called Andy, who discovered the joy of ice skating and skiing, but unbearable for Nidia, who could not find warmth Ine to overcome the sadness of losing her husband and her country. Her mood did not improve with the arrival of an uncertain spring nor with the flowers, which sprouted as if by magic in a single night where before there was a hard layer of snow. She felt rootless and kept her suitcase packed, tense about the opportunity to return to Chile as soon as the dictatorship was over, unable to imagine that it would last sixteen years.

Nidia Vidal stayed in Toronto for a couple of years, counting the days and hours, until she met Paul Ditson II, my Popo, a UC Berkeley professor who was also in Toronto to give a series of lectures on an elusive planet whose existence she was trying to prove through poetic calculations and leaps of imagination. My Popó, one of the first African American astronomers to practice a profession in which the overwhelming majority was white, was an eminence in his field, author of several books.

By one of those novel-like coincidences he had ended his visit to Chile on the same day in 1974 that she had left with her son for Canada. I came to think that it could very well be that, without knowing each other, they had been near each other at the airport, waiting for their respective flights, but according to them that was not possible, because he would have noticed that beautiful woman and she would have seen him, too, because a black man drew attention in Chile at that time, especially if he was as tall and elegant as my Popó.

All it took for Nidia was one morning of driving around Toronto with her passenger to realize that she possessed the rare combination of a brilliant mind with a dreamer's imagination and a total lack of practical sense, which she instead boasted of possessing in abundance. My Nini could never explain to me how she arrived at such a conclusion from behind the wheel of the car and in the midst of chaotic traffic, but the fact is that she got it right. The astronomer seemed lost co me the planet he was looking for in the cycle; he could calculate in less than a blink of an eye how long it takes a spacecraft to get to the moon traveling at 28,286 kilometers per hour, but he was puzzled by an electric coffee maker. It had been years since she had felt the vague flutter of love's wings, and that man, very different from the others she had known in her thirty-three years, intrigued and attracted her.

Even my Popó, rather frightened by the recklessness with which his driver was driving, felt curiosity for the woman hiding behind an oversized uniform. He was not a man to give in easily to sentimental impulses, and if the idea of seducing her ever crossed his mind, he discarded it immediately as if it were a nuisance. Instead, my Nini, who had nothing to lose decided to openly confront the astronomer.

Hace una semana, en el aeropuerto de San Francisco, mi abuela me abrazó sin llorar y me repitió que, si me importaba mi existencia, no me pusiera en contacto con nadie hasta estar seguros de que mis enemigos ya no me buscaban. Mi Nini es paranoica, como toda la gente de la República Popular Independiente de Berkeley, perseguida por el gobierno y extra-ri, pero en mi caso no exageraba: cualquier prevención no estaría de más. Me entregó un cuaderno con cien páginas para que llevara un diario de mi vida, como había hecho desde los ocho hasta los quince años, cuando el destino aún no me había dado la espalda. "Ya tendrás tiempo para ti, Maya. Aprovecha para escribir sobre el enorme disparate que has cometido, quizá así te des cuenta de su magnitud", me dijo.

Para no ofenderla, metí el cuaderno en la mochila, pero no tenía intención de utilizarlo, aunque aquí, efectivamente, el tiempo se diluye y escribir es una forma de ocuparlo. Esta primera semana de exilio ha sido larga para mí. Me encuentro en una pequeña isla casi invisible en el mapa, caído en plena Edad Media. Me resulta complicado escribir sobre mi vida, porque no distingo entre los recuerdos y lo que es producto de mi imaginación; la pura verdad puede resultar tediosa, y por eso, sin darme cuenta, la edito o enfatizo, aunque me he propuesto corregir este defecto y mentir lo menos posible en el futuro. Y así es como ahora, cuando hasta los yanomamis amazónicos usan ordenadores, me encuentro escribiendo a mano. Avanzo despacio y mi letra parece cirílica, ya que ni siquiera yo puedo descifrarla, pero imagino que página tras página empezará a mejorar. Escribir es como montar en bicicleta: no se olvida, por muchos años que pasen sin practicar. Intento proceder por orden cronológico, ya que tiene que haber algún orden, y pensé que seguirlo me resultaría faci^ le, pero pierdo el hilo, divago o recuerdo algo importante varias páginas más adelante y ya no hay manera de encajarlo. Mi memoria se mueve en círculos, espirales y acrobacias trapecistas.

Soy Maya Vidal, diecinueve años, sexo femenino, soltera, sin amante por falta de oportunidades y no porque sea remilgada, nacida en Berkeley, California, pasaporte estadounidense, refugiada temporal en una isla del Sur. Me pusieron Maya porque a mi Nini le apasiona la India y porque a mis padres no se les ocurrió otro nombre, a pesar de haber tenido nueve meses para pensarlo. En hindi maya significa "hechizo, ilusión, sueño". Nada que ver con mi carácter. Attilla me iría mejor, porque por donde paso sólo dejo tierra quemada.

Mi historia comienza en Chile con mi abuela, mi Nini, mucho antes de que yo naciera, porque si ella no hubiera emigrado al extranjero, no se habría enamorado de mi Popó ni se habría instalado en California, mi padre no habría conocido a mi madre y yo no sería yo, sino una chilena muy distinta.

¿Qué aspecto tengo? Un metro ochenta, cincuenta y ocho kilos, piernas musculosas, manos torpes, ojos azules o grises, según la hora del día, probablemente rubia, pero no estoy segura ya que hace varios años que no veo el color natural de mi pelo. No heredé el aspecto exótico de mi abuela, con su piel aceitunada y esas ojeras que le daban un aire disoluto, ni el de mi padre, eJegante como un torero e igual de vanidoso; ni siquiera me parezco a mi abuelo,mi magnífico Popò, por desgracia no mi progenitor biológico sino el segundo marido de mi Nini.

Me parezco a mi madre, al menos en complexión y color de piel, una princesa de Laponia, como creía antes de tener uso de razón, pero una azafata danesa de la que padre, piloto, se enamoró en el aire. Era demasiado joven para casarse, pero se le metió en la cabeza que aquella era la mujer de su vida y la persiguió tenazmente hasta que ella aceptó por agotamiento. O tal vez porque estaba embarazada. El caso es que se arrepintieron al cabo de menos de una semana.... Unos días después, cuando su marido estaba en el aire, mi madre hizo las maletas y cogió un taxi. Mi Nini estaba por San Francisco haciendo campaña contra la guerra del Golfo, pero mi Popò encontró el paquete que ella le entregó sin ninguna explicación,antes de meterse corriendo en el taxi que la esperaba.

La nieta era tan ligera que cabía en una de las manos de su abuelo. Poco después, la princesa danesa envió por correo los papeles del divorcio y, de paso, la renuncia a la custodia de su hija. Mi madre se llama Marta Otter y la conocí el verano en que tenía ocho años, cuando mis abuelos me llevaron a Dinamarca.

Estoy en Chile, el país de mi abuela Nidia Vidal, donde el océano se come la tierra a bocados y el continente sudamericano se desmorona en islas. Para ser precisos, estoy en Chiloé, en la región de Los Lagos, entre los paralelos 41 y 43, latitud sur, un archipiélago de unos nueve mil kilómetros cuadrados de superficie y más o menos doscientos mil habitantes, todos ellos más bajos que yo. En mapudungun, la lengua de los indígenas de la región, Chiloé significa tierra de los cahuiles, las gaviotas de voz chillona y cabeza negra, pero debería haberse llamado tierra de madera y papas. Además de la Isla Grande, donde se encuentran los pueblos más poblados, hay muchas islas pequeñas, varias de ellas deshabitadas. Algunas forman pequeños grupos de tres o cuatro y están tan cerca unas de otras que en marea baja están conectadas por tierra, pero yo no tuve la suerte de acabar en una de ellas: vivo a cuarenta y cinco minutos en lancha motora, con mar en calma, de la ciudad más cercana.

Mi viaje desde el norte de California a Chiloé comenzó en el noble Volkswagen amarillo de mi abuela, que ha tenido diecisiete accidentes desde 1999 pero funciona como un Ferrari. Partí en pleno invierno, en uno de esos días ventosos y lluviosos en que la bahía de San Francisco pierde sus colores, y el paisaje parece dibujado con el bolígrafo, ¡blanco, negro, gris! La abuela conducía a su estilo, sollozando, aferrada al volante como a un salvavidas, con los ojos clavados en mí más que en la carretera, empeñada en darme las últimas instrucciones. Aún no me había explicado exactamente adónde me enviaba; Chile había sido la única palabra que me había dicho cuando diseñó el plan para hacerme desaparecer. En el coche, me reveló los detalles y me entregó una pequeña guía de viajes de edición económica.

"¿Chiloé? ¿Qué clase de lugar es éste?". le pregunté. "Ahí está toda la información que necesitas", dijo señalando el libro.

"Parece bastante lejos...".

"Mientras más lejos, mejor. En Chiloé tengo un buen amigo, Manuel Arias, la única persona en el mundo, además de Mike Kelly, a quien puedo pedir que te mantenga oculto durante uno o varios años. "

"¿Uno o dos años? ¿Estás loca, Nini?"

"Mira, pequeña, hay veces que no tienes el más mínimo control sobre tu vida, las cosas simplemente suceden, y ésta es sólo una de esas veces", me anunció con la cara pegada al parabrisas, intentando orientarse mientras viajábamos a ciegas por la maraña de autopistas, llegábamos justo a tiempo al aeropuerto y nos separábamos sin mucho alboroto; la última imagen que conservo es la del Volkswagen alejándose a sacudidas bajo la lluvia. Viajé varias horas hasta Dallas, apretujado entre la ventanilla una gorda que sabía a cacahuetes tostados, y luego en un avión, que me dejaría en Santiago diez horas después Tenía hambre, me atenazaban los recuerdos, los pensamientos, y estaba inmerso en la lectura del libro sobre Chiloé, que ensalzaba la belleza de las iglesias de madera y la vida rural.

De pronto apareció un valle verde, campos sembrados y a lo lejos Santiago, donde nacieron mi abuela y mi padre y donde vive un pedazo de mi historia familiar.

Del pasado de mi abuela, rara vez habla, como si su vida empezara sólo cuando conoció a mi Popó. En 1974, su primer marido, Felipe Vidal, murió en Chile, pocos meses después del golpe militar que derrocó al gobierno socialista de Salvatore Allende e instauró una dictadura en el país. Viuda, decidió que no quería vivir bajo un régimen opresivo y emigró a Canadá con su hijo Andrés, mi padre. No pudo añadir mucho a este relato porque recuerda poco de su infancia, pero sigue venerando a su padre, del que sólo se conservan tres fotografías. "No volveremos nunca, ¿verdad?", comentó Andrés en el avión que le llevaba a Canadá. No era una pregunta, sino una acusación. Tenía nueve años, había madurado repentinamente en los últimos meses y exigía explicaciones al darse cuenta de que su madre trataba de protegerle con medias verdades y medias mentiras. Había aceptado con entereza la noticia del repentino infarto de su padre y el hecho de que lo hubieran enterrado sin permitirle ver el cadáver y despedirse de él. Poco después se había encontrado en un avión con destino a Canadá. "Claro que volveremos, Andrés", le había asegurado su madre, pero él no la había creído.

En Toronto habían sido acogidos por voluntarios del Comité de Refugiados, que les proporcionaron ropa adecuada y los instalaron en un apartamento amueblado, con las camas hechas y el frigorífico lleno. Durante los tres primeros días, lo que duraron las provisiones, madre e hijo permanecieron encerrados, tiritando de soledad, pero al cuarto día apareció una trabajadora social que hablaba un español discreto para informarles de las prestaciones y derechos de cualquier residente en Canadá. Primero recibieron clases intensivas de inglés y el niño !u matriculó en el colegio en la clase que le correspondía; luego Nidi| consiguió un trabajo como conductor para evitar la humillación de recibir limosnas del Estado sin trabajar.

El corto otoño canadiense dio paso a un invierno polar, maravilloso para Andrés, ahora llamado Andy, que descubrió la alegría del patinaje sobre hielo y del esquí, pero insoportable para Nidia, que no encontraba calor Ine para superar la tristeza de perder a su marido y a su país. Su ánimo no mejoró con la llegada de una primavera incierta ni con las flores, que brotaron como por arte de magia en una sola noche donde antes había una dura capa de nieve. Se sentía desarraigada y guardaba la maleta, tensa ante la oportunidad de volver a Chile en cuanto terminara la dictadura, incapaz de imaginar que duraría dieciséis años.

Nidia Vidal se quedó en Toronto un par de años, contando los días y las horas, hasta que conoció a Paul Ditson II, mi Popó, un profesor de la Universidad de Berkeley que también estaba en Toronto para dar una serie de conferencias sobre un planeta esquivo cuya existencia intentaba demostrar mediante cálculos poéticos y saltos de imaginación. Mi Popó, uno de los primeros astrónomos afroamericanos en ejercer una profesión en la que la inmensa mayoría eran blancos, era una eminencia en su campo, autor de varios libros.

Por una de esas casualidades de novela, había terminado su visita a Chile el mismo día de 1974 en que ella había partido con su hijo hacia Canadá. Llegué a pensar que bien podría ser que, sin conocerse, hubieran estado cerca el uno del otro en el aeropuerto, esperando sus respectivos vuelos, pero según ellos eso no era posible, porque él se habría fijado en esa hermosa mujer y ella también lo habría visto a él, porque un negro llamaba la atención en Chile en esa época, sobre todo si era tan alto y elegante como mi Popó.

A Nidia le bastó una mañana de paseo por Toronto con su pasajero para darse cuenta de que poseía la rara combinación de una mente brillante con imaginación de soñadora y una total falta de sentido práctico, que en cambio se jactaba de poseer en abundancia. Mi Nini nunca pudo explicarme cómo llegó a semejante conclusión al volante del coche y en medio de un tráfico caótico, pero el caso es que acertó. El astrónomo parecía perdido co me el planeta que buscaba en el ciclo; podía calcular en menos de un pestañeo cuánto tarda una nave espacial en llegar a la Luna viajando a 28.286 kilómetros por hora, pero le desconcertaba una cafetera eléctrica. Hacía años que no sentía el vago aleteo de las alas del amor, y aquel hombre, muy distinto a los demás que había conocido en sus treinta y tres años, la intrigaba y atraía.

Incluso mi Popó, bastante asustado por la temeridad con que conducía su chófer, sintió curiosidad por la mujer que se ocultaba tras un uniforme demasiado grande. No era un hombre que cediera fácilmente a los impulsos sentimentales, y si alguna vez se le pasaba por la cabeza la idea de seducirla, la desechaba inmediatamente como si fuera una molestia. En cambio, mi Nini, que no tenía nada que perder decidió enfrentarse abiertamente al astrónomo.

Source images / Fuente imágenes: Isabel Allende Official Website / Sitio Oficial.

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks!