En el ajedrez ha habido rivalidades que han hecho historia. Sobre todo porque este deporte, tan difundido en la ex-URSS que ha dado tantos notables campeones, normalmente ha sido contrapuesto con estructuras políticas antagónicas: por un lado los ajedrecistas que representaban la ex-URSS por una parte -sinónimo de comunismo-, y aquellos disidentes, exiliados y ajedecristas del llamado "mundo capitalista", especialmente de los EE. UU. -sinónimo de capitalismo-

Las dos doctrinas político-económicas contrapuestas, y rivales antagónicos durante décadas no ecnontraron mejor modo de expresarse que en el ajedrez.

La rivalidad entre Bobby Fisher y Boris Spassky representante del establishment ruso es legendaria a punto tal que las excentricidaes y exageradas exigencias de Fisher lo llevan a perder la corona al negarse a disputarla ante Anayoly Karpov en 1975

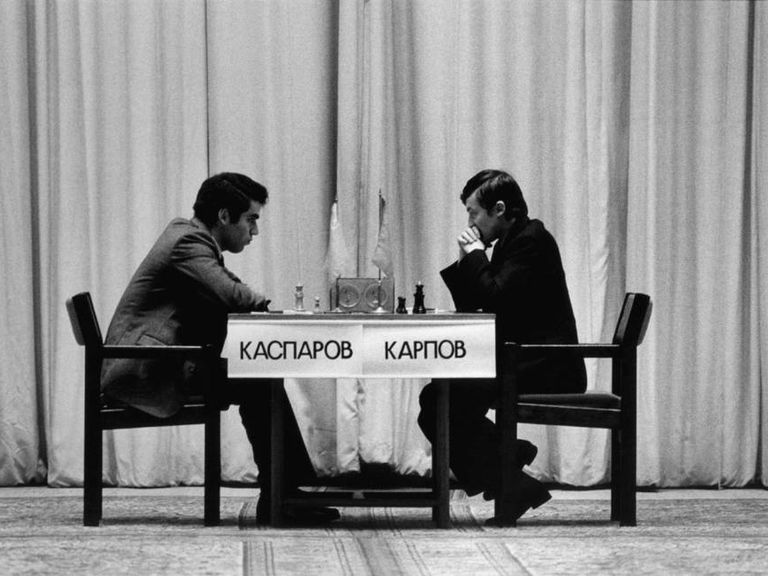

La misma rivalidad años más tarde enfrentaría a Garry Kasparov y Anatoly Karpov.

El primero representaba la nueva linea "revolucionaria y contestataria" que más tarde se consolidaría con la llamada perestroika, llevada a cabo por el primer ministro Mijaíl Gorbachov y que suponía sacar a la economía soviética del caos y el estancamiento en el que estaba sumida y que provocó la disolución de la URSS como tal y el fin de la llamada guerra fría contra los EE. UU.

Karpov era el burócrata que representaba lo más clásico del politburó ruso. Dueñ de un estilo conservador constrastaba notablemente con la agresividad de Kasparov.

En esos momentos el rival de Karpov, el americano Bobby Fischer, se negó a defender su título, por lo que en éste había pasado directamente al soviético.

La fama de rebelde.

La fama de rebelde de Kasparov inicia con el primer match que disputa con Karpov. Un match increíble, histórico que ha entrado en los anales del ajedrez mundial.

Las primera 9 partidas le dan a Karpov una supremacía totaly absoluta sobre su rival. Una verdadera paliza. Cuatro a cero. Cuatro victorias para Karpov y cinco tablas. El astro rey le estaba dando una lección a la estrella naciente.

Cuando en 1985 Kasparov y Karpov se enfrentaron en Moscú, se trataba de su segundo match pero el primero, celebrado un año antes, nunca había llegado a terminarse. Aquel encuentro inicial entre “las dos K”, como se les suele denominar, había resultado uno de los más extraños de cualquier competición ajedrecística de la historia. En las primeras nueve partidas, Karpov estaba propinando una paliza sin paliativos a su joven rival: le derrotaba por cuatro victorias a cero (otras cinco partidas fueron tablas), y sólo necesitaba dos más para revalidar su título. Parecía que las alas que habían elevado a Kasparov hasta casi tocar el cielo ajedrecístico se habían fundido con facilidad en cuanto se encontró demasiado cerca de ser el astro rey.

Sin embargo a partir de la décima partida ocurre un hecho insólito. Kasparov decide no perder y comienza a adoptar estrategias de defensa más que de ataque tratando de minear la resistencia (física y anímica de su rival). Y lo logra. Obtiene diecisiete tablas seguidas! Diecisiete partidas en las cuales Karpov no logró doblegar a su rival.

Fue el inicio del fin. Karpov logra otra victoria en la partida 17a pero es la última. El esfuerzo físico (llevaban 5 meses jugando) es demasiado. No vuelve a ganar. Kasparov gana 3 partidas y consigue varias tablas. Van por la partida número 48a y la Federación Internacional de Ajedrez al ver el declino notorio a esta altura de Karpov decide de suspender el match aduciendo que Karpov había perdido 10 kgs de peso y su salud corría peligro.

Kasparov montó en cólera y aquí nació su fama de rebelde acusando a la Federación de haber salvado a Karpov de una derrota segura.

Lo dice sin eufemismos en su libro autobiográfico Kasparov: “No me excuso por comparar la mafia del ajedrez que rodeaba a Karpov con la burocracia que floreció al final de la época de Brezhnev, que se asía ciegamente a su poder y privilegios"

Su ruptura con el regimen en inmimente e inevitable.

La reanudación del match.

Kasparov con su lucha y sus denuncias logró que la Federación convocara a un nuevo match el año siguiente. Y en su segunda oportunidad Kasparov no falló.

El final era a 24 partidas como máximo para evitar los problemas del match anterior.

Kasparov ganó 13 a 11 y se proclamó nuevo campeón mundial de ajedrez.

Se convertía así en el campeón más joven de la historia y uno de los más celebrados.

Y, en algunos casos, se lo llegó a comparar con el genial y excéntrico Bobby Fischer.

Pero, a diferencia del nortemericano, Kasparov tenía unos intereses más amplios y se dedicó a la política participando en diferentes partidos de signo liberal llegando incluso en 2007 a presentar su candidatura a la presidencia de la URSS, disputándosela a Vladimir Putin, con el que siempre ha sido muy crítico.

Como le ha sucedido a muchos contrincantes del actual premier ruso tuvo que optar entre las persecuciones y la cárcel o el exilio.

Optó por el segundo luego de varias detenciones, agresiones, trabas, dificultades y amenazas a su propia familia.

Primero se radicó en Croacia donde obtiene el pasaporte. Luego recala en los EE. UU donde todavía reside.

Sus aspiraciones, sin embargo, fueron objeto de todo tipo de trabas y dificultades, incluidas agresiones y detenciones al participar en manifestaciones. Sus continuos ataques a Putin parecían poner en riesgo su seguridad y Kasparov pidió el pasaporte en Croacia.

Ha escrito un libro El invierno está llegando con un revelador subtítulo Por qué hay que parar a Vladimir Putin y a los enemigos del mundo libre.

Su lucha continúa. Ha cambiado solo los tableros. Los del ajedrez por los de la política.

In chess there have been rivalries that have made history. Above all because this sport, so widespread in the former USSR, which has produced so many notable champions, has usually been set against antagonistic political structures: on the one hand the chess players representing the former USSR on the one hand - synonymous with communism - and those dissidents, exiles and chess players from the so-called "capitalist world", especially from the USA - synonymous with capitalism - on the other. -synonymous with capitalism-.

The two opposing political-economic doctrines, and antagonistic rivals for decades, found no better way to express themselves than in chess.

The rivalry between Bobby Fisher and Boris Spassky, representative of the Russian establishment, is legendary to the point that Fisher's eccentricities and exaggerated demands led him to lose the crown when he refused to dispute it against Anayoly Karpov in 1975.

The same rivalry years later would pit Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov against each other.

The former represented the new "revolutionary and contentious" line that would later be consolidated with the so-called perestroika, carried out by Prime Minister Mikhail Gorbachev and which was supposed to bring the Soviet economy out of the chaos and stagnation in which it was mired and which led to the dissolution of the USSR as such and the end of the so-called cold war against the USA.

Karpov was the bureaucrat who represented the most classical of the Russian politburo. His conservative style contrasted sharply with Kasparov's aggressiveness.

At that time Karpov's rival, the American Bobby Fischer, refused to defend his title, so he had passed directly to the Soviet.

Kasparov's reputation as a rebel.

Kasparov's reputation as a rebel began with the first match he played against Karpov. An incredible, historic match that has entered the annals of world chess.

The first 9 games give Karpov a total and absolute supremacy over his rival. A real thrashing. Four to zero. Four wins for Karpov and five draws. The rising star was giving a lesson to the rising star.

When Kasparov and Karpov met in Moscow in 1985, it was their second match, but the first, held a year earlier, had never been completed. That initial encounter between "the two Ks", as they are often called, had turned out to be one of the strangest of any chess competition in history. In the first nine games, Karpov had been beating his young rival unchallenged: he had beaten him four games to nil (five other games were draws), and needed only two more to retain his title. It seemed that the wings that had lifted Kasparov to almost touch the chess sky had easily melted away as soon as he was too close to being king of the sun.

However, from the tenth game onwards an unusual event occurred. Kasparov decided not to lose and began to adopt strategies of defence rather than attack, trying to undermine his opponent's resistance (physical and emotional). And he succeeds. He obtained seventeen draws in a row! Seventeen games in which Karpov failed to break his opponent.

It was the beginning of the end. Karpov achieves another victory in the 17th game, but it is the last one. The physical effort (they had been playing for 5 months) was too much. He did not win again. Kasparov wins 3 games and gets several draws. They were in the 48th game and the International Chess Federation, seeing Karpov's noticeable decline at this stage, decided to suspend the match on the grounds that Karpov had lost 10 kgs of weight and his health was in danger.

Kasparov flew into a rage and his reputation as a rebel was born, accusing the Federation of having saved Karpov from certain defeat.

Kasparov puts it bluntly in his autobiographical book: "I make no apology for comparing the chess mafia that surrounded Karpov with the bureaucracy that flourished at the end of the Brezhnev era, which blindly clung to its power and privileges".

His break with the regime was immimate and unavoidable.

The resumption of the match.

Kasparov with his struggle and his denunciations succeeded in getting the Federation to call for a new match the following year. And in his second chance Kasparov did not fail.

The endgame was 24 games maximum to avoid the problems of the previous match.

Kasparov won 13-11 and was proclaimed the new world chess champion.

He thus became the youngest champion in history and one of the most celebrated.

And, in some cases, he was even compared to the brilliant and eccentric Bobby Fischer.

But, unlike the North American, Kasparov had broader interests and devoted himself to politics, participating in different liberal parties, and in 2007 he even presented his candidacy for the presidency of the USSR, contesting against Vladimir Putin, with whom he has always been very critical.

As has happened to many of the current Russian premier's opponents, he had to choose between persecution and prison or exile.

He opted for the latter after several arrests, attacks, hindrances, difficulties and threats to his own family.

He first settled in Croatia, where he obtained a passport. Then he went to the USA, where he still lives.

His aspirations, however, were met with all sorts of obstacles and difficulties, including assaults and arrests when he participated in demonstrations. His continued attacks on Putin appeared to put his safety at risk and Kasparov applied for a passport in Croatia.

He has written a book Winter is Coming with a revealing subtitle Why Vladimir Putin and the Enemies of the Free World Must Be Stopped.

His struggle continues. He has changed only the chessboards. Those of chess for those of politics.

Fuente imagen inicial / Source initial image.