Today I want to introduce you to a book that is a little different from the usual. Actually, I would like to introduce you to an author who is a little different from all the others, but I started this blog with the intention of presenting books and I will be consistent with myself by choosing one of her works to represent the others. Not that I can't come back and present the others later, but I would like to do a trial run with different authors first to give space to all those who have come into my life, a sort of par condicio to be clear!

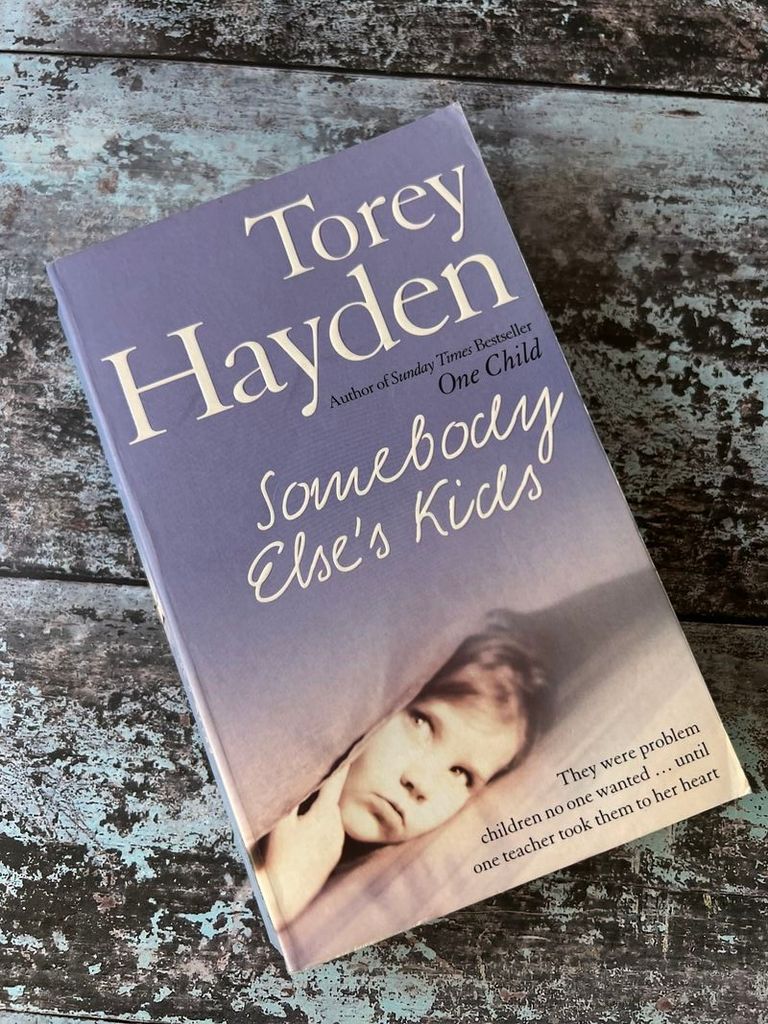

The book I am going to present to you is ** Someone Else's Kids by Torey Hayden.**

A seven-year-old boy who cannot speak except to repeat the weather forecasts and the words of others, a charming seven-year-old girl who cannot read or write because of a head injury caused by her father, a violent ten-year-old boy who saw his stepmother kill his father and brother and who moves from one family to another, a very shy twelve-year-old girl expelled from school because she is pregnant... No one but the miracle teacher had wanted to take care of them. No one had tried to understand them and help them face life. A poignant book in which Torey Hayden aims to confront the horrendous reality of abused children).

I know I said I am not here to introduce the author, but an introduction here is in order: Torey Hayden is an American child psychologist and support teacher, as well as being active in numerous other activities in the field of education. In most of her books, Torey Hayden recounts her personal experiences of helping children with different kinds of problems in school, which earned her the nickname ‘miracle teacher’.

Someone Else's Kids is one of the many true stories Torey tells us. I don't know if it's just a professional distortion, but I find these books uniquely beautiful, not only because of the author's skill as a novelist, but also because of what I consider to be a noble intent, which is to make these children known to everyone, to help understand them and not to write them off as ‘unmanageable’, because everyone has a story, everyone carries something inside, no child is born to be a problem.

Let us therefore return to Someone Else's Kids and its plot:

‘Take four children of different ages and with different histories and very different problems. Put them in a single classroom with a teacher who comes to care deeply for each of them. Essentially this is what happened when special teacher Torey Hayden took over ‘the class that created itself’. First came Boo, a seven-year-old boy with severe autism. Then came Lori, also seven years old, a victim of brain trauma as a result of physical abuse. Then came Tomaso, ten years old, who had taken care of other people and this had hurt him so much that he was determined to hurt others and make them hate him. Finally came Claudia, the bright and capable 12-year-old upper middle-class girl who had had to leave her private Catholic school when it was discovered that she was pregnant. This is a tale of the horrific reality of abused children, but also of the extraordinary possibilities for recovery that psychology, sensitivity and love can open up.’

To those who decide to get to know Someone Else's Kids , I also invite you to consult the author's website (the link to which, as always, can be found at the end of the article), where you will also find news about how these children, now adults, live today.

If even one person decides to understand and read this or another of Torey Hayden's books, I will know that the time spent creating this blog will not have been wasted.

Hoy quiero presentarles un libro un poco diferente de lo habitual. En realidad, me gustaría presentaros a una autora un poco diferente a todas las demás, pero empecé este blog con la intención de presentar libros y voy a ser consecuente conmigo misma eligiendo una de sus obras para representar a las demás. No es que no pueda volver y presentar a los demás más adelante, pero me gustaría hacer primero una prueba con autores diferentes para dar espacio a todos los que han entrado en mi vida, ¡una especie de par condicio para entendernos!

El libro que os voy a presentar es **Someone Else's Kids ** de Torey Hayden.

Un niño de siete años que no sabe hablar más que para repetir las previsiones meteorológicas y las palabras de los demás, una encantadora niña de siete años que no sabe leer ni escribir debido a una lesión en la cabeza causada por su padre, un violento niño de diez años que vio cómo su madrastra mataba a su padre y a su hermano y que va de una familia a otra, una niña muy tímida de doce años expulsada del colegio porque está embarazada... Nadie, salvo el profesor milagro, había querido ocuparse de ellos. Nadie había intentado comprenderles y ayudarles a enfrentarse a la vida. Un libro conmovedor en el que Torey Hayden pretende enfrentarse a la horrenda realidad de los niños maltratados).

Sé que he dicho que no estoy aquí para presentar al autor, pero no está de más una introducción: Torey Hayden es un psicólogo infantil estadounidense y profesor de apoyo, además de participar activamente en otras muchas actividades en el campo de la educación. En la mayoría de sus libros, Torey Hayden relata sus experiencias personales ayudando a niños con distintos tipos de problemas en la escuela, lo que le valió el apodo de «profesora milagro».

Hijos de Nadie es una de las muchas historias reales que nos cuenta Torey. No sé si se trata de una deformación profesional, pero estos libros me parecen singularmente bellos, no sólo por la habilidad de la autora como novelista, sino también por lo que considero una noble intención, que es dar a conocer a estos niños a todo el mundo, ayudar a comprenderlos y no tacharlos de «inmanejables», porque todos tienen una historia, todos llevan algo dentro, ningún niño nace para ser un problema.

Volvamos, pues, a Someone Else's Kids y a su argumento:

«Coged a cuatro niños de edades diferentes y con historias diferentes y problemas muy distintos. Póngalos en una misma clase con un profesor que llega a preocuparse profundamente por cada uno de ellos. En esencia, esto es lo que ocurrió cuando el profesor especial Torey Hayden se hizo cargo de «la clase que se creó a sí misma». Primero llegó Boo, un niño de siete años con autismo grave. Después llegó Lori, también de siete años, víctima de un traumatismo cerebral como consecuencia de malos tratos físicos. Luego llegó Tomaso, de diez años, que había cuidado de otras personas y esto le había hecho tanto daño que estaba decidido a herir a los demás y hacer que le odiaran. Por último llegó Claudia, la brillante y capaz niña de 12 años de clase media alta que había tenido que abandonar su colegio católico privado cuando se descubrió que estaba embarazada. Este es un relato de la horrible realidad de los niños maltratados, pero también de las extraordinarias posibilidades de recuperación que pueden abrir la psicología, la sensibilidad y el amor.»

A quienes decidan conocer Hijos de Nadie, les invito también a consultar la página web de la autora (cuyo enlace, como siempre, se encuentra al final del artículo), donde también encontrarán noticias sobre cómo viven hoy estos niños, ya adultos.

Si aunque sólo sea una persona decide comprender y leer éste u otro de los libros de Torey Hayden, sabré que el tiempo dedicado a crear este blog no habrá sido en vano.

The class created itself.

There is an old law of physics about Nature's horror of the void. That autumn, it seemed, Nature had sprung into action. There must have been a void that we had not noticed, because suddenly, without anyone having planned anything, a class began to form. The vacuum did not fill suddenly, as it sometimes does, but slowly, as it does every time Nature creates something great.

In August, at the beginning of the school year, I was working as a support teacher in a primary school. Children with major learning difficulties would leave their class for half an hour a day and come to me, alone or in groups of two or three. My job was to keep them as much as possible up to speed with their class, especially in reading and maths, but sometimes in other subjects as well. A class of my own, however, I did not have.

I had worked in that school district for six years, four of which I had devoted to teaching in a closed class, as the educators called it: a class that took place in a single classroom, where the children could not interact with the other pupils in the school. At that time I was teaching children with severe emotional instability problems. Then came Law 94- 142, known as the Integration Law, which aimed to place special school pupils in an environment that was as closed as possible and to reduce their deficiencies as much as possible with additional classes, the support classes. Closed classes, where special children were kept at a distance from normal ones, would disappear. And so the classifications would disappear. What a beautiful law. What beautiful ideals. And meanwhile, my children and I were trapped in reality.

When the law was passed, my closed class was dismantled. My eleven pupils, together with forty other severely handicapped people in the district, were integrated into normal classes. Only one special full-time class remained open, the one for the severely retarded, children who could not walk, talk or have control over physiological functions.

I was assigned a support class in a school on the other side of town, the same one to which my special class had belonged. This had happened two years earlier. Perhaps I should have realised the void that was being created. Maybe I shouldn't have been surprised when I saw that void closing.

I was unwrapping my lunch, a Big Mac from MacDonald's, a real feast, for me, since in the half-hour lunch break I certainly didn't have time to get in my car and drive across town to get a hamburger, as I used to do when I taught at my old school. Bethany, a school psychologist, had brought this to me. She understood my burger addiction.

I was just pulling my burger out of the styrofoam container, being very careful not to let out the avalanche of lettuce, as always happened to me, and trying, for the umpteenth time, to remember that idiotic little song that goes: Two patties of pure beef...> I wasn't thinking about work.

<Torey?>

I looked up. Birk Jones, district director of special classes, towered over me, his unlit pipe hanging from his lips. I was so focused on my burger that I hadn't even heard him enter the teachers' lounge.

<Oh, hello, Birk.>

<Do you have a minute?>

<Yeah, sure>, I said, even though I really didn't. I only had a quarter of an hour left to gobble down my burger and fries, drink my Dr. Pepper, and get back to the pile of ungraded homework waiting for me in class. The lettuce slipped out of the Big Mac and fell onto my fingers.

Bethany moved her chair and Birk sat between the two of us.

<I have a little problem, and I was hoping you could help me solve it>, she said.

<Yeah? What kind of problem?>

He took the pipe out of his mouth and scrutinised the cooker. <Seven years old, I suppose.> He uncovered his teeth. <He's in Marcy Cowen's kindergarten. A boy. Autistic, I think. You know, pirouettes, whirligigs Talk to himself. The same things your kids used to do. Marcy can't take it anymore. She had him in class last year too, for a while, and the child didn't improve at all, even with the help of a qualified assistant. We have to change technique with him.>

I continued to chew my burger. <And what could I do, me, to help you?

<Well...> Long pause. He looked at me so intently as I ate that I thought perhaps I should offer him some of my burger. <Well, Tor, I thought... maybe we could get him to come over here.>

<What do you mean? >

You could take care of it.>

<Me, take care of him?> A fry stuck in my throat.

<I'm not equipped to deal with autistic children right now, Birk.>

He wrinkled his nose and leaned towards me, confidentially. You could do it. Don't you think?> He paused, to see if I was responding or choking to death on my chip. <He would only come for half a day. In kindergarten she takes the regular classes. And in Marcy's class he doesn't do anything. I thought maybe you could give him special lessons. Like you did with the other kids you had.>

<But, Birk... I don't have that class anymore. I teach study subjects now. What about the kids in my support group?>

He shrugged his shoulders affably. <We'll sort them out somehow.>

The boy would arrive every day at 12.40. Until two o'clock, taking turns, there would also be other children in the classroom, but then it would be just him and me, with half the school day ahead of us. Birk's idea was that even if he destroyed my classroom, during the support hours with the other children, it would not be any worse than if he destroyed Marcy Cowen's kindergarten. Having worked for years in closed classes, I possessed that mysterious thing Birk called experience. Translated, it simply meant that nothing could disturb me any more.

I prepared the room for the boy's arrival. I put the fragile objects away, put all the toys made of small pieces that he could have swallowed in a cupboard, and moved the desks and tables so that I could have a more intimate contact with him than I usually had to have with my pupils in the support classes.

When the work was done, I took a step back to assess the work, and my heart widened. Teaching support classes was not particularly rewarding. I missed the closed classroom. I wished I still had my own class, with my own children. But above all, I missed that mysterious joy that working with emotionally unstable children always gave me.

On Monday of the third week in September I met Boothe Birney Franklin. His mother also called him Boothe Birney when she addressed him. His little sister, three years old, could only pronounce Boo. I thought that might be enough for me too.

Boo was seven years old. He was a magical child, as my children often seemed magical to me. In his expression was the same deceptive concreteness as in dreams. The son of a mixed couple, he had milk-tea coloured skin. His hair was a huge mass of soft, almost black curls. His eyes were green, a hazy, mysterious sea green, delicate and iridescent. He looked like something out of a Tasha Tudor picture book. He wasn't very grown up, for a seven-year-old. I would have given him five, maybe, no more.

His mother pushed him into the classroom, said a few words and left. Boo, now, belonged to me.

La clase se creó sola.

Hay una vieja ley de la física sobre el horror de la Naturaleza al vacío. Aquel otoño, al parecer, la Naturaleza había entrado en acción. Debía de haber un vacío del que no nos habíamos percatado, porque de repente, sin que nadie hubiera planeado nada, empezó a formarse una clase. El vacío no se llenó de repente, como ocurre a veces, sino lentamente, como ocurre cada vez que la Naturaleza crea algo grande.

En agosto, a principios de curso, trabajaba como profesora de apoyo en un colegio de primaria. Los niños con grandes dificultades de aprendizaje dejaban su clase durante media hora al día y venían a verme, solos o en grupos de dos o tres. Mi tarea consistía en mantenerlos lo más al día posible con su clase, sobre todo en lectura y matemáticas, pero a veces también en otras asignaturas. Sin embargo, yo no tenía clase.

Había trabajado en ese distrito escolar durante seis años, cuatro de los cuales los había dedicado a enseñar en una clase cerrada, como la llamaban los educadores: una clase que tenía lugar en un aula única, donde los niños no podían interactuar con los demás alumnos del centro. En aquella época daba clase a niños con graves problemas de inestabilidad emocional. Luego vino la Ley 94- 142, conocida como la Ley de Integración, que pretendía colocar a los alumnos de escuelas especiales en un entorno lo más cerrado posible y reducir al máximo sus deficiencias con clases adicionales, las clases de apoyo. Las clases cerradas, en las que los niños especiales se mantenían a distancia de los normales, desaparecerían. Y así desaparecerían las clasificaciones. Qué hermosa ley. Qué bellos ideales. Y mientras tanto, mis hijos y yo estábamos atrapados en la realidad.

Cuando se aprobó la ley, mi clase cerrada fue desmantelada. Mis once alumnos, junto con otros cuarenta discapacitados graves del distrito, fueron integrados en clases normales. Sólo quedó abierta una clase especial a tiempo completo, la de los retrasados graves, niños que no podían andar, hablar o tener control sobre las funciones fisiológicas.

Me asignaron una clase de apoyo en una escuela al otro lado de la ciudad, la misma a la que había pertenecido mi clase especial. Esto había ocurrido dos años antes. Quizá debería haberme dado cuenta del vacío que se estaba creando. Quizá no debería haberme sorprendido cuando vi que ese vacío se cerraba.

Estaba desenvolviendo mi almuerzo, un Big Mac de MacDonald's, un auténtico festín, para mí, ya que en la media hora de la pausa para comer desde luego no tenía tiempo de coger el coche y cruzar la ciudad para comprarme una hamburguesa, como solía hacer cuando daba clase en mi antiguo colegio. Bethany, una psicóloga escolar, me lo había comentado. Ella entendía mi adicción a las hamburguesas.

Estaba sacando mi hamburguesa del recipiente de poliestireno, con mucho cuidado de que no saliera la avalancha de lechuga, como siempre me ocurría, e intentando, por enésima vez, recordar esa cancioncilla idiota que dice: Dos hamburguesas de pura carne de vacuno...> No pensaba en el trabajo.

¿Torey?>

Levanté la vista. Birk Jones, director de distrito de clases especiales, se alzaba sobre mí, con la pipa apagada colgando de los labios. Estaba tan concentrado en mi hamburguesa que ni siquiera le había oído entrar en la sala de profesores.

Oh, hola, Birk.>

¿Tienes un minuto?>

Sí, claro>, dije, aunque en realidad no lo tenía. Sólo me quedaba un cuarto de hora para engullir mi hamburguesa y mis patatas fritas, beberme mi Dr. Pepper y volver a la pila de deberes sin corregir que me esperaban en clase. La lechuga se salió del Big Mac y cayó sobre mis dedos.

Bethany movió su silla y Birk se sentó entre los dos.

Tengo un pequeño problema y esperaba que pudieras ayudarme a resolverlo>, dijo.

¿Sí? ¿Qué clase de problema?>

Se sacó la pipa de la boca y escrutó la cocina.

Siete años, supongo>, se descubrió los dientes. <Está en la guardería de Marcy Cowen. Un niño. Autista, creo. Ya sabes, piruetas, zigzagueos. Habla solo. Las mismas cosas que hacían tus hijos. Marcy no puede soportarlo más. Ella lo tuvo en clase el año pasado también, por un tiempo, y el niño no mejoró en nada, incluso con la ayuda de un asistente calificado. Tenemos que cambiar de técnica con él.>

Seguí masticando mi hamburguesa. <¿Y qué podría hacer yo, yo, para ayudarle?

Bueno...> Larga pausa. Me miró tan fijamente mientras comía que pensé que tal vez debería ofrecerle un poco de mi hamburguesa. <Bueno, Tor, pensé...> ...que tal vez podríamos hacer que viniera aquí.

¿Qué quieres decir?>

Tú podrías encargarte de él.>

¿Yo, ocuparme de él?> Una patata frita se atascó en mi garganta.

No estoy equipado para tratar con niños autistas ahora mismo, Birk.>

Arrugó la nariz y se inclinó hacia mí, confidencialmente. <Tú podrías hacerlo. ¿No crees?

Hizo una pausa, para ver si respondía o me ahogaba con mi patata frita. <Sólo vendría medio día. En la guardería va a las clases normales. Y en la clase de Marcy no hace nada. Pensé que tal vez podrías darle clases especiales. Como hiciste con los otros niños que tuviste.>

Pero, Birk... Ya no tengo esa clase. Ahora enseño materias de estudio. ¿Y los chicos de mi grupo de apoyo?

Se encogió de hombros afablemente. Los arreglaremos de alguna manera.>

El niño llegaba todos los días a las 12.40. Hasta las dos, por turnos, también habría otros niños en el aula, pero luego estaríamos solos él y yo, con la mitad de la jornada escolar por delante. La idea de Birk era que aunque destrozara mi aula, durante las horas de apoyo con los otros niños, no sería peor que si destrozara el jardín de infancia de Marcy Cowen. Habiendo trabajado durante años en clases cerradas, yo poseía esa cosa misteriosa que Birk llamaba experiencia. Traducido, significaba simplemente que ya nada podía perturbarme.

Preparé la habitación para la llegada del niño. Guardé los objetos frágiles, puse en un armario todos los juguetes hechos de piezas pequeñas que podría haberse tragado, y moví los pupitres y las mesas para poder tener con él un contacto más íntimo que el que habitualmente tenía que tener con mis alumnos en las clases de apoyo.

Cuando terminé el trabajo, di un paso atrás para evaluarlo y se me ensanchó el corazón. Dar clases de apoyo no era especialmente gratificante. Echaba de menos el aula cerrada. Deseaba seguir teniendo mi propia clase, con mis propios hijos. Pero, sobre todo, echaba de menos esa misteriosa alegría que siempre me dio trabajar con niños emocionalmente inestables.

El lunes de la tercera semana de septiembre conocí a Boothe Birney Franklin. Su madre también le llamaba Boothe Birney cuando se dirigía a él. Su hermana pequeña, de tres años, sólo sabía pronunciar Boo. Pensé que eso también sería suficiente para mí.

Boo tenía siete años. Era un niño mágico, como a menudo me parecían mágicos mis hijos. En su expresión había la misma engañosa concreción que en los sueños. Hijo de una pareja mixta, tenía la piel del color de la leche. Su pelo era una enorme masa de rizos suaves, casi negros. Sus ojos eran verdes, de un misterioso verde marino brumoso, delicado e iridiscente. Parecía sacado de un libro ilustrado de Tasha Tudor. No era muy adulto para tener siete años. Yo le habría dado cinco, quizá, no más.

Su madre lo empujó al aula, dijo unas palabras y se fue. Boo, ahora, me pertenecía.

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks!