He was an idol in River, Juventus and Napoli. He represented the Argentina and Italy national teams. In 1961, he won the Golden Ball. But above all, he was an excellent representative of the playful character of soccer. His sale to Italian soccer was so important in his time that with that money River completed the construction of its stadium, the mythical Monumental.

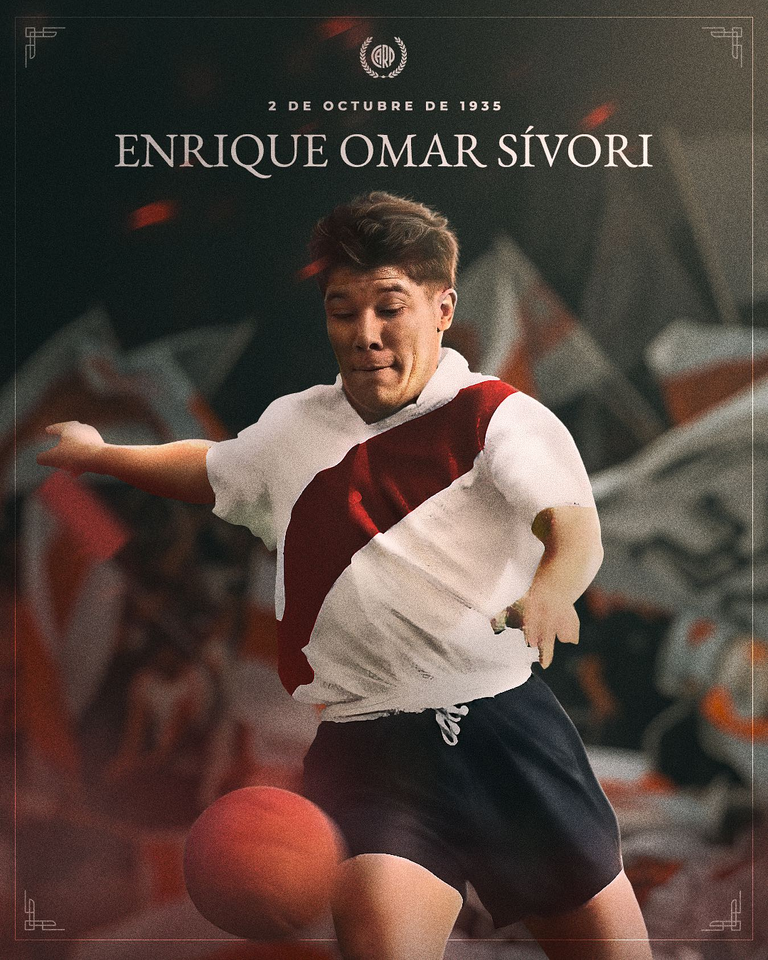

He is on everyone's lips. He is a frequent presence in every dialogue between River fans. Almost without realizing it he is there. "Let's go to the Sívori", say two fans on their way to the Monumental, who could be any other two or thousands of others who walk around, fulfilling the rite of going to see River, militating in this growing determination to fill stadiums. There is also a curiosity: most of those who mention him did not see him play. For a simple reason: they had not arrived.

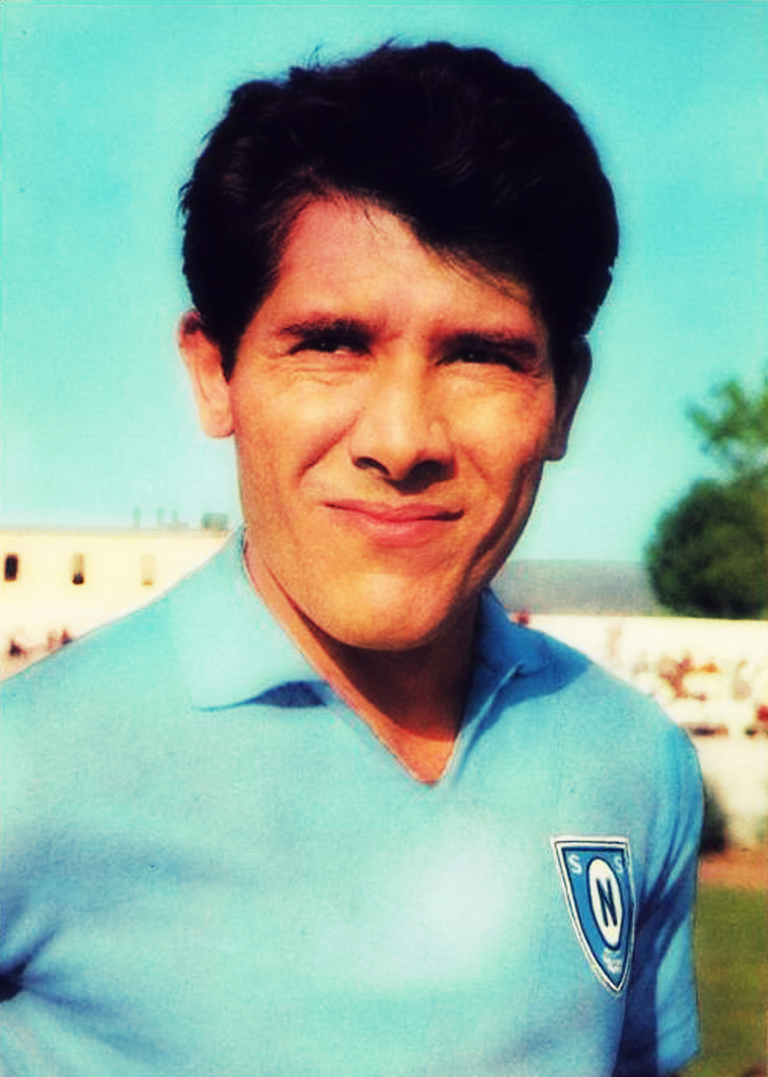

Enrique Omar Sívori was born in 1935 and played for River between 1954 and 1957. He was a crack from a young age. With his skill he brought delights to the three-time champion River 1955/56/57. His talent was evident. And it was no coincidence: after the South American Championship in Lima, he was transferred to Juventus at a record price for world soccer, which took four seasons to be surpassed (with the transfer of Luis Suárez from Barcelona to Inter). With the ten million pesos paid by the Italian club, River managed to finish its stadium, with the construction of the North stand, the one on the Río de la Plata. That is also why, at this time, going to the Sívori has the added value of a tribute.

He dazzled since his arrival to River's youth team. Soon he was already making his debut in the first team. His debut was also a milestone: he replaced one of the most important players in the club's history, Angel Labruna. It was against Lanús and Chiquín -the nickname he carried from his childhood days- scored the fifth goal in a victory to be applauded. Not much was said about him in that April 1954. It was logical: the immense Walter Gómez had scored four goals that afternoon. What followed during his time at Núñez was pure delight, even beyond the statistics: 63 matches, 28 goals and three titles. It was the dribbling at the service of the aesthetics and the team, it was the carefree vocation, it was the audacity as a frequent resource.

"When he was a little boy, he was already an attraction. Everyone came to see how he played the ball. A real phenomenon", Angel Massimo, the enthusiastic president of the Club Teatro Municipal, where the San Nicolás crack played his first charms, once told us. Already as a kid he got angry when he lost the ball; he liked to carry it tied to his boot. And he did it regularly. He was one of the great stars of the 50s and 60s. With hindsight, with Diego having become San Diego of Naples, Guerrin Sportivo magazine referred to Sívori as "The Maradona of the 60s". Alfredo Di Stéfano, another of the timeless cracks, once said about El Cabezón: "He was fantastic; he had everything".

With the dexterity of his pen, journalist Héctor Hugo Cardozo described him, as a tribute, in some chair of this editorial office: "He was far away in time. Maybe very far away, but what does it matter. That time in which pleasant or unpleasant scenes become inviolable treasures for the memory. In which every memory remains forever. And from far away, Enrique Omar Sívori is part of our history: the one that was built episode by episode, with all the fortunes and misfortunes of life itself.

In those early years, when the ball (rag or rubber ball on the ground or cobblestone) was the privileged toy, Sívori was the model to copy. A boy's dream. The crack when cracks abounded. The one who stepped on the ball the best, the one who dribbled the best, the one who slept the yellow number 5 on his left instep, the one who feinted and the rivals fell down like round-footed dummies. That's why every play was transformed into a complete manual of the ideal player. For trickery, for ingenuity, for skill, for talent, for goals. And the figure of the Big Head was magnified in every fantasy told by the newspapers and in every story told by Fioravanti". That fascination was generated by the crack that seemed to skate around the playing field.

FIFA itself, which included Sívori in its list of the 50 best players of the 20th Century, defined him in its Hall of Fame as "The magician of the lower half". His magic and his detail. There was no randomness in his taste for the game. He had a maxim that he respected to the letter and with talent. He explained it himself, when he was still playing: "The only way to entertain the thousands of spectators who come to the court is to entertain yourself. If you don't enjoy yourself, you can't entertain others". And that's what he did. And he also had a particular view on that detail that made him iconic: the low socks. "I invented that, it was something psychological. I thought that by seeing the bare leg, the opponent would hit me a little less..." In any case, he was getting hit a lot. And that used to generate the least attractive of his traits: irascibility. He often got angry and ended up paying for it occasionally with expulsions. It was the imperfect detail that made him more approachable and more lovable.

Above all, Sívori was a true Carusucia. The story he starred in tells the story: there are teams that exceed their own achievements, that exist beyond their greatest accomplishment. The Carasucias of the South American Championship in Lima, in 1957, are a paradigmatic example of this: they played together only 6 official matches, but nobody ever forgot them. In April of that year, Argentina was crowned champion with a 3-0 win over Brazil, with a performance to be kept in the museums of good play. Since then, that forward line of Oreste Corbatta, Humberto Maschio. Antonio Angelillo, Sívori and Osvaldo Cruz have become part of the profuse mythology of Argentine soccer. It was a soccer without mysteries and with glitter. Humberto Maschio said: "Don Stábile didn't ask us for anything strange. He was calm when it came to giving instructions. And if he had something to tell you, he would approach you and talk in your ear. For me, for example, he always asked me to move out of the way. But he gave us freedom to play. For Sívori, that was the ideal context. And something more: it was his springboard to European soccer, after being voted the best player in the competition.

His time at Juventus was pure glory. Eight seasons, three Scudettos, two Italian Cups, Capocannoniere in 1960, Ballon d'Or in 1961. He became an adored player. Since then and forever. Already naturalized, he lent his talent to that Italy that had already adopted him as its own. Then, in Naples, he was a superhero before Maradona. He led the team from the South to fight for the Scudetto for the first time in its history of postponements. For three consecutive seasons, the Light Blue were in the top four.

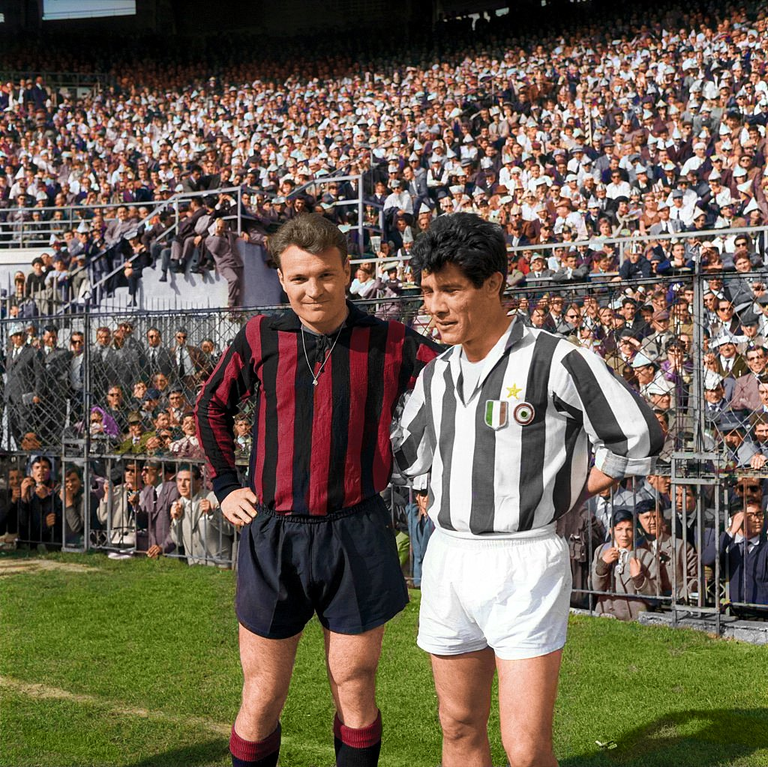

And Sívori earned a standing ovation. There was an affinity between this proletarian Napoli and this footballer who worked miracles with his feet. The significance of his recruitment and then his transfer to Napoli was portrayed four decades later by journalist Enric Gonzalez in his column "Historias del calcio" in El Pais newspaper: "In Turin nobody knew much about that big-headed, rangy guy that the Agnelli family had signed. Juventus of 1957 had just finished a very mediocre season, with a ninth place finish, and the public demanded that Fiat strengthen the team. The Agnelli's car company brought in a star player, John Charles, the giant Welsh striker who arrived from Leeds United.

And that other Argentinian, whose presentation was attended by only a few. Those few did well. El Cabezón came out onto the pitch with shuffling feet and fallen socks, saw the half-empty stands, heard four badly counted applauses and decided to introduce himself: he put the ball on his left foot and ran three full laps around the pitch, running and waving, without the leather touching the ground. The Naples newspapers reported the feat the next day. And from that day on, the Neapolitans dreamed of having for themselves this irreverent and mocking genius who, like Garrincha, would stop to wait for the opponent to make another tunnel or to laugh in his face". It was written somewhere in history: Sívori was an omen of San Diego de Nápoles.

In 2005, when Sívori passed away, Turin and Naples mourned and remembered him. "With Omar Sívori disappears a soccer artist, a great interpreter who transmitted his passion to thousands of tifosi. The image of an atypical footballer will remain in our memories, with his socks always down, his taste for the dribble, his search for spectacle even before the result," said Franco Carraro, then president of the Italian Football Federation. Gianni Rivera, a contemporary of Sivori's and a rival in the Milan jersey, said: "Even for an opponent, it was a pleasure to watch him play.... He thought before everyone else and it was almost impossible to take the ball away from him. He was one of the greats. Giampiero Bonipeti, a teammate of his during his time at the Vecchia Signora, said: "He was a delight: his touch, his dribbling and his extraordinary and damned tunnel that made his opponents go crazy. Sívori was exceptionally classy. Playing with him was a marvel". The Gazzetta dello Sport greeted him with two words: "Addio, genius". The Almirante Brown stand at the Monumental stadium would soon bear his name.

Fue ídolo en River, Juventus y Nápoli. Representó a los seleccionados de Argentina y de Italia. En 1961, ganó el Balón de Oro. Pero sobre todo resultó un óptimo representante del carácter lúdico del fútbol. Su venta al fútbol italiano fue tan importante en su época que con ese dinero River completó la construcción de su estadio, el mítico Monumental.

Está en boca de todos. Es una presencia frecuente en cada diálogo entre hinchas de River. Casi sin darse cuenta él está ahí. "Vamos a la Sívori", dicen camino al Monumental dos hinchas, que pueden ser otros dos cualquiera o miles de otros que por allí andan, cumpliendo con ese rito de ir a ver a River, militando en ese empecinamiento creciente por llenar estadios. También sucede una curiosidad: la mayoría de los que lo mencionan no lo vio jugar. Por una razón sencilla: no habían llegado.

Enrique Omar Sívori nació en 1935 y jugó en River entre 1954 y 1957. Fue crack desde joven. Con su habilidad de potrero aportó delicias al River tricampeón 1955/56/57. Su talento era evidente. Y no hubo casualidad: luego del Sudamericano de Lima, fue transferido a la Juventus en una cifra récord para el fútbol del mundo, que tardó cuatro temporadas en ser superada (con el traspaso de Luis Suárez del Barcelona al Inter). Con los diez millones de pesos que pagó el club italiano, River consiguió terminar su estadio, con la construcción de la tribuna Norte, la del Río de la Plata. También por eso, ir en este tiempo a la Sívori tiene el valor agregado de un homenaje.

Deslumbró desde su llegada a las inferiores de River. Pronto ya estaba debutando en Primera. Su estreno también fue un hito: ingresó en reemplazo de uno de los máximos referentes de la historia del club, Angel Labruna. Fue ante Lanús y Chiquín -el apodo que traía desde los días de la niñez- convirtió el quinto tanto de una goleada para el aplauso. No se habló mucho de él en aquel abril de 1954. Era lógico: el inmenso Walter Gómez había hecho cuatro goles esa tarde. Lo que continuó en su recorrido por Núñez fue puro deleite, incluso más allá de las estadísticas: 63 partidos, 28 goles y tres títulos. Era la gambeta al servicio de la estética y del equipo, era el desenfado por vocación, era la audacia como recurso frecuente.

"De chiquitito ya era una atracción. Todos venían a ver cómo tocaba la pelota. Un verdadero fenómeno", contó en alguna oportunidad Angel Massimo, el entusiasmado presidente del Club Teatro Municipal, en el que el crack de San Nicolás ofreció sus primeros encantos. Ya de pibe se enojaba cuando perdía la pelota; le gustaba llevarla atada a su botín. Y lo conseguía con regularidad. Fue una de las grandes estrellas de los años 50 y 60. Con la perspectiva del tiempo, con Diego convertido en San Diego de Nápoles, la revista Guerrin Sportivo lo mencionó a Sívori como "El Maradona de los 60". Alfredo Di Stéfano, otro de los cracks sin tiempo, dijo sobre El Cabezón alguna vez: "Era fantástico; lo tenía todo".

Con la destreza de su pluma lo describió, a modo de tributo, el periodista Héctor Hugo Cardozo, en alguna silla de esta redacción: "Fue allá lejos en el tiempo. Quizás muy lejos, pero qué importa. Ese tiempo en el que las escenas gratas o ingratas se transforman en tesoros inviolables para la memoria. En el que cada recuerdo queda para siempre. Y desde allá a lo lejos Enrique Omar Sívori forma parte de nuestra historia: la que se fue armando episodio por episodios, con todas las venturas y desventuras de la vida misma.

En ese andar por los años primeros, cuando la pelota (de trapo o de goma sobre la tierra o el empedrado) era el juguete privilegiado, Sívori fue el modelo a copiar. Un sueño de pibe. El crack cuando abundaban los cracks. El que la pisaba mejor, el que gambeteaba mejor, el que dormía la número 5 amarilla en su empeine zurdo, el que amagaba y los rivales se caían como muñecos de pies redondos. Por eso cada jugada se transformaba en un manual completo del jugador ideal. Por picardía, por ingenio, por destreza, por talento, por los goles. Y se agigantaba la figura del Cabezón en cada fantasía que contaban los diarios y en cada relato de Fioravanti". Esa fascinación generaba el crack que parecía patinar por el campo de juego.

La propia FIFA, que ubicó a Sívori en su listado de los 50 mejores jugadores del Siglo XX, lo definió en su Salón de la Fama como "El mago de las medias bajas". Su magia y su detalle. No había azar en su gusto por el juego. Tenía una máxima que respetaba a rajatabla y con talento. Lo explicó él, cuando todavía jugaba: "La única manera de hacer divertir a tantos miles de espectadores que van a la cancha es divertirse uno mismo. Si uno no se divierte, no puede hacer divertir a los demás". Y eso hacía él. Y también tenía una mirada particular sobre ese detalle que lo hizo icónico: las medias bajas. "Eso lo inventé yo, era algo psicológico. Creía que al ver la pierna desnuda, el adversario me pegaría un poco menos..." De todos modos, bastante le pegaban. Y eso solía generar el menos atractivo de sus rasgos: la irascibilidad. Se enojaba con frecuencia y lo terminaba pagando ocasionalmente con expulsiones. Era el detalle imperfecto que lo hacía más cercano y más querible.

Sobre todo, Sívori fue un auténtico Carusucia. Lo cuenta la historia que él protagonizó: hay equipos que exceden sus propias conquistas, que existen más allá de su máximo logro. Los Carasucias del Sudamericano de Lima, en 1957, son un ejemplo paradigmático al respecto: jugaron juntos apenas 6 partidos oficiales, pero nadie los olvidó nunca. En abril de aquel año, Argentina se consagró campeón al golear 3-0 a Brasil, con una actuación para guardar en los museos del buen juego. Desde entonces, aquella delantera de Oreste Corbatta, Humberto Maschio. Antonio Angelillo, Sívori y Osvaldo Cruz ya forma parte de la profusa mitología del fútbol argentino. Era un fútbol sin misterios y con brillos. Lo contó Humberto Maschio: "Don Stábile no nos pedía nada raro. Era tranquilo para dar indicaciones. Y si tenía algo para decirte, se te acercaba y te hablaba al oído. A mí, por ejemplo, me pedía que me desmarcara siempre. Pero nos daba libertades para jugar". Para Sívori aquel fue el contexto ideal. Y algo más: resultó su trampolín al fútbol de Europa, tras ser elegido el mejor jugador de la competición.

Resultó pura gloria su paso por la Juventus. Ocho temporadas, tres Scudettos, dos Copas de Italia, Capocannoniere en 1960, Balón de Oro en 1961. Se convirtió en un futbolista adorado. Desde entonces y para siempre. Ya nacionalizado, prestó su talento a esa Italia que ya lo había adoptado como propio. Luego, en Nápoles, fue superhéroe antes que Maradona. Llevó al equipo del Sur a pelear por el Scudetto por primera vez en su historia de postergaciones. Durante tres temporadas consecutivas, los celestes estuvieron entre los cuatro primeros.

Y Sívori se ganó la ovación perpetua. Había afinidad entre ese Nápoli proletario y ese futbolista hacedor de milagros con los pies. El significado de su contratación y luego de su traspaso al Nápoli, lo retrató cuatro décadas después el periodista Enric González, en su columna "Historias del calcio", del diario El País: "En Turín nadie sabía gran cosa de aquel tipo renegrido y cabezón que habían fichado los Agnelli. El Juventus de 1957 acababa de cerrar una temporada muy mediocre, con un noveno puesto, y el público exigía a la Fiat que reforzara el equipo. La sociedad automovilística de los Agnelli trajo a una estrella, John Charles, el gigantesco ariete galés llegado desde el Leeds United.

Y a ese otro, argentino, a cuya presentación acudieron unos pocos. Esos pocos hicieron bien. El Cabezón salió al césped arrastrando los pies y con las medias caídas, vio las gradas semivacías, escuchó cuatro aplausos mal contados y decidió presentarse: se colocó el balón sobre el pie izquierdo y dio tres vueltas enteras al campo, corriendo y saludando, sin que el cuero tocara el suelo. Los diarios de Nápoles relataron la hazaña al día siguiente. Y desde ese día los napolitanos soñaron con tener para sí a ese genio irreverente y burlón que, como Garrincha, se paraba a esperar al contrario para hacerle otro túnel o para reírsele en la cara". Estaba escrito en algún rincón de la historia: Sívori fue un augurio de San Diego de Nápoles.

En 2005, cuando Sívori falleció, Turín y Nápoles lo lloraron y lo recordaron. "Con Omar Sívori desaparece un artista del fútbol, un gran intérprete que transmitió su pasión a miles de tifosi. Permanecerá en las memorias la imagen de un futbolista atípico, con las medias siempre bajas, su gusto por la gambeta, su búsqueda del espectáculo anteponiéndolo incluso al resultado", expresó Franco Carraro, entonces presidente de la Federación Italiana. Gianni Rivera, contemporáneo de Sívori y rival con la camiseta del Milan, señaló: "Incluso para un adversario, era un placer verlo jugar... Pensaba antes que todos y así resultaba casi imposible quitarle el balón. Fue uno de los grandes". Giampiero Bonipeti, compañero en sus tiempos de la Vecchia Signora, contó: "Era un encanto: el toque del balón, el dribbling y el túnel extraordinario y maldito que hacía enloquecer a sus adversarios. Sívori tenía una clase excepcional. Jugar con él era una maravilla". La Gazzetta dello Sport lo saludó con dos palabras: "Addio, genio". En breve, la tribuna Almirante Brown del estadio Monumental comenzaría a llevar su nombre.

Source images / Fuente imágenes: El Gráfico

Sources consulted (my property) for the preparation of this article. Some paragraphs may be reproduced textually.

Fuentes consultadas (de mi propiedad) para la elaboración del presente artículo. Algunos párrafos pueden estar reproducidos textualmente.

| Argentina Discovery. |  |

|---|---|

| Galería Fotográfica de Argentina. |  |

| Viaggio in Argentina. |  |

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks @ctime!!