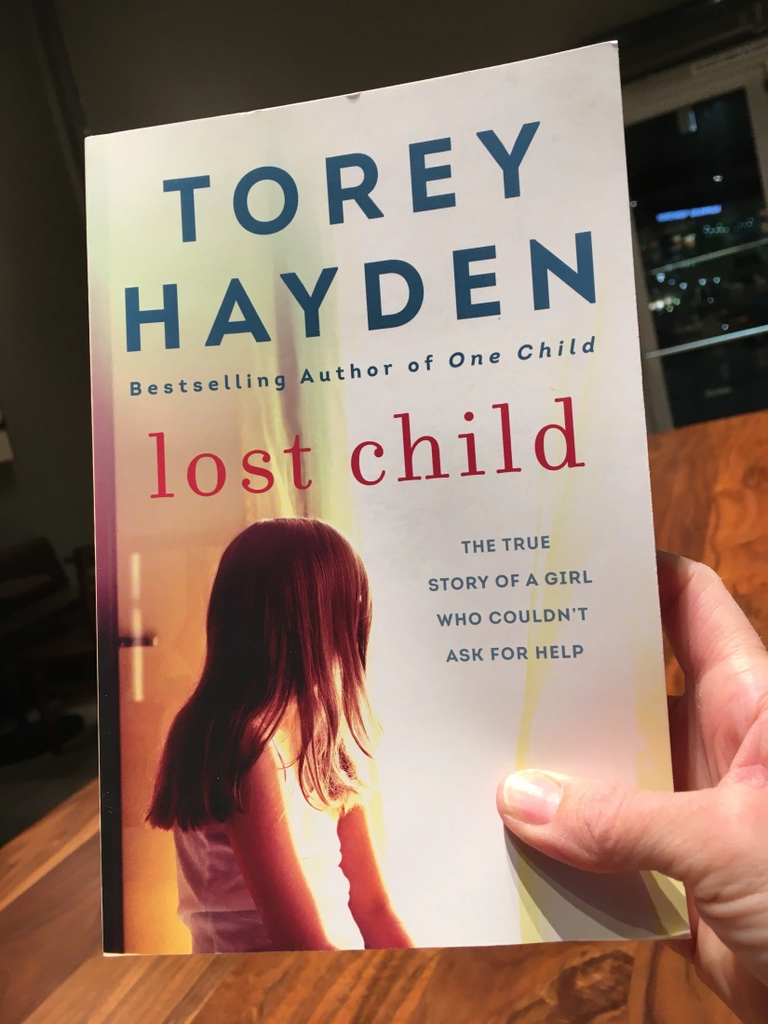

The appeal of Torey Hayden's novels is linked to a winning combination of pleasant, conversational, lively prose and plots derived from her real-life work experiences as a special teacher or child psychologist dealing with difficult and seemingly unsolvable cases. Over time, I have also read her pure fiction novels, but I have never found them as effective.

Now, as an adult, I felt the same enthusiasm and the same desire to continue reading when I picked up, after years of waiting, the new instalment, A lost child (that's all, if there is any objection to be made to the author). is precisely related to the lack of originality of the titles, which is also found in the original language, probably due to the precise desire to create an impression of seriality or recurrence, but which in Italian definitely loses its impact).

Even in this case, which dates back to the 1990s, Torey finds himself dealing with a particularly problematic situation. In fact, his friend Meleri, a social worker, introduces him to Glan Morla, a shelter for children with serious behavioural problems, and here she entrusts him with little Jessie Williams to begin therapy. Jessie is nine years old and, although her family situation is apparently much less disordered than that of the other guests at the centre, she suffers from a severe attachment disorder. Despite a long experience accumulated between the United States and England, Torey finds himself displaced by the child, who displays destabilising and sometimes disturbing attitudes: obsessed by a desire to be in control, Jessie is brash, manipulative and vindictive. She tells lies with extraordinary ease and for incongruous reasons, making them so believable and detailed that it is almost impossible to distinguish them from the truth. She seeks physical contact with a misplaced insistence and presumption of intimacy and is frankly opposed to any therapeutic activity proposed to her. But Jessie is also an incredibly intelligent child, perfectly capable of reading the behaviour of others and using it to her own advantage, and she has a great artistic talent: it is precisely her tiny, highly detailed and vividly coloured larks that trigger her professional and human career. nature of the psychologist, who sees an unexpressed potential behind it.

In reality, larks are small and dull birds to look at, no more colourful than a sparrow and only slightly larger. Their beauty lies in their song. However, there was something about Jessie's colourful style that captured it all... the bright feathers and the trill. (p. 46)

What makes the volume interesting is the attention, which seems to me greater than in previous writings, to the theoretical framework and the state of scholarship on therapy, analysed in a close comparison between the different interpretations of the profession and the ways forward, but also between the American reality (more medicalised and equipped, but also more tied to private and economic interests) and the English one (perhaps less wealthy, but welfare-oriented and more attentive to those in need). Torey's choices, as well as those of the other professionals dealing with Jess, always oscillate between need and real possibilities, which are above all economic possibilities and which reveal a long way to go in the development of English social services. institutions (’ various charitable institutions, large and small, did what they could to compensate for the deficiencies, but it was not enough. [...] It was not so much a question of the superiority of one culture over another, but rather of having to choose the lesser of two scenarios of sad circumstances’, p. 130, 131).

Perhaps also because of the external limits the system has to deal with, Jessie seems to be making little progress and Torey, during their Tuesday meetings, struggles to frame her and achieve some stable results. Things get complicated when one day the little girl makes serious accusations of bullying against one of the centre's managers, a man and professional with seemingly solid integrity. Torey finds herself deeply divided: on the one hand, the duty to take the girl's words seriously, especially given the existence of clear signs of a trauma of a sexual nature rooted in the more or less distant past; the desire to believe in an apparently good man who could see his existence ruined by the lies of a serial liar. The problem is conceptual and seemingly hopeless: ‘how can we know when a liar is telling the truth? ‘ (p. 95).

Bringing the truth to light is a long road, full of obstacles and destined to get lost several times in a labyrinth of mirrors. The writer succeeds in outlining the long times of therapy, the continuous dead ends, the uncertainties and doubts of a profession that cannot have definitive answers. However, thanks to perseverance and a strong spirit, it is possible to build a relationship of trust with the lost child, to convince him that it is possible to trust the adult world without being hurt by it, to escape from dysfunctional dynamics that seem destined to iterate endlessly and to colour the world with one's eyes as one can do with small coloured larks.

Once again, Torey L. Hayden does not disappoint his loyal readers with a story that smacks of truth and will, with the linearity and effectiveness of his prose, be able to attract new ones.

El atractivo de las novelas de Torey Hayden está ligado a una combinación ganadora de prosa agradable, dialogada y vivaz, y tramas derivadas de sus experiencias laborales reales como profesora especial o psicóloga infantil que se ocupaba de casos difíciles y aparentemente irresolubles. Con el tiempo, también he leído sus novelas de pura ficción, pero la verdad es que nunca las he encontrado tan efectivas.

Ahora, ya adulta, sentí el mismo entusiasmo y el mismo deseo de seguir leyendo cuando cogí, después de años de espera, la nueva entrega, Una niña perdida (eso es todo, si hay que hacerle alguna objeción al autor). está precisamente relacionado con la falta de originalidad de los títulos, que también se encuentra en el idioma original, probablemente debido al deseo preciso de crear una impresión de serialidad o recurrencia, pero que en italiano pierde definitivamente su impacto).

Incluso en este caso, que se remonta a los años 1990, Torey se encuentra lidiando con una situación particularmente problemática. De hecho, su amiga Meleri, trabajadora social, le presenta Glan Morla, un centro de acogida para niños con graves problemas de conducta, y aquí le confía a la pequeña Jessie Williams para que inicie la terapia. Jessie tiene nueve años y, aunque su situación familiar aparentemente es mucho menos desordenada que la del resto de huéspedes del centro, sufre un grave trastorno de apego. A pesar de una larga experiencia acumulada entre Estados Unidos e Inglaterra, Torey se ve desplazado por la niña, que presenta actitudes desestabilizadoras y a veces perturbadoras : obsesionada por el deseo de tener el control, Jessie es descarada, manipuladora y vengativa. Dice mentiras con extraordinaria facilidad y por razones incongruentes, haciéndolas tan creíbles y detalladas que es casi imposible distinguirlas de la verdad. Busca el contacto físico con una insistencia y presunción de intimidad fuera de lugar y se muestra francamente opositora a cualquier actividad terapéutica que se le proponga. Pero Jessie es también una niña increíblemente inteligente, perfectamente capaz de leer el comportamiento de los demás y utilizarlo en su propio beneficio, y tiene un gran talento artístico: son precisamente sus diminutas alondras de colores, muy detalladas y vivaces, las que desencadenan su carrera profesional y humana. naturaleza del psicólogo, que ve un potencial no expresado detrás de ello.

En realidad, las alondras son pájaros pequeños y aburridos a la vista, no son más coloridos que un gorrión común y sólo un poco más grandes. Su belleza reside en su canto. Sin embargo, había algo en el estilo colorido de Jessie que lo capturaba todo... las plumas brillantes y el trino. (pág. 46)

Lo que hace interesante el volumen es la atención, que me parece mayor que en escritos anteriores, al marco teórico y al estado de los estudios en torno a la terapia, analizados en una estrecha comparación entre las diferentes interpretaciones de la profesión y los caminos a seguir, pero también entre la realidad americana (más medicalizada y equipada, pero también más ligada a intereses privados y económicos) y la inglesa (quizás menos rica, pero orientada al bienestar y más atenta a los necesitados) . Las elecciones de Torey, así como de los demás profesionales que tratan con Jess, oscilan siempre entre la necesidad y las posibilidades reales, que son ante todo posibilidades económicas y que revelan un camino aún largo por recorrer en el desarrollo de los servicios sociales ingleses. instituciones (" varias instituciones caritativas, grandes y pequeñas, hicieron lo que pudieron para compensar las deficiencias, pero no fue suficiente. [...] No se trataba tanto de la superioridad de una cultura sobre otra, sino más bien de tener que elegir el menor de los males entre dos escenarios de tristes circunstancias ”, p. 130, 131).

Quizás también debido a los límites externos con los que tiene que lidiar el sistema, Jessie parece estar haciendo pocos avances y Torey, durante sus reuniones de los martes, lucha por encuadrarla y lograr algunos resultados estables. Las cosas se complican cuando un día la pequeña hace graves acusaciones de acoso contra uno de los responsables del centro, un hombre y profesional con una integridad aparentemente sólida. Torey se encuentra profundamente dividida: por un lado, el deber de tomar en serio las palabras de la niña , sobre todo teniendo en cuenta la existencia de signos claros de un trauma de naturaleza sexual arraigado en un pasado más o menos lejano; el deseo de creer en un hombre aparentemente bueno y que podría ver su existencia arruinada por las mentiras de un mentiroso en serie . El problema es conceptual y aparentemente sin salida: “ ¿cómo podemos saber cuándo un mentiroso está diciendo la verdad? ”(pág. 95).

Sacar la verdad a la luz es un camino largo, lleno de obstáculos y destinado a perderse varias veces en un laberinto de espejos . El escritor consigue esbozar los largos tiempos de la terapia, los continuos callejones sin salida, las incertidumbres y dudas de una profesión que no puede disponer de respuestas definitivas . Sin embargo, gracias a la perseverancia y a un espíritu fuerte, es posible construir una relación de confianza con el niño perdido , convencerlo de que es posible confiar en el mundo adulto sin ser herido por él, escapar de dinámicas disfuncionales que parecen destinadas a iterar sin cesar y colorear el mundo con la mirada como se puede hacer con pequeñas alondras de colores.

Una vez más, Torey L. Hayden no decepciona a sus fieles lectores con una historia que huele a verdad y que podrá, con la linealidad y eficacia de su prosa, atraer a otros nuevos.

Chapter 1

It was March when I saw the first lark. Not the animal, of course. On our moors, so high and windswept, it is too early at that time of year. The one I'm talking about was drawn on an A4 sheet of paper, the common kind you put in printers, and at first glance I honestly missed the bird completely. Meleri stretched out a hand and pointed to the bottom right-hand corner. I put on my reading glasses and lifted the paper towards the car window, and then I noticed a drawing that could not have been bigger than my thumbnail. The weather was typically Welsh that day, the sky was very overcast and there was that sort of water vapour too light to be drizzle, and too heavy to be mist, and the back seat of the car was as dark as the inside of an abandoned chapel. On the sheet, the tiny bird was crouched between blades of prickly-looking grass, its beady eyes, its shrewd expression as if it knew something I was unaware of. The brightly coloured feathers seemed to belong to a macaw rather than a lark. Tiny musical notes rose along the right margin to indicate its song.

‘Don't you think she shows some talent?’ asked Meleri. ‘The child is only nine years old.’

‘What is her name? You told me but I can't remember.’

‘Jessie. Jessie Williams.’

The minute details of the drawing, so precise and intricate, had mesmerised me.

Meleri opened the rubber band folder she held on her lap and pulled out three more, which she then handed to me. Two were in felt-tip pen, like the one I already had. The other in pencil, and the strokes were so clear and spider-web-like that I could hardly distinguish them in that little light. And in each was the same little bird, staring at me.

‘I like that you draw them,’ Meleri said. ‘They look cheerful to me. Like Jessie still has hope.’

I had met Meleri Thomas a few years earlier. In Cardiff, in the dressing room of a television studio on the Welsh-language channel S4C, where we had both been invited to appear on the morning show. I was there to promote a book, while she was participating in a debate on children's rights. She had immediately caught my attention, but would have had that effect on anyone. The marked, attractive, somewhat Italian features - big, elongated eyes, dark hair - the knitted dress of a striking emerald green that enveloped the figure. All striking features in themselves, not to mention Meleri's striking resemblance to the popular TV chef Nigella Lawson. For a split second I thought it was her, and wondered curiously why she should appear on a Welsh children's rights show.

Dressing rooms always put me on my toes. More or less all people waiting to be in front of the cameras feel anxiety for one reason or another, and the consequence is that, even if you don't know each other, it is normal for people in that situation to talk about more or less, to distract themselves from their nervousness. It had been a real challenge for me on that occasion because they all spoke Welsh. I had only just studied it, and I was not fluent. To be precise, my American language still didn't get along with the pronunciation of some words. Therefore, the only real memory of that day is related to my mispronunciation. The weather is always a good topic for a casual chat, and I had thought about saying how much I enjoyed the crisp cold days we were having at the time. In the unexpected hilarity that followed my remark, I discovered that the Welsh word for ‘frost’ is pronounced in a very similar way to the word for ‘sex’.

I had then seen Meleri again at a small conference for social workers and youth support workers, also in Cardiff. I had immediately recognised the black hair that flowed down her back and the glamorous attire. We'd laughed, remembering my embarrassing gaffe, and I'd had to admit that my Welsh had deteriorated in the meantime, having moved to an area whose dialect was very different. If I still read it quite well, I had, however, stopped speaking it.

‘But that's my area,’ she had told me, as I explained. ‘I live there!’ And then: ‘Well, if we are so close you must definitely come to Glan Morfa. I have a lot of children I would like to show you.’

Only two years later, I found myself driving along a very urbanised waterfront, which continued from one coastal town to the next, to reach the children's home in Glan Morfa.

The area was disused, starting from the abandoned industrial harbour, built for mines that are no longer active, to the desolate and melancholic tourist beach, with its broken roller coasters and barred kiosks. And then endless kilometres of campsites, rows upon rows of faded and rust-stained caravans, all empty because it was not the season.

The car took a one-way lane that passed between two of these caravan parks. The road surface was full of potholes, so we had to slow down to a walking pace. In truth, we took so many jolts that we couldn't help laughing in the back seat, because we were being tossed around left and right, at least until we found a grove of sparse trees deformed by the wind blowing in from the sea, through which a low, elongated building appeared. The bare, brutal architecture made me think of a 1960s building. The white paint around the windows was coming off. The rough plaster walls were the colour of porridge. Meleri sensed my dismay at such a grim scenario, and said, ‘Let's hope the council can afford to repaint it this year, although I think they intend to use the money for street resurfacing.

Inside, however, there was a totally different world. The entrance was well lit, painted in different shades of turquoise. There were posters and photographs pinned to a notice board showing group activities and outings. At the other end was a glass-enclosed office, where there was a calendar, individual cards and numerous photographs of children on the walls. Meleri introduced me to Joseph and Enir, members of the staff in charge.

Immediately upon my entrance, Enir turned on the electric kettle, took out four cups and poured instant coffee into each one. ‘Milk?’ he asked, adding it without waiting for my answer. Joseph opened a purple, round tin can and revealed assorted biscuits. ‘Got lucky,’ he told me cheerfully. ‘There are Penguin bars left.’ He handed me one.

We spent a very pleasant quarter of an hour getting to know each other. Enir was twenty-eight years old. She had worked in the family home for four, liked the shifts because they fitted in well with her still young daughter's school schedule, and was looking forward to leaving for Majorca that summer. Joseph seemed to have recently passed forty. He had worked at Glan Morfa for almost a decade, longer than anyone else, and had become the day manager. He liked it. He realised that for many it was not a career, but for him it was. He was happy to ‘be on the front line’, to use his own expression, happy to help the children who came to Glan Morfa grow and change during their stay there. He tried to give them a sense of belonging, to make each one feel that there was someone there who cared for them, and evidently over the years he had succeeded, as several ‘graduates’ - children who had reached the age of eighteen and had left the Social Services system - still came back regularly to visit him.

After coffee, Meleri and Joseph escorted me down a corridor adjacent to the office, and from there into a small room full of furniture. Two brown armchairs and two small filing cabinets were leaning against one wall, while against the opposite wall was a beige sofa with lined fabric. In the middle - barely leaving room to turn around - was a bulky wooden table with a white formica top, and next to it were four orange plastic chairs.

‘It's not luxurious,’ Joseph announced. He did not use the tone of someone who wants to justify himself; I found him matter-of-fact, and that was all. ‘But it is our therapy room. Maybe I should put that label in inverted commas, because it's also the conference room, the interview room, the must-get-out-of-this-kid's-chaos-and-get-to-talk-to-him room, and, as you can see, it also serves as storage.’

Meleri had gone to get Jessie, so I took a chair to the right of the table and sat down.

A few minutes later the door opened and I saw her come in with a little girl. ‘Here's Jessie,’ she said. And then, ‘Jessie, meet Torey.’

The little girl greeted me with an affectionate, friendly smile.

She was cute, looking a bit old-fashioned, though this was perhaps only due to her clothing. Instead of the leggings and colourful jumpers that were the norm for girls her age, Jessie wore a clean cotton dress and a beige cardigan that wouldn't have been out of place in the 1970s. Her hair was straight, reaching almost to her shoulders, soft red, parted on one side, and held back from her face with a bobby pin. Her eyes were a deep green. She was petite, showing less than her years.

‘Hello,’ I said to her. ‘Would you like to sit down?’ I pointed to the chair right in front of me, being the one closest to her.

Jessie did not take it. Instead, she went around the table and pulled out the one next to mine, but did not sit down. She stopped and looked at me. A long, appraising look.

‘I donated my hair,’ she affirmed. ‘That's why it's not very long. It used to come in here.’ He pointed to a spot in the middle of my arm. ‘But then I cut it off and now they will make a wig out of it for a little girl who lost it because she has cancer.’

‘A very kind gesture on your part,’ I replied, in the face of that unexpected information.

‘They grow on me fast.’

‘You did a good thing. And now, if you'd like to sit down. Maybe Mrs Thomas can stand there on the couch if she wants, and you can take that chair. I brought some things with me that we can do together.’

She made not the slightest effort to move from where she was. ‘Yours are nice. Can I touch them?’

Before I had time to answer, she had already done so. ‘Very nice.’

‘Thank you.’

‘They're curly. Like a movie star's. Are you a movie star? Because they look like one of those actresses you see in movies.’

I don't have star hair. My hair, which I had always considered ‘full-bodied’ when I lived in the dry climate of Montana, had become a mass of cabbage vines in the humidity of Wales. Most of the time it made me think of sheep's wool.

Jessie pulled a curl, stretching it out to its full length and applied enough tension to make it a not entirely appropriate gesture. Her gaze did not waver. 'You could donate the hair. It's long enough. Have you thought about it?’

‘I think it's a little too curly.’

‘It's a kind gesture. Donate the hair. You should do it.’

‘Thanks, I'll think about it,’ I said, and began to feel on the wrong side of that conversation.

‘My guess is you're a movie star,’ Jessie continued, ’that's why you don't want to donate it.’

‘Thanks for the compliment, but would you mind letting them go? Because you're pulling them a little too much.’

Jessie maintained eye contact, and a hint of a smile that felt like defiance curved her lips. She was in control, and she knew it. And she knew I knew it.

‘Would you mind sitting down?’ I asked her again.

‘You have a strange voice.’

‘Yes, don't I? It's because of my accent. American. Why don't you sit down?’

‘What's this?’ He let go of the lock and bent over the table to pick up the folder I had brought with me. I used to call it the ‘box of tricks’ because at first I was literally walking around with a big box full of pens, paper, puppets, playing cards and other things that children find funny. Now I found that bag much more practical.

Jessie unfastened the clasp and looked inside. Her eyes lit up. 'Hey! You've got Staedtler markers. And they've never been opened! They still have the sticker on the cap. I use them. I draw. Do you have papers in there?’

I put a hand in front of the opening of the folder. ‘Let's talk a little first. Let's get to know each other.’

‘Why?’ was his reply.

‘Because I think it might help? No?’

‘No.’ She pulled a marker out of the packet and began to draw a picture on her forearm.

‘No, not like that,’ I said, taking it from her fingers.

Meleri, who had placed herself on the couch behind us, leaned forward and said, ‘You will have many more opportunities to draw. Torey will visit you every week.’

‘Why?’ asked the little girl.

‘We think it would be good for you to have someone just for you, to help you solve some of the things that give you problems,’ Meleri answered her.

‘I don't have problems,’ she did. There was no defiant tone. If anything, she seemed to want to apologise, almost as if she felt sorry for me, that I had come all that way without needing to.

‘Let's take a moment to get to know each other,’ I proposed. ‘Tell me what things interest you.’

‘These.’ He pointed to the markers.

‘Yes, you like to draw, am I right? What else do you like?’

Jessie shrugged exaggeratedly. ‘I don't know.’

‘Let's start with the... from the ice cream. What's your favourite?’

‘I'm lactose intolerant,’ she replied.

‘Jessie,’ Meleri intervened. ‘That's false.’

‘Actually, it's true. It gives me diarrhoea. You just don't know it.’

‘Never mind,’ I did. ‘What about the TV? What's your favourite show?’

Jessie exhaled, dramatically. ‘Can I use those markers now?’

On the table, right in front of me, was the folder with her lark drawings; I opened it and pulled out the first one. ‘Ms Thomas showed me your masterpieces. I love the colours you used for the lark.’

Another frustrated sigh, and then she dropped forward, resting her forehead on the table. ‘Geee-up,’ he muttered under his breath.

‘And I know you'd like to start using those markers right away.’

‘Well, yes,’ he said, his lips against the tabletop. Without detaching his forehead from the ant, he barely turned and raised his left arm to look at Meleri. ‘But is he always like that?’ he asked, expressionless. We both burst out laughing, and I suspect that was his intent.

Eventually he pulled himself up to his seat, grabbed the drawing and held it in front of his face. ‘I did it for Idris,’ he explained. ‘Give me a pen and I'll write his name on it. That way everyone will know it's for him.’

‘Who is Idris?’ I asked.

‘My brother. He is eighteen years old. He lives in Switzerland, but he's coming next week to take me out. We're going to Rhyl. To the amusement park. So give me a pen. So I can write his name in it. I really did it for him. You shouldn't have it. That's the problem with this place. That they keep taking my drawings, when I want to keep them for my family.’

‘Jessie, what you say is not true,’ Meleri intervened.

‘Yes, it is. Look, you have all my stuff inside this folder. They're my drawings. I didn't make them for you.’

‘No, Jessie, what's fake is your brother. You don't have a brother living in Switzerland. And you're not going to Rhyl.’

‘Yes I do have a brother,’ he said, cuttingly.

‘No, you don't. Please. We've talked about this before. Many times. Remember the Progress Project? The part about making up stories?’ asked Meleri of her.

'I have a brother. Only you don't know anything about him. He got killed when I was just a little girl.’

‘Jessie...’ said Meleri, a note of warning in her voice.

‘He was in a nightclub, went out for a cigarette and some bad people came. They shot him in the head and then put his body in a coffin.’

‘Jessie, please,’ Meleri warned her again. ‘You know the rules. You'll get the time out.’

Jessie cast me a sidelong glance with a smirk and shrugged lightheartedly, as if it was all a game.

Not knowing at that point how to resume the conversation, I handed her the markers.

Her eyes lit up. She opened the packet again with a snap, and counted them aloud to make sure there were twenty. She took out a dark green one, and brought the skylark drawing in front of her. He turned it over, showing the white back, and tested the marker by making two dashes. One by one he took all the others and did the same thing.

‘I want to do it right,’ he said, ’so Idris will be proud of me.’ He took the paper and assessed the coloured marks by bringing his eyes closer to them, tilting them in one direction and another under the pale light of the neon lamps, as if those marks had vital importance. Then she put it down, and turned it back to the side of the drawing, lifting the box of markers. She looked at them for a long time, sternly, and my feeling was that she was deciding what to do. I could almost perceive her thoughts, but I had no idea what would come next. Her actions were strangely detached, as if every single thing was done in a context unknown to me. The ordinary steps of writing or drawing on paper were missing. They were simply not there.

He again chose the dark green felt-tip pen, the first one he had picked up, studied it again and then suddenly began to doodle, moving his hand jerkily, violently.

My first instinct was to stop her, because she was ruining the beautiful lark, but I held back and let her. Back and forth, back and forth, broad, agitated strokes. Shortly afterwards she began to pant, as if she was exerting herself.

I glanced at Meleri, above her head. She widened her eyes to indicate how bizarre she found that behaviour, but the cognizance in her gaze told me that it was not the first time she had witnessed such a thing.

For three or four minutes Jessie went on like this, until she had filled the whole sheet. The lark, the meadow she stood in, the musical notes rising from the side... it had all disappeared under the dark green ink. Eventually Jessie pulled back, breathing heavily, and let her hands drop to her sides. ‘I hope you have another paper.’

I nodded, uncertain.

‘That one I had to scribble down.’

‘I wonder... maybe you were angry because we said Idris's story was false, and you tried to take the drawing away from us?’

‘Nah,’ he replied, indifferent. ‘I just wanted to bring out the devil in me.’

‘What do you mean?’ I asked her.

‘Mrs Thomas didn't tell you?’ she did, pointing at Meleri with a nod from over her shoulder.

‘Told her what?’

‘That I'm possessed. I'm waiting for the exorcist to come.’

‘No, he hasn't told me. Because I'm pretty sure Mrs. Thomas doesn't believe it. And I don't believe it either.’

‘That's OK,’ Jessie replied, cheerfully. ‘You don't have to believe things to make them true.’

Capítulo 1

Era marzo cuando vi la primera alondra. No el animal, por supuesto. En nuestros páramos, tan altos y azotados por el viento, es demasiado pronto en esa época del año. La alondra de la que hablo estaba dibujada en una hoja de papel A4, de las que se ponen en las impresoras, y a primera vista, sinceramente, no vi el pájaro por completo. Meleri extendió una mano y señaló la esquina inferior derecha. Me puse las gafas de leer y levanté el papel hacia la ventanilla del coche, y entonces me fijé en un dibujo que no podía ser más grande que la uña de mi pulgar. Aquel día hacía un tiempo típicamente galés, el cielo estaba muy nublado y había esa especie de vapor de agua demasiado ligero para ser llovizna y demasiado denso para ser niebla, y el asiento trasero del coche estaba tan oscuro como el interior de una capilla abandonada. Sobre la sábana, el diminuto pájaro estaba agazapado entre briznas de hierba de aspecto espinoso, sus ojos brillantes, su expresión sagaz como si supiera algo que yo ignoraba. Las plumas de colores brillantes parecían más propias de un guacamayo que de una alondra. Pequeñas notas musicales se elevaban a lo largo del margen derecho para indicar su canto.

«¿No crees que demuestra cierto talento?», preguntó Meleri. «La niña sólo tiene nueve años».

«¿Cómo se llama? Me lo dijiste pero no lo recuerdo» >.

«Jessie. Jessie Williams.» >

Los minuciosos detalles del dibujo, tan precisos e intrincados, me habían hipnotizado.

Meleri abrió la carpeta elástica que tenía sobre el regazo y sacó tres más, que luego me entregó. Dos eran de rotulador, como el que ya tenía. El otro a lápiz, y los trazos eran tan claros y como telarañas que apenas podía distinguirlos con aquella lucecita. Y en cada uno estaba el mismo pajarito, mirándome fijamente.

«Me gusta que los dibujes», dijo Meleri. «Me parecen alegres. Como si Jessie aún tuviera esperanza».

Había conocido a Meleri Thomas unos años antes. En Cardiff, en el camerino de un estudio de televisión del canal en galés S4C, donde ambas habíamos sido invitadas a aparecer en el programa matinal. Yo estaba allí para promocionar un libro, mientras ella participaba en un debate sobre los derechos de los niños. Ella había captado inmediatamente mi atención, pero habría tenido ese efecto en cualquiera. Los rasgos marcados, atractivos, algo italianos -ojos grandes y alargados, pelo oscuro-, el vestido de punto de un llamativo verde esmeralda que envolvía la figura. Todos rasgos llamativos en sí mismos, por no hablar del asombroso parecido de Meleri con la popular chef televisiva Nigella Lawson. Por una fracción de segundo pensé que era ella, y me pregunté con curiosidad por qué aparecería en un programa galés sobre los derechos de los niños.

Los camerinos siempre me ponen alerta. Más o menos todas las personas que esperan estar delante de las cámaras sienten ansiedad por una razón u otra, y la consecuencia es que, aunque no se conozcan, es normal que la gente en esa situación hable de más o de menos, para distraerse de su nerviosismo. Para mí había sido todo un reto en aquella ocasión porque todos hablaban galés. Yo acababa de estudiarlo y no lo dominaba. Para ser precisos, mi idioma americano aún no se llevaba bien con la pronunciación de algunas palabras. Por lo tanto, el único recuerdo real de aquel día está relacionado con mi mala pronunciación. El tiempo siempre es un buen tema para una charla informal, y se me había ocurrido decir lo mucho que me gustaban los días frescos y fríos que estábamos teniendo en aquel momento. En la inesperada hilaridad que siguió a mi comentario, descubrí que la palabra galesa para «escarcha» se pronuncia de forma muy parecida a la palabra «sexo».

Volví a ver a Meleri en una pequeña conferencia para trabajadores sociales y personal de apoyo a los jóvenes, también en Cardiff. Reconocí inmediatamente el pelo negro que le caía por la espalda y el glamuroso atuendo. Nos habíamos reído, recordando mi embarazosa metedura de pata, y yo había tenido que admitir que mi galés se había deteriorado entretanto, al haberme mudado a una zona cuyo dialecto era muy diferente. Si todavía lo leía bastante bien, sin embargo había dejado de hablarlo.

«Pero ésa es mi zona», me había dicho cuando se lo expliqué. «¡Yo vivo allí!». Y luego: «Bueno, si estamos tan cerca, tienes que venir sin falta a Glan Morfa. Tengo un montón de niños que me gustaría enseñarte».

Sólo dos años después, me encontré conduciendo por un paseo marítimo muy urbanizado, que continuaba de una ciudad costera a otra, para llegar al hogar infantil de Glan Morfa.

La zona estaba en desuso, empezando por el puerto industrial abandonado, construido para minas que ya no están activas, hasta la desolada y melancólica playa turística, con sus montañas rusas rotas y sus quioscos enrejados. Y luego interminables kilómetros de campings, filas y filas de caravanas descoloridas y manchadas de óxido, todas vacías porque no era temporada.

El coche tomó un carril de sentido único que pasaba entre dos de estos parques de caravanas. El firme estaba lleno de baches, así que tuvimos que reducir la velocidad a un ritmo de paseo. En realidad, dimos tantas sacudidas que no pudimos evitar reírnos en el asiento trasero, porque nos zarandeaban a diestro y siniestro, al menos hasta que encontramos una arboleda de árboles ralos deformados por el viento que soplaba desde el mar, a través de la cual apareció un edificio bajo y alargado. La arquitectura desnuda y brutal me hizo pensar en un edificio de los años sesenta. La pintura blanca alrededor de las ventanas se estaba desprendiendo. Las toscas paredes de yeso tenían el color de las gachas de avena. Meleri percibió mi consternación ante un panorama tan desolador y dijo: «Esperemos que el ayuntamiento pueda permitirse repintarlo este año, aunque creo que tienen intención de emplear el dinero en repavimentar las calles».

Dentro, sin embargo, había un mundo totalmente distinto. La entrada estaba bien iluminada y pintada en distintos tonos de turquesa. Había carteles y fotografías pegados en un tablón de anuncios que mostraban las actividades y salidas del grupo. En el otro extremo había un despacho acristalado con un calendario, tarjetas individuales y numerosas fotografías de niños en las paredes. Meleri me presentó a Joseph y Enir, los responsables.

Nada más entrar, Enir encendió el hervidor eléctrico, sacó cuatro tazas y vertió café instantáneo en cada una. «¿Leche?», preguntó, añadiéndola sin esperar mi respuesta. Joseph abrió una lata redonda de color morado y sacó galletas variadas. «He tenido suerte», me dijo alegremente. «Quedan barras de pingüino». Me dio una.

Pasamos un cuarto de hora muy agradable conociéndonos. Enir tenía veintiocho años. Llevaba cuatro trabajando en la casa familiar, le gustaban los turnos porque encajaban bien con el horario escolar de su hija, aún pequeña, y estaba deseando marcharse a Mallorca aquel verano. Joseph parecía haber pasado recientemente los cuarenta. Llevaba casi una década trabajando en Glan Morfa, más que nadie, y se había convertido en el encargado de día. Le gustaba. Se daba cuenta de que para muchos no era una carrera, pero para él sí. Se sentía feliz de «estar en primera línea», según su propia expresión, feliz de ayudar a los niños que venían a Glan Morfa a crecer y cambiar durante su estancia allí. Intentaba darles un sentimiento de pertenencia, hacer que cada uno sintiera que había alguien que se preocupaba por él, y evidentemente con los años lo había conseguido, ya que varios «graduados» -los niños que habían cumplido dieciocho años y habían abandonado el sistema de los Servicios Sociales- seguían volviendo regularmente a visitarle.

Después del café, Meleri y Joseph me acompañaron por un pasillo adyacente a la oficina, y de allí a una pequeña habitación llena de muebles. Dos sillones marrones y dos pequeños archivadores estaban apoyados contra una pared, mientras que contra la pared opuesta había un sofá beige de tela forrada. En el centro -apenas dejaba espacio para darse la vuelta- había una voluminosa mesa de madera con tablero de formica blanca, y junto a ella cuatro sillas de plástico naranja.

«No es lujoso», anunció Joseph. No empleó el tono de quien quiere justificarse; me pareció práctico, y nada más. «Pero es nuestra sala de terapia. Quizá debería poner esa etiqueta entre comillas, porque también es la sala de conferencias, la sala de entrevistas, la sala donde hay que salir del caos de este niño y hablar con él y, como puedes ver, también sirve de almacén.»

Meleri había ido a buscar a Jessie, así que cogí una silla a la derecha de la mesa y me senté.

Unos minutos después se abrió la puerta y la vi entrar con una niña. Aquí está Jessie», dijo. Y luego: «Jessie, te presento a Torey».

La niña me saludó con una sonrisa afectuosa y amistosa.

Era mona, parecía un poco pasada de moda, aunque quizá sólo se debiera a su vestimenta. En lugar de los leggings y los jerseys de colores que eran la norma para las niñas de su edad, Jessie llevaba un vestido limpio de algodón y una rebeca beige que no habría desentonado en los años setenta. Llevaba el pelo liso, que le llegaba casi hasta los hombros, de color rojo suave, con raya a un lado y recogido con una horquilla. Sus ojos eran de un verde intenso. Era menuda y no aparentaba la edad que tenía.

«Hola», le dije. «¿Quieres sentarte?» Señalé la silla que estaba justo delante de mí, por ser la más cercana a ella.

Jessie no la cogió. En cambio, rodeó la mesa y sacó la que estaba junto a la mía, pero no se sentó. Se detuvo y me miró. Una mirada larga y apreciativa.

Doné mi pelo», afirmó. «Por eso no es muy largo. Antes entraba aquí». Señaló un punto en medio de mi brazo. «Pero luego me lo corté y ahora le harán una peluca a una niña que lo perdió porque tiene cáncer».

«Un gesto muy amable por su parte», respondí, ante aquella información inesperada.

«Me crecen rápido».

«Has hecho algo bueno. Y ahora, si quiere sentarse. La Sra. Thomas puede quedarse de pie en el sofá si quiere, y tú puedes coger esa silla. He traído algunas cosas que podemos hacer juntas».

No hizo el menor esfuerzo por moverse de donde estaba. «Los tuyos son bonitos. ¿Puedo tocarlas?»

Antes de que tuviera tiempo de responder, ella ya lo había hecho. «Muy bonitos».

«Gracias».

«Son rizados. Como los de una estrella de cine. ¿Eres una estrella de cine? Porque se parecen a una de esas actrices que ves en las películas».

No tengo pelo de estrella. Mi pelo, que siempre había considerado «con cuerpo» cuando vivía en el clima seco de Montana, se había convertido en una masa de enredaderas de coles en la humedad de Gales. La mayor parte del tiempo me hacía pensar en lana de oveja.

Jessie tiró de un rizo, estirándolo en toda su longitud y aplicó la tensión suficiente para convertirlo en un gesto no del todo apropiado. Su mirada no vaciló. Podrías donar el pelo. Es lo bastante largo. ¿Lo has pensado?».

«Creo que es demasiado rizado».

«Es un gesto amable. Dona el pelo. Deberías hacerlo».

«Gracias, me lo pensaré», dije, y empecé a sentirme en el lado equivocado de aquella conversación.

«Supongo que eres una estrella de cine», continuó Jessie, “por eso no quieres donarlo”.

«Gracias por el cumplido, pero ¿te importaría soltarlos? Porque estás tirando de ellos demasiado».

Jessie mantuvo el contacto visual, y un atisbo de sonrisa que parecía desafío curvó sus labios. Ella tenía el control, y lo sabía. Y sabía que yo lo sabía.

«¿Te importaría sentarte?», volví a preguntarle.

«Tienes una voz extraña».

«Sí, ¿verdad? Es por mi acento. Americano. ¿Por qué no te sientas?»

«¿Qué es esto?» Soltó el candado y se inclinó sobre la mesa para coger la carpeta que yo había traído. Solía llamarla la «caja de trucos» porque al principio me paseaba literalmente con una gran caja llena de bolígrafos, papel, marionetas, naipes y otras cosas que a los niños les hacen gracia. Ahora esa bolsa me parecía mucho más práctica.

Jessie abrió el cierre y miró dentro. Se le iluminaron los ojos. Tienes rotuladores Staedtler. Y nunca se han abierto. Todavía tienen la pegatina en el capuchón. Yo los uso. Yo dibujo. ¿Tienes papeles ahí?»

Pongo una mano delante de la abertura de la carpeta. «Hablemos un poco primero. Conozcámonos».

«¿Por qué?», fue su respuesta.

«¿Porque creo que podría ayudar? ¿No?»

«No.» Sacó un rotulador del paquete y empezó a hacerse un dibujo en el antebrazo.

«No, así no», le dije, quitándoselo de los dedos.

Meleri, que se había colocado en el sofá detrás de nosotros, se inclinó hacia delante y dijo: «Tendrás muchas más oportunidades de dibujar. Torey te visitará todas las semanas».

«¿Por qué?», preguntó la niña.

«Creemos que sería bueno para ti tener a alguien sólo para ti, que te ayude a resolver algunas de las cosas que te dan problemas», le contestó Meleri.

«Yo no tengo problemas», respondió ella. No había tono desafiante. Si acaso, parecía querer disculparse, casi como si sintiera pena por mí, por haber llegado hasta allí sin necesidad.

«Tomémonos un momento para conocernos», le propuse. «Dime qué cosas te interesan».

«Éstas». Señaló los rotuladores.

«Sí, te gusta dibujar, ¿verdad? ¿Qué más te gusta?».

Jessie se encogió de hombros exageradamente. «No lo sé».

«Empecemos por el... de los helados. ¿Cuál es tu favorito?»

«Soy intolerante a la lactosa», contestó ella.

«Jessie», intervino Meleri. «Eso es falso».

«En realidad, es verdad. Me da diarrea. Sólo que no lo sabes».

«No importa», dije. «¿Y la tele? ¿Cuál es tu programa favorito?»

Jessie exhaló, dramáticamente. «¿Puedo usar esos rotuladores ahora?»

Sobre la mesa, justo delante de mí, estaba la carpeta con sus dibujos de alondra; la abrí y saqué el primero. «La señora Thomas me enseñó tus obras maestras. Me encantan los colores que has usado para la alondra».

Otro suspiro frustrado, y luego se dejó caer hacia delante, apoyando la frente en la mesa. «Geee-up», murmuró en voz baja.

«Y sé que te gustaría empezar a usar esos rotuladores ahora mismo».

«Pues sí», dijo, con los labios contra el tablero de la mesa. Sin despegar la frente de la hormiga, apenas se giró y levantó el brazo izquierdo para mirar a Meleri. «¿Pero siempre es así?», preguntó, inexpresivo. Los dos nos echamos a reír, y sospecho que ésa era su intención.

Al final se incorporó, cogió el dibujo y se lo puso delante de la cara. «Lo hice para Idris», explicó. «Dame un bolígrafo y escribiré su nombre en él. Así todos sabrán que es para él».

«¿Quién es Idris?», pregunté.

«Mi hermano. Tiene dieciocho años. Vive en Suiza, pero vendrá la semana que viene para llevarme de paseo. Iremos a Rhyl. Al parque de atracciones. Dame un bolígrafo. Para que pueda escribir su nombre en él. Realmente lo hice por él. No deberías tenerlo. Ese es el problema con este lugar. Que siguen llevándose mis dibujos, cuando quiero guardarlos para mi familia».

«Jessie, lo que dices no es verdad», intervino Meleri.

«Sí que lo es. Mira, tienes todas mis cosas dentro de esta carpeta. Son mis dibujos. No los hice para ti».

«No, Jessie, lo que es falso es tu hermano. No tienes un hermano viviendo en Suiza. Y no vas a ir a Rhyl».

«Sí tengo un hermano», dijo, cortante.

«No, no lo tienes. Por favor. Ya hemos hablado de esto antes. Muchas veces. ¿Recuerdas el Proyecto Progreso? ¿La parte de inventarse historias?», le preguntó Meleri.

Tengo un hermano. Sólo que no sabes nada de él. Lo mataron cuando yo era sólo una niña».

«Jessie...», dijo Meleri, con una nota de advertencia en la voz.

«Estaba en un club nocturno, salió a fumar un cigarrillo y llegó gente mala. Le dispararon en la cabeza y luego metieron su cuerpo en un ataúd».

«Jessie, por favor», volvió a advertirle Meleri. «Conoces las reglas. Tendrás el tiempo fuera».

Jessie me lanzó una mirada de reojo con una sonrisa burlona y se encogió de hombros despreocupadamente, como si todo fuera un juego.

Sin saber en ese momento cómo reanudar la conversación, le entregué los rotuladores.

Sus ojos se iluminaron. Volvió a abrir el paquete con un chasquido y los contó en voz alta para asegurarse de que había veinte. Sacó uno verde oscuro, y acercó el dibujo de la alondra frente a ella. Le dio la vuelta, mostrando el reverso blanco, y probó el rotulador haciendo dos rayas. Uno a uno cogió todos los demás e hizo lo mismo.

«Quiero hacerlo bien», dijo, “para que Idris esté orgulloso de mí”. Cogió el papel y evaluó las marcas de colores acercando los ojos a ellas, inclinándolos en un sentido y en otro bajo la pálida luz de las lámparas de neón, como si aquellas marcas tuvieran una importancia vital. Luego lo dejó en el suelo y lo volvió hacia el lado del dibujo, levantando la caja de rotuladores. Los miró durante largo rato, con severidad, y tuve la sensación de que estaba decidiendo qué hacer. Casi podía percibir sus pensamientos, pero no tenía ni idea de lo que vendría a continuación. Sus acciones eran extrañamente distantes, como si cada cosa se hiciera en un contexto desconocido para mí. Faltaban los pasos ordinarios de la escritura o el dibujo sobre papel. Sencillamente, no estaban ahí.

Volvió a elegir el rotulador verde oscuro, el primero que había cogido, lo estudió de nuevo y de repente empezó a garabatear, moviendo la mano espasmódicamente, con violencia.

Mi primer instinto fue detenerla, porque estaba arruinando la hermosa alondra, pero me contuve y la dejé. Adelante y atrás, adelante y atrás, movimientos amplios y agitados. Poco después empezó a jadear, como si estuviera haciendo un esfuerzo.

Miré a Meleri, por encima de su cabeza. Ella abrió los ojos para indicar lo extraño que le parecía aquel comportamiento, pero el conocimiento de su mirada me dijo que no era la primera vez que presenciaba algo así.

Jessie siguió así durante tres o cuatro minutos, hasta que llenó toda la hoja. La alondra, el prado en el que estaba, las notas musicales que surgían de un lado... todo había desaparecido bajo la tinta verde oscuro. Finalmente, Jessie se echó hacia atrás, respirando con dificultad, y dejó caer las manos a los costados. «Espero que tengas otro papel».

Asentí, inseguro.

«Ese lo tuve que garabatear».

«Me pregunto... ¿quizá te enfadaste porque dijimos que la historia de Idris era falsa, e intentaste quitarnos el dibujo?».

«No», respondió, indiferente. «Sólo quería sacar el diablo que llevo dentro».

«¿Qué quieres decir?», le pregunté.

«¿No te lo ha dicho la señora Thomas?», hizo, señalando a Meleri con un movimiento de cabeza por encima del hombro.

«¿Decirle qué?»

«Que estoy poseída. Que estoy esperando a que venga el exorcista».

«No, no me lo ha dicho. Porque estoy bastante seguro de que la señora Thomas no se lo cree. Y yo tampoco lo creo».

«No pasa nada», respondió Jessie, alegremente. «No hace falta creerse las cosas para que sean verdad».

Source image / Fuente imagen: Torey Hayden.

Mis Blogs y Sitios Web / My Blogs & Websites: