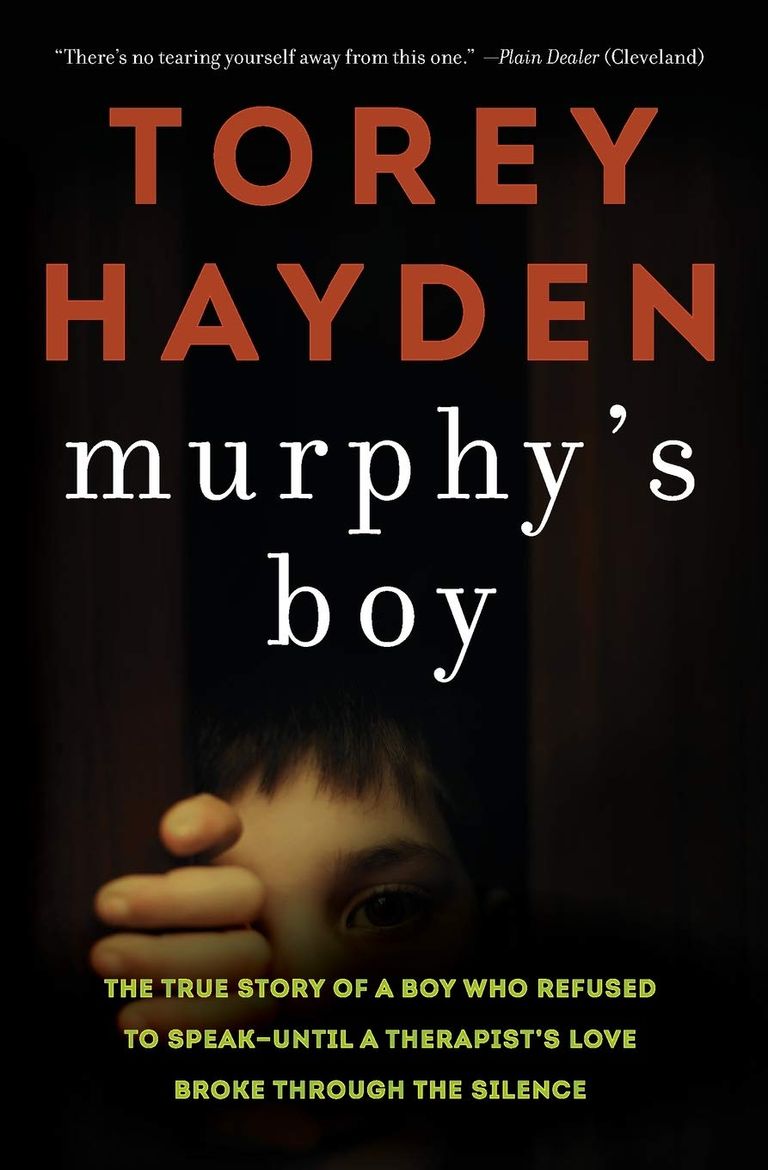

Murphy's Boy by Torey Hayden is the heartbreaking true story of a teenager who cannot overcome the traumas of his childhood.

His name was Kevin, but his keepers called him ‘Zoo Boy’. He didn't talk. He hid under tables and surrounded himself with bars of chairs. He hadn't left the house in all the four years since he arrived. He was afraid of water and never showered. He was afraid to be naked, afraid to change his clothes. He was almost 16 years old.

Feeling very desperate about the situation, the team at the Adolescent Treatment Centre where Kevin was living employed Torey Hayden. When Torey read to him and encouraged him to read aloud, crawling under the table and into his grids of chairs, Kevin began to talk. Then he even drew and painted and thus demonstrated a sharp thought and a burning, murderous hatred of his stepfather.

Hayden writes very legibly. Despite having been very alarming, scaring everyone, Kevin did not scare Torey, and the book is not scary either. Giving everyone confidence is what we need. In our messed up world, love still opens ways. We can heal if we just listen.

Like all Hayden's books, this one too is, unfortunately, a true story which, as such, touches our hearts and moves us, making us feel close to the protagonist and letting him into our lives, while at the same time making us suffer with him, because it hurts inside to discover little by little what traumas an ordinary boy (who could be a neighbour, our son's playmate, our childhood friend) has lived through and lives through every day, forced by his fears to hide and isolate himself from the world.

Kevin, abandoned by his mother who prefers to give him up rather than her abusive husband, reveals himself as an adolescent who only needs the affection and trust of adults, but above all it is he who needs to regain trust in others, a very difficult path given his past, but which in the end ends positively, thus leaving a breath of hope for everyone.

Se llamó Kevin, pero sus cuidadores le llamaron “Zoo Boy”. No habló. Se escondió debajo de mesas y se rodeó de rejas de sillas. No había salido de la casa en todos los cuatro años desde que él llegó. Tenía miedo al agua y no se duchaba nunca. Tenía miedo de estar desnudo, tenía miedo de cambiarse su ropa. Tenía casi 16 años.

Sintiéndose muy desesperados por esa situación, el equipo del Centro de Tratamiento para Adolescentes en que vivía Kevin empleó a Torey Hayden. Cuando Torey le leyó y le animó a leer en voz alta, gateando por debajo de la mesa y dentro de su rejas de sillas, Kevin empezó a hablar. Luego incluso dibujó y pintó y así demostró un pensamiento agudo y un odio ardiendo y asesino contra su padrastro.

Hayden escribe de manera muy legible. A pesar de haber estado muy alarmando, dando miedo a todos, Kevin no le dió miedo a Torey, y el libro no da miedo tampoco. Dando confianza a todos es lo que nos hace falta. En nuestro mundo tan estropeado el amor todavía abre caminos. Podemos curarnos si sólo escuchamos.

Como todos los libros de Hayden, también éste es, desgraciadamente, una historia real que, como tal, nos llega al corazón y nos conmueve, haciéndonos sentir cerca del protagonista y dejándolo entrar en nuestras vidas, al tiempo que nos hace sufrir con él, porque duele por dentro descubrir poco a poco qué traumas ha vivido y vive cada día un chico corriente (que podría ser un vecino, el compañero de juegos de nuestro hijo, nuestro amigo de la infancia), obligado por sus miedos a esconderse y aislarse del mundo.

Kevin, abandonado por su madre que prefiere renunciar a él antes que a su marido maltratador, se revela como un adolescente que sólo necesita el afecto y la confianza de los adultos, pero sobre todo es él quien necesita recuperar la confianza en los demás, un camino muy difícil dado su pasado, pero que al final termina de forma positiva, dejando así un soplo de esperanza para todos.

Zoo-boy.

The legs of the table were the bars of his cage. He swung his arms above his head, as if to protect himself. Back and forth, back and forth. An assistant urged him to get out from under the table, but in vain.

He swayed, back and forth, back and forth.

I watched him from behind the mirror-window.

<How old is he?> I asked the woman on my right.

<Fifteen.

That's all you could say to a child. I leaned against the glass, to get a better look at him. <How long has he been here?> I asked.

<Four years.

<Without ever speaking?>

Never speaking The woman raised her eyes to look at me, in the gloomy darkness of that room behind the mirror.

<Without ever letting me hear the sound of her voice.

I stared at her for a while longer. Then I picked up the box with my paraphernalia and entered the room on the other side of the mirror. The attendant turned away from him as I entered, and was glad to leave. I heard the outer door close in the hallway and realised that he had gone to stand behind the mirror to watch us. In the room it was just Zoo-boy and me.

Cautiously, I set the box on the floor. I waited for a moment, to see if he would react to the presence of a new person in the room; but he didn't react. So I approached. I sat down on the floor, an arm's length away from where he was barricaded under the table. He was still rocking, bent over, arms around his knees. I couldn't get an idea of his height.

Kevin?

He didn't react.

Unsure of what to do, I looked around me. I sensed the presence of an audience behind the mirror. They were talking, in there, indistinct voices, a faint, undulating murmur, like the wind in the reeds on a summer afternoon. But I knew what the sound was.

The boy did not show his fifteen years. Though, huddled as he was, I couldn't see him properly, he didn't look so grown up. I would have given him nine years, maybe. Or eleven. Not nearly sixteen.

Kevin, I repeated, <my name is Torey. Remember Miss Wendolowski told you that one person was going to work with you? That person is me. I'm Torey, and I work with people who have trouble talking.

Still rocking: you'd have thought she didn't even notice me. There was a heavy silence around us, barely stirred by the rhythmic sound of his body against the linoleum of the floor.

I began to talk to him, in a soft, caressing voice, like the one you would use with a frightened puppy. I told him why I had come, the things I would do with him, the children I had happily worked with. I told him about me. What I said didn't matter, only the tone.

There was no reaction. He swayed, nothing more.

Minutes passed. I started to not know what to say anymore. It wasn't easy to have a one-sided conversation like that, but what made it even harder was not so much Zoo-boy as the presence of those ghosts on the other side of the mirror. It was easy to feel stupid talking to yourself when there were half a dozen invisible people watching. I finally pulled out my paraphernalia box and picked up a paperback book, a detective story about a boy and his friend. Now I'll read you a story, I said to Zoo-boy, so we'll feel a bit more comfortable.

<Chapter one. The long road.

I read.

And I read again.

On the clock face the minute hand was turning.

Every now and then there was the muffled sound of a door opening and closing, beyond the mirror. They were leaving, one by one. There was nothing going on in there worth wasting the afternoon for.

I didn't read much. The story wasn't compelling.

And Zoo-boy was just rocking.

I kept reading. And counting how many times the door opened and closed. How many people had entered the room behind the mirror? I couldn't remember exactly.

Six? Seven? And how many had already left? Five?

I read on.

Click-click. Another one had left.

Click-click. And that made seven.

I read on. My voice had become the only sound in the room. I looked up. Zoo-boy had stopped rocking. Slowly, he lowered his arms to get a better look at me. He smiled. He was no fool. He had counted too.

He nodded to me, a small movement within the confines of the table and chairs.

<What?> I asked, not understanding what he was trying to communicate.

He nodded again, this time more broadly. But it was not a simple gesture. It was a sentence, rather, so to speak, a period of gestures.

I still didn't understand. I moved a chair to get a better look, but I had to ask him to repeat himself.

There was something he wanted me to know. His were poetic gestures, in their swirls and compelling spirals. A dance of the hands. But they were not the signs of a language I knew, the signs used by the deaf and dumb or the alphabet of the hands. I didn't understand it.

From under the table came a deep sigh. He grimaced at me. Then, patiently, he repeated his gestures again, this time with greater slowness and emphasis, as when addressing a slightly mute child. And the fact that he could not make himself understood discouraged him.

In the end he gave up. We sat in silence, staring at each other.

I still had the book in my hand, so in a desperate attempt to fill the void, I asked him if he wanted me to read on. He nodded.

I leaned against the wall. <Chapter five. Out of the cave.

Zoo-boy struggled to move the other chair from the table and leaned forward to touch my jeans. I looked up.

His mouth was open and he was pulling his lower jaw down with one hand. He pointed to his throat. Then, dejected, he shook his head.

I had been working in that clinic as a research psychologist for a little over a year. I had spent most of my professional life teaching. I had held every possible role in the field, from teaching in regular primary schools to teaching in universities, from teaching in innovative schools with flexible working hours to teaching in closed classes in the paediatric ward of a state mental institution. I loved teaching.

I had always loved it, and I still do. But over the years, general pedagogical concepts, especially in the field of special education, had started to change, and now I felt like an outsider in that world.

So I decided to do a doctorate in special education. I don't know exactly why. The degree itself didn't interest me very much; it was too high a qualification to go back to teaching in a school. And there were no other aspects in the field of education that interested me.

I certainly never wanted to be in administrative positions. So I went ahead and studied. Ultimately, I think it was a way of doing something while I was deciding what direction to take in my life later on.

Deep in my heart I hoped that the pendulum of pedagogy would swing back and that I could return to teaching without compromising my convictions.

But during those four years of study, the change did not happen, and I was brutally faced with the choice of either getting my diploma and closing the school door behind me forever, or leaving everything halfway and trying something else. In the end I opted for the latter, because I couldn't bear the thought of never going back to teaching. So I left Minneapolis and the university with nothing to show for my four years of study.

During all that time I had been researching a little known psychological phenomenon, elective mutism. It is an emotional disorder that occurs mainly in children. The child is physically able to speak, but for psychological reasons refuses to do so. Many of these children actually speak to someone, usually family members at home, but become deliberately mute to everyone else. Over the years I had collected a lot of data on the problem and had also developed treatment methods. So when I read an advertisement offering a research position, with some clinical work, I felt I had found a reasonable solution to my difficulties at the time.

Months passed and I was quite happy with the clinical work; but it was not like teaching. My contacts with the children were superficial, mainly because of their language, or lack of language, as that was my field. But they were never my children.

Zoo-boy.

Las patas de la mesa eran los barrotes de su jaula. Se balanceaba con los brazos por encima de la cabeza, como para protegerse. De un lado a otro, de un lado a otro. Un ayudante le instó a salir de debajo de la mesa, pero fue en vano.

Se balanceaba, adelante y atrás, adelante y atrás.

Yo le observaba desde detrás de la ventana-espejo.

<¿Cuántos años tiene?> le pregunté a la mujer de mi derecha.

<Quince.>

No se le podía decir más a un niño. Me apoyé en el cristal, para verle mejor. <¿Cuánto tiempo lleva aquí?> pregunté.

<Cuatro años>.

<¿Sin hablar nunca?>

<Sin hablar jamás.> La mujer levantó los ojos para mirarme, en la sombría oscuridad de aquella habitación tras el espejo.

<Sin dejar oír jamás el sonido de su voz.>

Me quedé mirándole un rato más. Luego recogí la caja con mi parafernalia y entré en la habitación del otro lado del espejo. El asistente se apartó de él cuando entré, y se alegró de marcharse. Oí cerrarse la puerta exterior, en el pasillo, y me di cuenta de que había ido a colocarse detrás del espejo, para observarnos. En la habitación nos quedamos solos, Zoo-boy y yo.

Con cautela, dejé la caja en el suelo. Esperé un momento, para ver si reaccionaba a la presencia de una nueva persona en la habitación; pero no reaccionó. Así que me acerqué. Me senté en el suelo, a un brazo de distancia de donde él estaba atrincherado bajo la mesa. Seguía meciéndose, agachado, con los brazos alrededor de las rodillas. No podía hacerme una idea de su estatura.

¿Kevin?

No reaccionó.

Sin saber muy bien qué hacer, miré a mi alrededor. Percibí la presencia de público detrás del espejo. Hablaban, allí dentro, voces indistintas, un murmullo tenue y ondulante, como el viento en los juncos en una tarde de verano. Pero yo sabía de qué sonido se trataba.

El niño no mostraba sus quince años. Aunque, acurrucado como estaba, no podía verlo bien, no parecía tan adulto. Yo le habría dado nueve años, tal vez. U once. No casi dieciséis.

Kevin, repetí, <me llamo Torey. ¿Recuerdas que la señorita Wendolowski te dijo que una persona iba a trabajar contigo? Esa persona soy yo. Soy Torey, y trabajo con personas que tienen problemas para hablar.>

Todavía meciéndose: se hubiera dicho que ni siquiera se dio cuenta de mi presencia. Había un pesado silencio a nuestro alrededor, apenas conmovido por el rítmico sonido de su cuerpo contra el linóleo del suelo.

Empecé a hablarle, con voz suave y acariciadora, como la que se usa con un cachorro asustado. Le conté por qué había venido, las cosas que haría con él, los niños con los que había trabajado felizmente. Le hablé de mí. Lo que dije no importaba, sólo el tono.

No hubo reacción. Se balanceó, nada más.

Pasaron los minutos. Empecé a no saber ya qué decir. No era fácil mantener una conversación unilateral como aquella, pero lo que lo hacía aún más difícil no era tanto Zoo-boy como la presencia de aquellos fantasmas al otro lado del espejo. Era fácil sentirse estúpido hablando solo cuando había media docena de personas invisibles mirando. Al final saqué la caja de mi parafernalia y cogí un libro de bolsillo, una historia de detectives sobre un niño y su amigo. Ahora te leeré un cuento, le dije a Zoo-boy, así nos sentiremos un poco más cómodos.

<Capítulo uno. El largo camino.>

Leí.

Y volví a leer.

En la esfera del reloj giraba el minutero.

De vez en cuando se oía el sonido amortiguado de una puerta que se abría y se cerraba, más allá del espejo. Se iban, uno a uno. Allí dentro no ocurría nada por lo que mereciera la pena perder la tarde.

Yo no leía mucho. La historia no era convincente.

Y Zoo-boy no hacía más que rockear.

Seguí leyendo. Y contando cuántas veces se abría y cerraba la puerta. ¿Cuántas personas habían entrado en la habitación detrás del espejo? No lo recordaba con exactitud.

¿Seis? ¿Siete? ¿Y cuántas habían salido ya? ¿Cinco?

Seguí leyendo.

Clic-clic. Otro se había ido.

Clic-clic. Y ya eran siete.

Seguí leyendo. Mi voz se había convertido en el único sonido de la habitación. Levanté la vista. Zoo-boy había dejado de mecerse. Lentamente, bajó los brazos para verme mejor. Sonrió. No era tonto. También había contado.

Me hizo un gesto con la cabeza, un pequeño movimiento dentro de los límites de la mesa y las sillas.

<¿Qué?> pregunté, pues no entendía lo que intentaba comunicarme.

Volvió a asentir, esta vez más ampliamente. Pero no era un simple gesto. Era una frase, más bien, por así decirlo, un período de gestos.

Yo seguía sin entender. Moví una silla para ver mejor, pero tuve que pedirle que repitiera.

Había algo que quería que yo supiera. Los suyos eran gestos poéticos, en sus remolinos y espirales apremiantes. Una danza de las manos. Pero no eran los signos de un lenguaje que yo conociera, el de los signos utilizados por los sordomudos o el del alfabeto de las manos. No lo entendía.

De debajo de la mesa salió un profundo suspiro. Me hizo una mueca. Luego, pacientemente, volvió a repetir sus gestos, esta vez con mayor lentitud y énfasis, como cuando se dirige a un niño ligeramente mudo. Y el hecho de no poder hacerse entender le desanimaba.

Al final se dio por vencido. Nos sentamos en silencio, mirándonos fijamente.

Yo aún tenía el libro en la mano; así que, en un intento desesperado por llenar ese vacío, le pregunté si quería que siguiera leyendo. Asintió con la cabeza.

Me apoyé en la pared. <Capítulo cinco. Fuera de la cueva.>

Zoo-boy movió a duras penas la otra silla de la mesa y se inclinó hacia delante para tocarme los vaqueros. Levanté la vista.

Tenía la boca abierta y se tiraba de la mandíbula inferior hacia abajo con una mano. Se señaló la garganta. Luego, abatido, sacudió la cabeza.

Hacía poco más de un año que trabajaba en aquella clínica como psicólogo investigador. Había dedicado la mayor parte de mi vida profesional a la enseñanza. Había desempeñado todas las funciones posibles en ese campo, desde la enseñanza en escuelas primarias normales hasta la enseñanza en universidades, desde la enseñanza en escuelas innovadoras con horarios de trabajo flexibles hasta la enseñanza en clases cerradas en el pabellón pediátrico de una institución mental estatal. Me encantaba enseñar.

Siempre me había gustado, y me sigue gustando. Pero con el paso de los años, los conceptos pedagógicos generales, sobre todo en el campo de la educación especial, habían empezado a cambiar, y ahora me sentía como una extraña en ese mundo.

Así que decidí hacer un doctorado en educación especial. No sé exactamente por qué. El título, en sí mismo, no me interesaba mucho; era una cualificación demasiado alta para volver a enseñar en una escuela. Y no había otros aspectos, en el campo de la educación, que me interesaran.

Desde luego, nunca quise ocupar cargos administrativos. Así que seguí adelante y estudié. En definitiva, creo que era una forma de hacer algo mientras decidía qué rumbo tomar en mi vida más adelante.

En el fondo de mi corazón esperaba que el péndulo de la pedagogía volviera a oscilar y que pudiera volver a la enseñanza sin comprometer mis convicciones.

Pero durante esos cuatro años de estudio, el cambio no se produjo, y me encontré, brutalmente, ante la disyuntiva de obtener mi diploma y cerrar la puerta de la escuela tras de mí para siempre, o dejarlo todo a medias e intentar hacer otra cosa. Al final opté por esta segunda alternativa, porque no podía soportar la idea de no volver nunca más a la enseñanza. Así que dejé Minneapolis y la universidad sin nada que demostrar de mis cuatro años de estudio.

Durante todo ese tiempo había estado investigando un fenómeno psicológico poco conocido, el mutismo electivo. Se trata de un trastorno emocional que se da principalmente en niños. El niño es físicamente capaz de hablar, pero por razones psicológicas se niega a hacerlo. Muchos de estos niños hablan realmente con alguien, normalmente miembros de su familia en casa, pero se vuelven deliberadamente mudos ante todos los demás. A lo largo de los años había recopilado muchos datos sobre el problema y también había desarrollado métodos de tratamiento. Así que cuando leí un anuncio en el que se ofrecía un puesto de investigador, con algo de trabajo clínico, me pareció que había encontrado una solución razonable a mis dificultades de entonces.

Pasaron los meses y estaba bastante contenta con el trabajo clínico; pero no era como la enseñanza. Mis contactos con los niños eran superficiales, principalmente por su lenguaje, o falta de lenguaje, ya que ese era mi campo. Pero nunca fueron mis hijos.

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks!