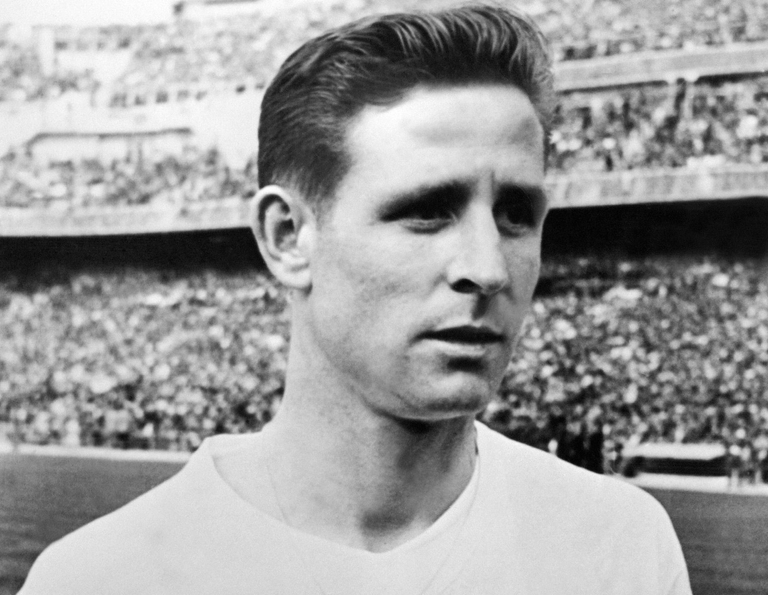

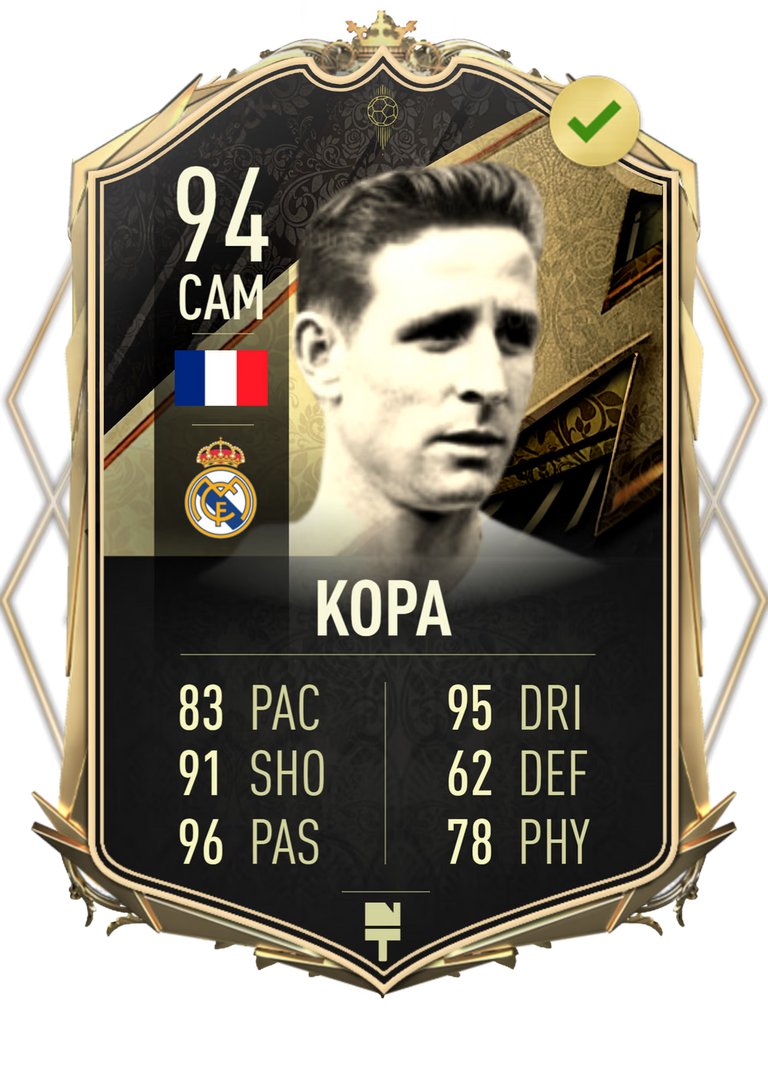

The Frenchman Raymond Kopa was one of the great stars of the 50s. As a teenager, he lost a finger working in a mine. The accident definitely brought him closer to football. He was a figure at Stade de Reims and Real Madrid. In 1958, he won the Ballon d'Or.

Nicolas Sarkozy had not yet completed a year as president of France. He still had the smile with which he had seduced many voters and Carla Bruni. The same smile that he offered at every event that - in those days - allowed him to sustain his popularity.

On that morning in 2008, at the Elysée Palace, the residence of the Head of State, a tribute was taking place: Raymond Kopa - crack of the 50s, crack without time - looked with alien eyes at that celebration in which the center of the scene belonged to him. The country for which he had offered goals, talent, skills, the best dribbles and unforgettable magic was decorating him: for him it was the shine of that Medal of Officer of the Legion of Honor.

The son of Polish immigrants (Kopa is the abbreviation of his birthplace surname, Kopaszewski), that coal mine worker in his teenage days heard praise, bows and anecdotes from his legendary journey. Almost as much as when in 1958 he was recognized as a universal star for his notable participation in the World Cup in Sweden and for that Ballon d'Or that he so deserved and that he won. At the tribute was the then president of the French Football Federation, Jean-Pierre Escalettes. He clapped until his hands broke. He remembered, like many of his age, that youth in which almost everyone wanted to look like that footballer of small size and enormous game.

In each club he was in he provided the same in exchange for the same: delight through ovations. He was the Messi of the 50s, even in the shadow of his beloved teammate Alfredo Di Stéfano. He was on the podium of the best players in Europe for four years, between 1956 and 1959. He once won gold, once silver and twice bronze. In those years he was already playing for the best possible Real Madrid, galactic times with earthly salaries. He won two Spanish Leagues and three Champions Cups (yes, the Champions League now).

But before and after his pioneering excursion to Spain he continued to be a figure of an institution that places him on the pedestal of his mythical life, the Stade de Reims. During his two cycles (the first, after his initial spell at Angers; the second, already in the 60s) he won four French championships. And something else: recognition forever. The White House in Madrid officially places him among the legends of his success story. And he defines it, too: "His short dribbling and his football intelligence were his best virtues. If we add to all this his ability to play in different positions, always offensive, no one is surprised that Kopa gave Madrid an impressive scoring capacity. ".

His contribution to the French team is portrayed by a nickname: after a match against Spain, the English journalist Desmond Hackett, as a result of Kopa's minimal size and maximum influence, baptized him as "The Napoleon of football." And that's what he called himself from then on. In the 1958 World Cup he had the best campaign for the French national team until winning the World Cup that was played forty years later, at home, with Zinedine Zidane as the most visible face. There were ten years dressed in blue (from 1952 to 1962) in which he scored 18 goals in 45 games. In 2011, UEFA presented its highest honorary award - the President's Award - to Kopa. Just Fontaine, his best partner in the national team, added a few words to the occasion: "I want to congratulate Michel Platini for having the initiative to honor one of our most glorious players, because Kopa is undeniably one of them." He was not just any reference; but that of the one who -perhaps- knew him best.

When the football sky embraced Kopa, no one remembered that he had lost a finger working in the mining area of Pas-de-Calais and that that accident ended up bringing him definitively closer to the sport. But at that recent UEFA tribute event, he did remember those days: "I always played in categories older than my age. When I was Under 17, I was already playing in the third division with Noeux-les-Mines. The chief engineer of area three where I worked was also the president of the team, but he did nothing to help me in my football career. Raymond built himself.

On the occasion of the awarding of the last Ballon d'Or, this January, Kopa was interviewed as a presentation of the FIFA Gala. They asked him about a detail that does not go unnoticed: the comparison with Messi. "There are similarities. We measure exactly the same and my strengths were dribbling, speed of execution and precision. It is an honor to be compared to him!" he expressed. And he also referred to Barcelona's constellation of stars: "They say that the Barcelona of today is a bit like the Reims of yesterday. But I can tell you that my Real Madrid was at least as good as this Barça. I only lost one game in three years with Madrid. It is true that we could not have chosen a worse match to lose, because it was against Atlético de Madrid, 1-0. But, joking aside, we were unbeatable in those years. Those who know a lot and saw a lot maintain that he was - due to the particularities of his game - the most similar to the unbeatable Rosario star.

His talent was inexhaustible. And he transcended environments, stages and t-shirts. Also, over time. In August 1973, six years after his retirement, Fontaine - then coach of Paris Saint Germain - invited him to play a game for his team against a regional rival. His performance was an amazement for everyone, even for the protagonist: he dribbled as if to belie his 42 years and scored three goals. That participation opened a door: they offered him a return to football. But not. With the usual prudence he said that he had already offered everything he could offer. At that point, there were not many who compared him to Garrincha. However, everyone then understood that he was still an artist on the pitch. He even able to beat the almanac.

Beyond the playing field, he had other concerns. He had inherited them from the brave times of adolescence, from those days of hands bruised and tanned by hard work. Also from his father and his grandfather, two workers in the mines of northern France. He understood the defense of workers' rights as natural. And he interpreted the footballers of that time as such. In that name he fought. Until the end of the sixties, players belonged to the clubs forever. The club, master and lord; the club's perpetual owner. He didn't like that situation. He didn't think it was fair. And together with Fontaine - Fontaine again - they made a decision that was a milestone and changed the way footballers and institutions interact: he founded the French professional players' union (currently known as the National Union of Professional Footballers, UNFP). ) and promoted the temporary contract among the first decisions. Off the field he also left his mark.

He won medals, the most valuable titles, decorations, cups of all kinds, special distinctions. In 2000, the French newspaper L'Equipe named him one of the three best French footballers of all time (the top 5 was completed by Platini, Zidane, Thierry Henry and Fontaine). In 2004, the highest football entity placed him in its FIFA 100 ranking, which included the 123 best living players. Between those two recognitions there was a piece of news that was spread much less. Kopa - an immense little guy - was selling part of his glory in the name of another quest: collaborating in the fight against cancer. The pain over the death of his son - during the time of Real Madrid - had taught him in one fell swoop that sometimes trophies are just that.

El francés Raymond Kopa fue uno de los grandes cracks de los años 50. En la adolescencia, perdió un dedo trabajando en una mina. El accidente lo acercó defininitivamente al fútbol. Fue figura del Stade de Reims y del Real Madrid. En 1958, ganó el Balón de Oro.

Nicolás Sarkozy aún no había cumplido un año como presidente de Francia. Tenía, todavía, la sonrisa con la que había seducido a muchos votantes y a Carla Bruni. La misma sonrisa que ofrecía en cada evento que -por esos días- le permitían sostener su popularidad.

En aquella mañana de 2008, en el Palacio del Eliseo, la residencia del Jefe de Estado, un homenaje estaba sucediendo: Raymond Kopa -crack de los años 50, crack sin tiempo- miraba con ojos ajenos esa celebración en la que el centro de la escena le pertenecía. El país para el que había ofrecido goles, talento, destrezas, gambetas de las mejores y magias sin olvido lo estaba condecorando: para él era el brillo de esa medalla de Oficial de la Legión de Honor.

El hijo de inmigrantes polacos (Kopa es la abreviatura de su apellido de la cuna, Kopaszewski) , aquel obrero de las minas de carbón en los días de la adolescencia, escuchó elogios, reverencias y anécdotas de su recorrido de leyenda. Casi tanto como cuando en 1958 se recibió de estrella universal por su notable participación en el Mundial de Suecia y por ese Balón de Oro que tanto merecía y que ganó. En el tributo estaba el entonces presidente de la Federación Francesa de Fútbol, Jean-Pierre Escalettes. Aplaudió hasta que se le rompieron las manos. Se acordaba, como muchos de su edad, de aquella juventud en la que casi todos se querían parecer a ese futbolista de tamaño pequeño y juego enorme.

En cada club en el que estuvo brindó lo mismo a cambio de lo mismo: deleite por ovaciones. Fue el Messi de los años 50, incluso a la sombra de su querido compañero Alfredo Di Stéfano. Estuvo durante cuatro años en el podio de los mejores jugadores de Europa, entre 1956 y 1959. Una vez fue oro, una plata y dos bronce. En esos años ya jugaba en el mejor Real Madrid posible, tiempos de galácticos con salarios terrenales. Ganó dos Ligas de España y tres Copas de Campeones (sí, la Champions League de ahora).

Pero antes y después de su pionera excursión a España siguió siendo figura de una institución que lo ubica en el pedestal de su vida mítica, el Stade de Reims. Durante sus dos ciclos (el primero, tras su paso inicial por el Angers; el segundo, ya en los años 60) ganó cuatro campeonatos de Francia. Y algo más: el reconocimiento para siempre. La Casa Blanca de Madrid lo coloca oficialmente entre las leyendas de su historia de éxitos. Y lo define, también: "Su regate en corto y su inteligencia futbolística fueron sus mejores virtudes. Si a todo esto se suma su capacidad para poder jugar en distintas posiciones, siempre ofensivas, a nadie extraña que Kopa otorgara al Madrid una capacidad goleadora impresionante".

A su aporte al seleccionado de Francia lo retrata un apodo: tras un partido frente a España, el periodista inglés Desmond Hackett, a consecuencia del tamaño mínimo y la influencia máxima de Kopa, lo bautizó como "El Napoleón del fútbol". Y así se llamó desde entonces. En el Mundial de 1958 realizó la mejor campaña del seleccionado galo hasta la obtención de la Copa del Mundo que se disputó cuarenta años después, de local, ya con Zinedine Zidane como la cara más visible. Fueron diez años vestido de azul (desde 1952 hasta 1962) en los que brindó 18 tantos en 45 encuentros. En 2011, la UEFA le entregó el mayor galardón honorífico -el Premio del Presidente- a Kopa. Just Fontaine, su mejor socio en el equipo nacional, agregó algunas palabras a la ocasión: "Quiero felicitar a Michel Platini por tener la iniciativa de honrar a uno de nuestros más gloriosos jugadores, porque Kopa es inngablemente uno de ellos". No era una referencia cualquiera; sino la de quien -quizá- mejor lo conocía.

Cuando el cielo del fútbol lo abrazó a Kopa, ya nadie se acordaba de que había perdido un dedo trabajando en la zona minera de Pas-de-Calais y que ese accidente lo terminó acercando definitivamente al deporte. Pero en ese evento reciente del homenaje de la UEFA, él sí recordó aquellos días: "Siempre jugaba en categorías superiores a mi edad. Cuando era Sub 17, ya estaba jugando en tercera división con el Noeux-les-Mines. El ingeniero jefe del área tres en la que yo trabajaba también era el presidente del equipo, pero no hizo nada para ayudarme en mi carrera de futbolista". Raymond se construyó a sí mismo.

En ocasión de la entrega del último Balón de Oro, en este enero, Kopa fue entrevistado a modo de presentación de la Gala de la FIFA. Le preguntaron por un detalle que no pasa inadvertido: la comparación con Messi. "Hay semejanzas. Medimos exactamente lo mismo y mis puntos fuertes eran el regate, la rapidez en la ejecución y la precisión. ¡Es un honor que me comparen con él!", expresó. Y también se refirió a la constelación de estrellas del Barcelona: "Dicen que el Barcelona de hoy es un poco como el Reims de ayer. Pero le puedo decir que mi Real Madrid era al menos tan bueno como este Barça. Yo sólo perdí un partido en tres años con el Madrid. Es verdad que no pudimos elegir otro encuentro peor para perder, porque fue contra el Atlético de Madrid, por 1-0. Pero, bromas aparte, éramos imbatibles en aquellos años". Quienes mucho conocen y mucho vieron sostienen que era -por las particularidades de su juego- el más parecido al inmejorable crack rosarino.

Su talento era inagotable. Y trascendía ambientes, escenarios y camisetas. También, al paso del tiempo. En agosto de 1973, seis años después de su retiro, Fontaine -entonces entrenador del Paris Saint Germain- lo invitó a jugar un partido para su equipo frente a un rival regional. Su actuación fue un asombro para todos, incluso para el protagonista: gambeteó como para desmentir sus 42 años e hizo tres goles. Esa participación abrió una puerta: le ofrecieron volver al fútbol. Pero no. Con la prudencia de siempre dijo que ya había ofrecido todo lo que podía ofrecer. A esa altura, no quedaban muchos que lo compararan con Garrincha. Sin embargo, todos comprendieron entonces que seguía siendo un artista sobre el césped. Incluso capaz de vencer al almanaque.

Más allá del terreno de juego, tenía otras inquietudes. Las había heredado de los tiempos bravos de la adolescencia, de aquellos días de manos lastimadas y curtidas por el trabajo arduo. También de su padre y de su abuelo, dos laburantes de las minas del norte francés. Entendía como natural la defensa de los derechos de los trabajadores. E interpretaba a los futbolistas de ese tiempo como tales. En nombre de eso militó. Hasta finales de los años sesenta los jugadores pertencían a los clubes para siempre. El club amo y señor; el club dueño perpetuo. No le gustaba esa situación. No le parecía justa. Y junto a Fontaine -otra vez Fontaine- tomaron una decisión que fue un hito y modificó el modo de vincularse entre los futbolistas y las instituciones: fundó el sindicato de jugadores profesionales francés (en la actualidad conocido como la Unión Nacional de Futbolistas Profesionales, UNFP) e impulsó el contrato temporal entre las primeras decisiones. Afuera del campo también dejó su huella.

Ganó medallas, los títulos más valiosos, condecoraciones, copas de todo tipo, distinciones especiales. En el año 2000, el diario francés L'Equipe lo señaló como uno de los tres mejores futbolistas franceses de todos los tiempos (el top 5 lo completaban Platini, Zidane, Thierry Henry y Fontaine). En 2004 la máxima entidad del fútbol lo ubicó en su ranking FIFA 100, que incluía a los 123 mejores jugadores vivos. Entre esos dos reconocimientos hubo una noticia que se difundió mucho menos. Kopa -pequeño inmenso- estaba vendiendo parte de sus vitrinas de gloria en nombre de otra búsqueda: colaborar en la lucha contra el cáncer. El dolor por la muerte de su hijo -en tiempos del Real Madrid- le había enseñado de un solo golpe que a veces los trofeos son apenas eso.

Source images / Fuente imágenes: UEFA.

Sources consulted (my property) for the preparation of this article. Some paragraphs may be reproduced textually.

Fuentes consultadas (de mi propiedad) para la elaboración del presente artículo. Algunos párrafos pueden estar reproducidos textualmente.

| Argentina Discovery. |  |

|---|---|

| Galería Fotográfica de Argentina. |  |

| Viaggio in Argentina. |  |

Telegram and Whatsapp

Thank you for curating and supporting my content @blurtconnect-ng.

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks!