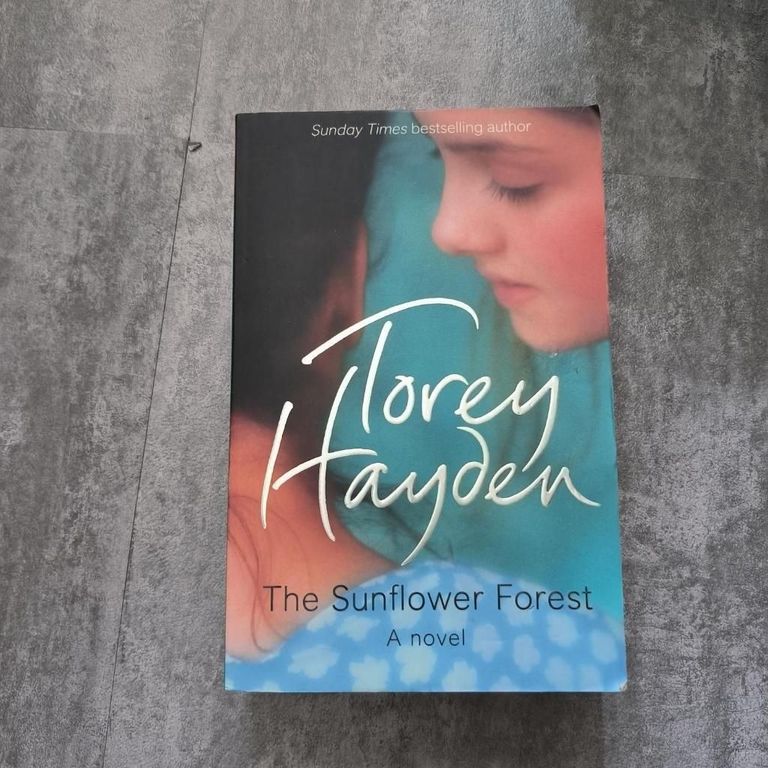

Here is a treasure: a novel for adults that speaks in the authentic voice of a 17-year-old girl, delving deeply into her psyche.

Lesley's Hungarian mother, Mara, - charming, candid, kind - was traumatized by her teenage experiences during the Nazi era. Although her American husband and daughters try to live a normal life in Kansas, Mara subjects them to her whims and quirks. Lesley tries to understand her, but caring for Mara is extremely painful, which sets her apart from her peers.

When Mara's psychosis turns tragic, Lesley travels to Wales to search for what her mother always remembered with great joy, a forest of sunflowers.

Aquí hay un tesoro: una novela para adultos que habla en la voz auténtica de una jóven de 17 años, sumergiendo mucho en su psiquis.

La madre húngara de Lesley, Mara, - encantadora, cándida, amable - fue traumatizada por sus experiencias de adolescente en el tiempo de los Nazis. Aunque su marido americano y sus hijas tratan de vivir una vida normal en Kansas, Mara los somete a sus caprichos y sus peculiaridades. Lesley trata de entenderla, pero ocuparse de Mara está sumamente penoso, lo que la destaca de sus compañeras.

Cuando la psicosis de Mara resulta una tragedia, Lesley viaja a Gales para buscar de lo que siempre se acordaba su madre con gran alegría, un bosque de girasoles.

Leslie and Megan are the owners of 17- and 9-year-old Sorelle. I live in late 20th century America, in an apparently normal family, with the father who works and the mother who thinks about the children and the house. This is what the other person perceives. Leslie and Megan were lucky, they had the parents who loved him and who loved Vicenda.

Reality is here to last, Mara, the mother, many times a day with the demons of the past, fateful to live in the present and close to the solutions to the errors that she had to commit when she was just a teenager. The rest of the family doesn't pay for anything, everyone has to spend time living with Mara's strangers: that at the beginning they planted "eccentricity", and they tended to be pericolose. The book is written very well, the narrative style is optimal.

Ciò nonostante, the first part of the book is a bit mature. Ho trovato invece reuscitissime le last 100 pagine, when the scene changes and the author ci racconta il Galles: sono pagine beautiful, le descrizioni del paesaggio sono perfette, leggendo sembra quasi di felt and profumi di este terra selvaggia. 10 and what I did in the last part of this book, but I don't feel like giving it this vote on the first page, write very well and forse a little bit.

Leslie y Megan son dos hermanas de 17 y 9 años. Viven en los Estados Unidos de finales del siglo XX, en una familia aparentemente normal, con un padre trabajador y una madre que cuida de los niños y de la casa. Esto es lo que percibe la otra persona. Leslie y Megan tienen suerte, tienen dos padres que las aman y se aman entre sí.

Lamentablemente, la realidad es más dura. Mara, la madre, lucha a diario con los demonios del pasado, lucha por vivir el presente e intenta enmendar los errores que se vio obligada a cometer cuando era apenas una adolescente. El resto de la familia paga las consecuencias, todos se ven obligados a vivir con las rarezas de Mara: lo que al principio parecen "excentricidades", luego se convierten en tendencias peligrosas. El libro está muy bien escrito, el estilo narrativo es excelente.

Sin embargo, la primera parte del libro es un poco larga. Me parecieron muy logradas las últimas 100 páginas, cuando cambia el escenario y el autor nos habla de Gales: son páginas preciosas, las descripciones del paisaje son perfectas, mientras lo lees casi parece que puedes oler los aromas de este tierra salvaje Un 10 sobre 10 por tanto para la última parte de este libro, pero no me apetece dar la misma puntuación a las doscientas primeras páginas, que están muy bien escritas pero quizás un poco aburridas.

That year my biggest desire was to date a boy.

At seventeen, I hadn't been on a date yet. I had everything else: breasts, armpit hair, periods, desire.

I definitely had the desire.

Once, when I was little and didn't quite know how it worked, my best friend and I pretended to make love, legs spread like scissors, until we were genitals to genitals, with each other's slippers under the other's nose. My grandmother caught us like that. He sent Cecily home and spanked me with the handle of a wooden spoon, then made me sit in the pantry and say Hail Marys. I had no doubt, he said. I inherited that kind of interest from my mother. Maybe it was true.

Still, even though I was little, I decided it wasn't so bad to have that kind of interest.

By the time I was seventeen, however, I had received only a Valentine's card from Wayne Carmelee and three stolen kisses under the bleachers at the Sandpoint County Fair in Idaho from a scoutmaster.

It was a source of great personal dismay for me, and I was certainly not helped by my nine-year-old sister Megan, who never missed an opportunity to confirm to me that I really was as awful as I felt. She even hinted that I smelled bad and the boys could smell it.

My father told me that I simply had to be patient. It was natural and you can't stop nature from taking its course.

My time would come, too, he assured me. I replied that if we hadn't been constantly moving from place to place, perhaps nature would have managed to track me down by now.

I ended up asking my mother for comfort. I asked her when she first fell in love.

"Hans Klaus Fischer," she replied. I found her in the kitchen, busy scrubbing the floor. Kneeling on the linoleum, her hair tied back with a red bandana, she paused and considered my question. And he chuckled. He went to the kitchen counter to get the cigarettes, then sat back down on the floor and leaned his back against the cupboard near the sink. He crossed his legs and rested the ashtray on one knee. “I lived in Dresden with Aunt Elfie. You know, I wasn’t allowed to see the boys.

I was only fifteen and my aunt told me I couldn’t go out yet.

Well, they were very strict in those days.” She lit the cigarette, and her eyes were smiling. We both knew that what Aunt Elfie said probably never had much influence on what my mother did.

“He was the baker's son. I met him because Aunt Elfie sent me to buy bread every day. If she had sent Birgitta, who knows? Maybe I would never have met him. But Birgitta was lazy. Anyway, every day I went to the back room to bring down the loaves.”

She paused, but continued to look at me. “Would you like to know if he was beautiful?” “Was it nice, Mom?” I asked. You always had to encourage your mother to tell you her stories. It was as funny as the story itself.

“Was he beautiful? Well, listen. His hair was about the same color as yours. A little darker, perhaps, but styled like yours. That was how it was done with boys back then.

He had blue eyes, or rather blue-green. And Bright. A bright blue-green, very intense.

The same color as certain antique vases. And his lips were beautiful.

Thin. I don't normally like thin lips on a man, but on Hans Klaus Fischer they gave an expression that was... well, very important. Proud is the right word. He was standing in the back room removing loaves of bread, and I was thinking: Mara, he has to be your boyfriend. You just had to look at him to understand how important he was."

He looked at me and chuckled. "I was very much in love with him.

Every day I went to get the bread and while I waited I could think of nothing else but kissing those beautiful, important-looking lips.

"And you kissed him?" "Well, at first it was very difficult for him to notice me. “I was just one of the many girls in love with Hans Klaus Fischer.”

"But then you managed to make him fall in love with you, didn't you?" She continued to laugh quietly. With one hand she arranged the long, thin strands of hair that escaped from her scarf and said nothing. Mom didn't need it. All she had to do was smile.

"What did you do? How did you get him to notice you despite all those girls? "I started wearing my Bund Deutscher Mädchen uniform to go buy bread. Every day.

Even when there was no meeting. “You know, he was a group leader of the Youth Movement.” She paused to think, staring at the tip of her cigarette.

The smile returned to her lips.

“Sometimes I saw him in the back room and he was wearing his uniform.

He looked handsome in that uniform. When he was wearing it, there was something solemn about his way of walking: maybe he felt like someone in that uniform. And

Then I thought: Mara, he will like you if he thinks you are a convinced follower of the BdM.”

“And he? " She looked at me with a wink.

"But what did Aunt Elfie say? Didn't she scold you because you weren't allowed to go out with the boys?" "Well, a little, yes. At first. But I told her that Hans Klaus came from a very good family. I told her he was a good boy.

He did very well at school, you know, and I once heard his father tell Mrs. Schwartz at the bakery that Hans Klaus would probably be chosen by the Adolf Hitler School. It was almost a certainty, she said. When my aunt found out, she said I could go dancing with him on Friday nights. As long as Birgitta came too, you understand? Raise. "To make sure I never found out too much about kissing those beautiful lips. They were very strict in those days.

Not like now."

"But how did you get him to fall in love with you? How did you get him to ask you out in the first place? Still holding the cigarette in her hand, Mom looked at it and finally stubbed it out in the ashtray. The floor was still damp all around and we were sitting close together, entrenched behind the brooms, bucket and tea towels, leaning with our backs against the kitchen cupboard.

“I behaved a bit badly,” Mom said conspiratorially.

“What did you do?” “Well, one time, when he came into the shop to talk to me, I told him I was the Archduke’s niece.”

I laughed. “Really?” “I told him my grandfather was the Archduke and that I had been sent to Dresden for my safety. I lived with Aunt Elfie, who was not my real aunt but a housekeeper my family paid to look after me.”

I was impressed and found it amusing, as was Mom: he must have displayed such melodramatic realism that poor Hans Klaus Fischer didn’t even understand what was happening to him.

“But how did you come up with that?” I asked.

He laughed and shrugged. “I don’t know. I just did.

I wanted to make sure he liked me. I was afraid he wouldn’t.”

“But it was a lie, Mom,” I insisted, still amused as I imagined the scene.

She shrugged again and pursed her lips in a thoughtful expression.

“No. Not exactly. It was just a story. I didn’t mean any harm. I just did it because I didn’t have any interesting enough truth to tell him.”

“So you told him the Archduke was your grandfather?” “Well, you know, you have to understand, I was desperate for him. I did it for the greater good. I thought if he believed me, he would definitely want to take me dancing. And once he met me, it wouldn’t matter who he was related to.” He glanced at me sideways, a playful light shining in his eyes.

“You have to understand, I was only fifteen. We're all a little crazy at fifteen, believe me."

"Did he ever find out the truth?" She shrugged and got down on her knees to finish mopping the floor. "I don't know. Then I went to Jena, and I never saw him again."

I was dreaming. The house on Stuart Avenue where we lived before Megan was born.

I walked up the stairs and found myself in the small attic my father had converted into a bedroom for me. I was standing in front of the small window and looking out at the street.

Ese año mi mayor deseo era salir con un chico.

A los diecisiete años, aún no había tenido ninguna cita. Tenía todo lo demás: pechos, vello en las axilas, períodos, deseo.

Definitivamente tenía el deseo.

Una vez, cuando era pequeña y no sabía muy bien cómo funcionaba, mi mejor amiga y yo fingimos hacer el amor, con las piernas abiertas como tijeras, hasta que nos encontramos genitales contra genitales, con las zapatillas de cada una bajo la nariz de la otra. Mi abuela nos sorprendió así. Él envió a Cecily a casa y me dio una palmada con el mango de una cuchara de madera, luego me hizo sentarme en la despensa y rezar Avemarías. No tenía ninguna duda, dijo. Heredé ese tipo de interés de mi madre. Quizás era cierto.

Aún así, aunque era pequeño, decidí que no era tan malo tener ese tipo de interés.

Sin embargo, cuando cumplí diecisiete años, solo había recibido una tarjeta de San Valentín de Wayne Carmelee y tres besos robados bajo las gradas de la Feria del Condado de Sandpoint en Idaho de un jefe scout.

Fue una fuente de gran consternación personal para mí, y ciertamente no me ayudó mi hermana Megan, de nueve años, que nunca perdió una oportunidad de confirmarme que realmente era tan horrible como me sentía. Incluso insinuó que yo olía mal y los chicos podían olerlo.

Mi padre me dijo que simplemente tenía que tener paciencia. Fue algo natural y no se puede impedir que la naturaleza siga su curso.

Mi momento también llegaría, me aseguró. Le respondí que si no hubiésemos estado moviéndonos constantemente de un lugar a otro, quizá la naturaleza ya habría logrado localizarme.

Terminé pidiéndole consuelo a mi madre. Le pregunté cuándo se enamoró por primera vez.

—Hans Klaus Fischer —respondió. La encontré en la cocina, ocupada fregando el suelo. De rodillas sobre el linóleo, con el cabello atado con un pañuelo rojo, se detuvo y consideró mi pregunta. Y él se rió entre dientes. Fue al mostrador de la cocina para buscar los cigarrillos, luego se sentó nuevamente en el suelo y apoyó la espalda contra el armario cerca del fregadero. Cruzó las piernas y apoyó el cenicero sobre una rodilla. «Viví en Dresde con la tía Elfie. ¿Sabes? No me permitieron ver a los chicos.

Sólo tenía quince años y mi tía me dijo que todavía no podía salir.

Bueno, eran muy estrictos en aquellos días". Encendió el cigarrillo y, encima, sus ojos sonreían. Ambos sabíamos que lo que decía la tía Elfie probablemente nunca tuvo mucha influencia en lo que hacía mi madre.

«Era el hijo del panadero. Lo conocí porque la tía Elfie me mandaba a comprar pan todos los días. Si hubiera enviado a Birgitta, ¿quién sabe? Quizás nunca lo hubiera conocido. Pero Birgitta era perezosa. De todos modos, todos los días iba a la trastienda a bajar los panes”.

Hizo una pausa, pero continuó mirándome. -¿Te gustaría saber si fue hermoso? "¿Estuvo bien, mamá?" Yo pregunté. Siempre tuviste que animar a tu madre a que te contara sus historias. Fue tan divertido como la historia misma.

«¿Fue hermoso? Bueno, escucha. Su cabello era aproximadamente del mismo color que el tuyo. Un poco más oscuro, quizás, pero con estilo como el tuyo. Así se hacía entonces con los varones.

Tenía los ojos azules, o más bien verde azulados. Y brillante. Un azul verdoso brillante, muy intenso.

El mismo color que ciertos vasos antiguos. Y sus labios eran hermosos.

Delgado. Normalmente no me gustan los labios finos en un hombre, pero en Hans Klaus Fischer dieron una expresión que era... bueno, muy importante. Orgulloso es la palabra correcta. Él estaba parado en la trastienda retirando hogazas de pan, y yo estaba pensando: Mara, él tiene que ser tu novio. Sólo había que mirarlo para entender lo importante que era".

Él me miró y se rió entre dientes. «Estaba muy enamorada de él.

Todos los días iba a buscar el pan y, mientras esperaba, no podía pensar en otra cosa que en besar aquellos labios tan bonitos y de aspecto importante.

-¿Y lo besaste? «Bueno, al principio le resultó muy difícil fijarse en mí. “Yo era sólo una de las muchas chicas enamoradas de Hans Klaus Fischer”.

—Pero luego lograste que se enamorara de ti, ¿verdad? Ella seguía riendo en voz baja. Con una mano acomodó los largos y finos mechones de cabello que se le escapaban del pañuelo y no dijo nada. Mamá no lo necesitaba. Todo lo que tenía que hacer era sonreír.

"¿Qué hiciste? ¿Cómo lograste que él se fijara en ti a pesar de todas esas chicas? «Empecé a usar mi uniforme de la Bund Deutscher Mädchen para ir a comprar pan. Cada día.

Incluso cuando no había reunión. “Ya sabes, él era un líder de grupo del Movimiento Juvenil”. Se detuvo a pensar, mirando fijamente la punta de su cigarrillo.

La sonrisa volvió a sus labios.

«A veces lo veía en la trastienda y llevaba su uniforme.

Se veía guapo con ese uniforme. Cuando lo llevaba, su manera de caminar tenía algo de solemne: tal vez se sentía alguien con ese uniforme.

Entonces pensé: Mara, le gustarás si piensa que eres una seguidora convencida del BdM».

"¿Y él?" Me miró con un guiño.

«¿Pero qué dijo la tía Elfie? ¿No te reprendió porque no te permitían salir con los chicos? «Bueno, un poco, sí. Al principio. Pero le dije que Hans Klaus venía de una muy buena familia. Le dije que era un buen chico.

Le fue muy bien en la escuela, ¿sabe?, y una vez oí a su padre decirle a la señora Schwartz en la panadería que Hans Klaus probablemente sería elegido por la Escuela Adolf Hitler. Era casi seguro, dijo. Cuando mi tía se enteró, dijo que podía ir a bailar con él los viernes por la noche. Mientras Birgitta viniera también, ¿entiendes? Elevar. «Para asegurarme de que nunca descubriría mucho sobre besar esos hermosos labios. Eran muy estrictos en aquellos días.

No como ahora."

«Pero ¿cómo lograste que se enamorara de ti? ¿Cómo lograste que él te invitara a salir en primer lugar? Todavía sosteniendo el cigarrillo en la mano, mamá lo miró y finalmente lo apagó en el cenicero. El suelo estaba todavía húmedo por todos lados y estábamos sentados muy juntos, atrincherados detrás de las escobas, el cubo y los paños de cocina, apoyados con la espalda contra el armario de la cocina.

—Me porté un poco mal —dijo mamá en tono conspirador.

"¿Qué hiciste?" —Bueno, una vez, cuando entró en la tienda a hablar conmigo, le dije que era la sobrina del Archiduque.

Me reí. "¿En serio?" «Le dije que mi abuelo era el Archiduque y que me habían enviado a Dresde para mi seguridad. Vivía con la tía Elfie, que no era mi verdadera tía sino una ama de casa a la que mi familia pagaba para que me cuidara”.

Me impresionó y me pareció divertido, igual que mamá: debió mostrar un realismo tan melodramático que el pobre Hans Klaus Fischer ni siquiera entendió lo que le estaba pasando.

—Pero ¿cómo se te ocurrió? Yo pregunté.

Él se rió y se encogió de hombros. "No lo sé. Acabo de hacerlo.

Quería asegurarme de que le agradaba. Tenía miedo de que no fuera así."

—Pero era mentira, mamá —insistí, todavía divertida mientras imaginaba la escena.

Ella se encogió de hombros nuevamente y frunció los labios en una expresión pensativa.

"No. No exactamente. Fue solo una historia. No quise hacer daño. Sólo lo hice porque no tenía ninguna verdad lo suficientemente interesante para contarle”.

—Entonces ¿le dijiste que el Archiduque era tu abuelo? —Bueno, ya sabes, tienes que entenderlo, estaba desesperada con él. Lo hice por el bien mayor. Pensé que si me creía, definitivamente querría llevarme a bailar. Y una vez que me conociera, no importaría con quién estuviera emparentado". Él me miró de reojo, con una luz juguetona brillando en sus ojos.

“Tienes que entenderlo, sólo tenía quince años. Todos estamos un poco locos a los quince, créeme."

"¿Alguna vez descubrió la verdad?" Se encogió de hombros y se puso de rodillas para terminar de fregar el suelo. "No sé. Después fui a Jena, y nunca lo volví a ver."

Estaba soñando. La casa en Stuart Avenue donde vivíamos antes de que naciera Megan.

Subí las escaleras y me encontré en el pequeño ático que mi padre había convertido en dormitorio para mí. Me encontraba de pie frente a la pequeña ventana y miraba hacia la calle.

Source image / Fuente imagen: Torey Hayden.