For all of us who have spent our lives defending free software, public schools, free universities and other such things, the advent of OpenOffice as an alternative to Microsoft's Office was something of an IT miracle.

The monopoly exercised by the house of Richmond through all its products and operating systems had the effect of unleashing, from this side of the barricade, a natural and profound antipathy. Office - at that time the flagship product of Windows, managed by a certain Bill Gates - was the devil incarnate. No more, no less.

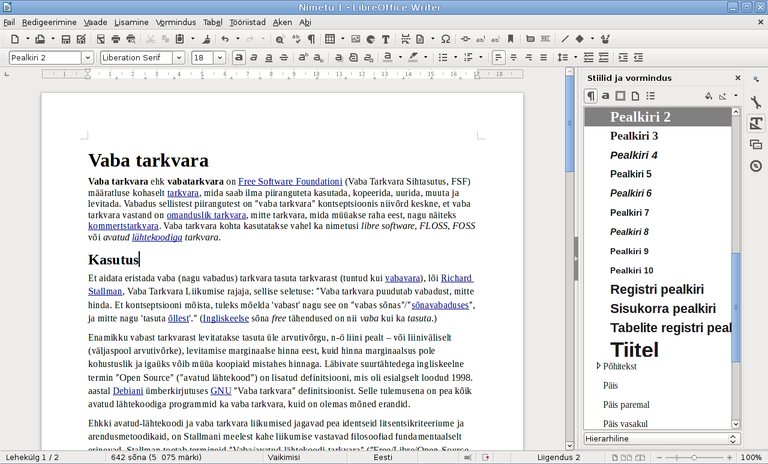

I remember the first thing I noticed in OpenOffice Writer was that you could automatically transform all documents into .pdf with the push of a button. Fantastic. Office Word - as a good market monopolist - lacked this feature and was only accessible through paid programs such as Acrobat Reader. Over time some things changed, others did not.

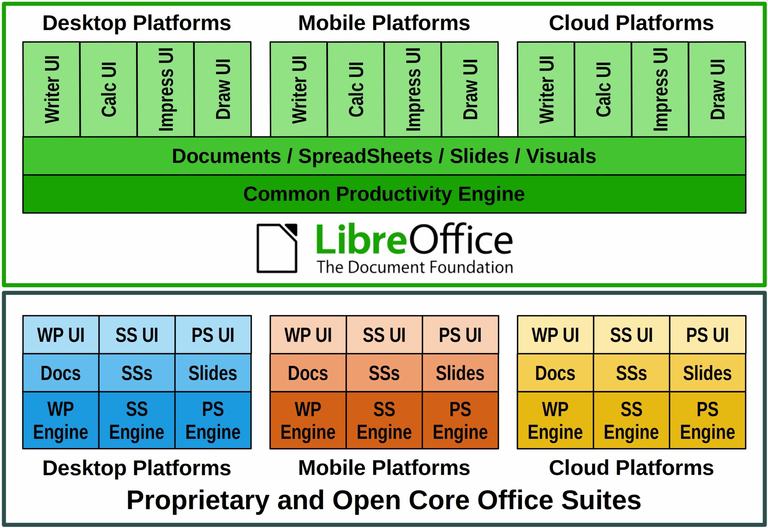

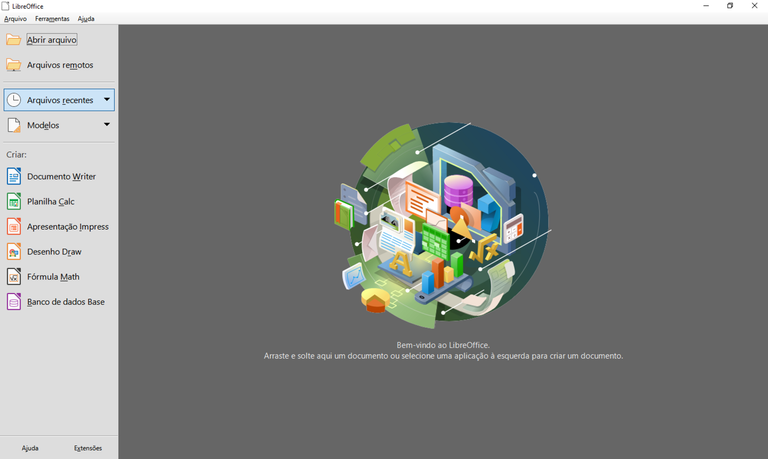

In the meantime Oracle left the original project, Apache took over and everything seemed to indicate that the end of a beautiful cycle had come. Some developers ran out and created LibreOffice, a true clone of OpenOffice, and made it the default in (almost) all Linux applications.

But this whole story deserves more than a few paragraphs, some ironic and some much less, and today I want to tell you step by step how this project, which fortunately still stands, developed.

And it is precisely with OpenOffice Writer that I am writing this post.

A bit of history in the evolution of OpenOffice.

OpenOffice, the most famous free office suite, has recently reached version 4.1.14 and getting there has not been an easy journey.

Apache OpenOffice is the result of more than twenty years of work. Designed from the outset as a single program, it offers a consistency that other products cannot match. A completely open development process means that everyone can report bugs, ask for new features or improve the program. The result: Apache OpenOffice does everything you need your office software to do, the way you want it to do it.

To understand how OpenOffice has evolved into its current form, you have to look at the past.

We have to go back to the 1980s and 1990s, to the time when an American computer giant was faced with the need to provide its employees with an Office-like suite for machines that didn't run Windows?

When Linux didn't exist, Sun was king.

In 1982, almost ten years before Linux saw the light of day, Sun Microsystems created its first UNIX-based workstation, the Sun-1. Its operating system, called SunOS, later became Solaris. It was one of the ‘great-uncles’ of Linux.

SunOS 3.5, the system on Sun computers in 1988 (source)

Sun's workstations, very powerful for the time, lacked office utilities such as Microsoft Office, which only ran on DOS or Mac OS systems. At the time, SunOS / Solaris only had WordPerfect and little else.

WordPerfect running on a NeXT machine (source)

In 1999, Sun Microsystems had over forty thousand employees who, in addition to using Solaris workstations, had Windows machines to perform tasks as simple as writing reports or updating spreadsheets.

To avoid spending money on tens of thousands of Office licenses, Sun bought a small German company, Star Division, which had created its own office suite for OS/2 Warp, Windows, Linux and, of course, Solaris. That suite was called StarOffice.

It was a masterstroke, but not surprising: already in 1992, Andreas von Bechtolsheim, one of the co-founders of Sun Microsystems, had bought 20% of Star Division. When StarOffice reached maturity, Sun brought out the briefcase with the money.

The Office that came from Hamburg (1992-1999).

Star Division was a little-known German company, one of those that form the basis of the Teutonic economy. In 1999, when Sun paid almost 60 million dollars for it, Star Division was already developing its own cross-platform office suite, StarOffice.

The person behind StarOffice was Marco Börries, a German who was only sixteen years old when, in 1984, he founded his own company. His goal was to be the Bill Gates of Lower Saxony.

It was achievable. In the German market, which was much more diversified and sophisticated than others, it was not uncommon for productivity utilities for machines such as the Commodore 64 or the Amstrad CPC, which in other countries were limited to video games, to be a sales success.

Star Writer, Star Division's first program, was a simple word processor for the Amstrad CPC. It did the bare minimum, but it was a million-mark hit. With that money, Marco Börries bought his father a Mercedes to apologise for the inconvenience of using the garage at home as the company's headquarters.

Star Writer, the first Star Division programme (source)

In the early nineties, Star Division radically changed its paradigm. Its code was modernised and its programs were adapted to run on the main operating systems of the time. In 1992, Star Division released StarOffice 1.0 for MS-DOS.

In 1995, Star Division introduced the first cross-platform office suite in history, StarOffice 3.0, compatible with DOS, Windows, OS/2 and Solaris. It included a word processor, a spreadsheet and a vector drawing program.

For Sun, which had been closely monitoring Star Division's moves since the early 1990s, StarOffice was a dream come true, compatible with its UNIX-oriented business vision of working on local area networks and the Internet.

Sun buys StarOffice... and releases it! (1999-2000).

In 1999, when StarOffice reached version 5.0, Sun shelled out millions of dollars to take over Star Division. Marco Börries and the few hundred employees of the German company went to work for Sun for a short time.

Sun Microsystems' plan at the time was similar to that of other companies during the .com Bubble: to conquer the Internet. Their vision for StarOffice was an office suite ‘distributed over the Internet’ to ‘change the rules of the game’.

In 1999, Sun spoke enthusiastically of a ‘StarOffice revolution’.

A year later the bubble burst, and in one of the most important moves in the history of software, Sun decided to release the OpenOffice source code so that the community could develop the suite Linux-style.

In the words of Marco Börries, this was ‘the greatest contribution in the history of free software’. Version 1.0 had more than 7.5 million lines of code, a hitherto unprecedented amount, so much so that some doubted Sun's intentions.

Para todos aquellos que nos hemos pasado la vida defendiendo el software libre, la escuela pública, la universidad gratuita y otras yerbas como se diría en mi país, el advenimiento de OpenOffice como alternativa a Office de Microsoft fue algo así como un milagro informático.

El monopolio ejercido por la casa de Richmond a través de todos sus productos y sistemas operativos logró el efecto de desatar, de esta parte de la barricada, una natural y profunda antiapatía. Office -en esos momentos el producto de punta de casa Windows, administrada por un tal Bill Gates, encarnaba al diablo. Ni más ni menos.

Recuerdo que la primera cosa que noté en OpenOffice Writer fue que se podían transformar automátiucamente todos los documentos en .pdf con solo apretar un pulsante. Fantástico. Office Word -como buen monopolista de mercado, carecía de esa función y solo se podía acceder a ella a través de programas de pago como Acrobat Reader. Con el tiempo algunas cosas fueron cambiando, otras no.

Mientras tanto Oracle dejó el proyecto original, se hizo cargo Apache y todo parecía indicar que había llegado el final de un hermoso ciclo. Algunos desarrolladores salieron corriendo y crearon LibreOffice, un verdadero clone de OpenOffice, y lo pusieron de defecto en (casi) todas las aplicaciones Linux.

Pero toda esta historia merece más que unos pocos párrafos, algunos irónicos y otros mucho menos, y hoy quiero contarles paso por paso como se desarrolló este proyecto que, por suerte, sigue en pie.

Y es con OpenOffice Writer precisamente que les estoy escribiendo este post.

Un poco de historia en la evolución de OpenOffice.

OpenOffice, la suite ofimática gratuita más famosa, ha alcanzado hace poco la versión 4.1.14 y llegar hasta ella no ha sido un viaje fácil.

Apache OpenOffice es el resultado de más de veinte años de trabajo. Diseñado desde el principio como un único programa, ofrece una consistencia que otros productos no pueden igualar. Un proceso de desarrollo completamente abierto significa que todos pueden reportar errores, pedir nuevas características o mejorar el programa. El resultado: Apache OpenOffice hace todo lo que usted necesita que su software de oficina haga, en la forma que usted quiere que se haga.

Para entender cómo ha evolucionado OpenOffice hasta llegar a su forma actual, hay que mirar al pasado.

Hemos de remontarnos a los años ochenta y noventa, a la época en que un gigante de la informática americano se enfrentó a la necesidad de proveer a sus empleados de una suite tipo Office para máquinas que no ejecutaban Windows...

Cuando Linux no existía, Sun era el rey.

En 1982, casi diez años antes de que Linux viera la luz, Sun Microsystems creaba su primera estación de trabajo basada en UNIX, la Sun-1. Su sistema operativo, llamado SunOS, se convirtió más tarde en Solaris. Fue uno de los "tíos-abuelos" de Linux.

SunOS 3.5, el sistema de los equipos Sun en 1988 (fuente)

Las estaciones de trabajo de Sun, muy potentes para la época, carecían de utilidades ofimáticas como las de Microsoft Office, que solo se ejecutaban en sistemas DOS o Mac OS. En aquella época, SunOS / Solaris solo contaba con WordPerfect y poco más.

WordPerfect ejecutándose en una máquina NeXT (fuente)

En 1999, Sun Microsystems tenía más de cuarenta mil empleados que, además de usar estaciones de trabajo con Solaris, tenían máquinas con Windows para efectuar tareas tan sencillas como redactar informes o actualizar hojas de cálculo.

Para no desembolsar dinero en decenas de miles de licencias de Office, Sun compró una pequeña empresa alemana, Star Division, que había creado su propia suite ofimática para OS/2 Warp, Windows, Linux y, cómo no, Solaris. Esa suite se llamaba StarOffice.

Fue un golpe magistral, pero no sorprendente: ya en 1992, Andreas von Bechtolsheim, uno de los confundadores de Sun Microsystems, había comprado un 20% de Star Division. Cuando StarOffice alcanzó la madurez, Sun sacó el maletín con el dinero.

El Office que venía de Hamburgo (1992-1999).

Star Division era una empresa alemana poco conocida, de esas que forman la base de la economía teutona. En 1999, cuando Sun desembolsó casi 60 millones de dólares por ella, Star Division ya desarrollaba su propia suite ofimática multiplataforma, StarOffice.

La persona detrás de StarOffice fue Marco Börries, un alemán que tenía solo dieciséis años cuando, en 1984, fundó su propia empresa. Su objetivo era ser el Bill Gates de la Baja Sajonia.

Era algo factible. En el mercado alemán, mucho más diversificado y sofisticado que otros, no era infrecuente que utilidades de productividad para máquinas como el Commodore 64 o el Amstrad CPC, que en otros países se limitaban a los videojuegos, fueran un éxito de ventas.

Star Writer, el primer programa de Star Division, fue un procesador de textos sencillo para Amstrad CPC. Permitía hacer lo mínimo, pero fue un éxito de un millón de marcos. Con ese dinero, Marco Börries le compró un Mercedes a su padre para disculparse por las molestias ocasionadas al usar el garaje de casa como sede de la empresa.

Star Writer, el primer programa de Star Division (fuente)

A principios de los noventa, Star Division cambió radicalmente de paradigma. Su código se modernizó y sus programas se adaptaron para funcionar en los principales sistemas operativos de la época. En 1992, Star Division lanzaba StarOffice 1.0 para MS-DOS.

En 1995, Star Division presentaba la primera suite ofimática multiplataforma de la historia, StarOffice 3.0, compatible con DOS, Windows, OS/2 y Solaris. Contaba con un procesador de textos, una hoja de cálculo y un programa de dibujo vectorial.

Para Sun, que controlaba atentamente los movimientos de Star Division desde principios de los años noventa, StarOffice era un sueño hecho realidad, compatible con su visión de negocios orientada a UNIX y al trabajo en redes de área local e Internet.

Sun compra StarOffice... ¡y lo libera! (1999-2000).

En 1999, cuando StarOffice alcanzó la versión 5.0, Sun desembolsó millones de dólares para hacerse con Star Division. Marco Börries y los pocos centenares de trabajadores de la empresa alemana pasaron a trabajar por Sun durante una corta temporada.

El plan de Sun Microsystems por aquel entonces era similar al de otras empresas durante la Burbuja .com: conquistar Internet. Su visión para StarOffice era la de una suite ofimática "distribuida a través de Internet" para "cambiar las reglas del juego".

En 1999, Sun hablaba con entusiasmo de una "revolución de StarOffice"

Un año después estalló la burbuja, y en uno de los movimientos más importantes en la historia del software, Sun decidió liberar el código fuente de OpenOffice para que la comunidad pudiese desarrollar la suite al estilo Linux.

En palabras de Marco Börries, se trataba de "la más grande contribución en la historia del software libre". La versión 1.0 tenía más de 7,5 millones de líneas de código, una cantidad hasta el momento sin precedentes, tanto que hubo quien dudó de las intenciones de Sun.

- Sources/Fuentes:

| Blogs, Sitios Web y Redes Sociales / Blogs, Webs & Social Networks | Plataformas de Contenidos/ Contents Platforms |

|---|---|

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Los Apuntes de Tux |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | El Mundo de Ubuntu |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Nel Regno di Linux |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Linuxlandit & The Conqueror Worm |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Pianeta Ubuntu |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Re Ubuntu |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Nel Regno di Ubuntu |

| Red Social Twitter / Twitter Social Network | @hugorep |

| Blurt Official | Blurt.one | BeBlurt | Blurt Buzz |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|---|

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks @ctime!