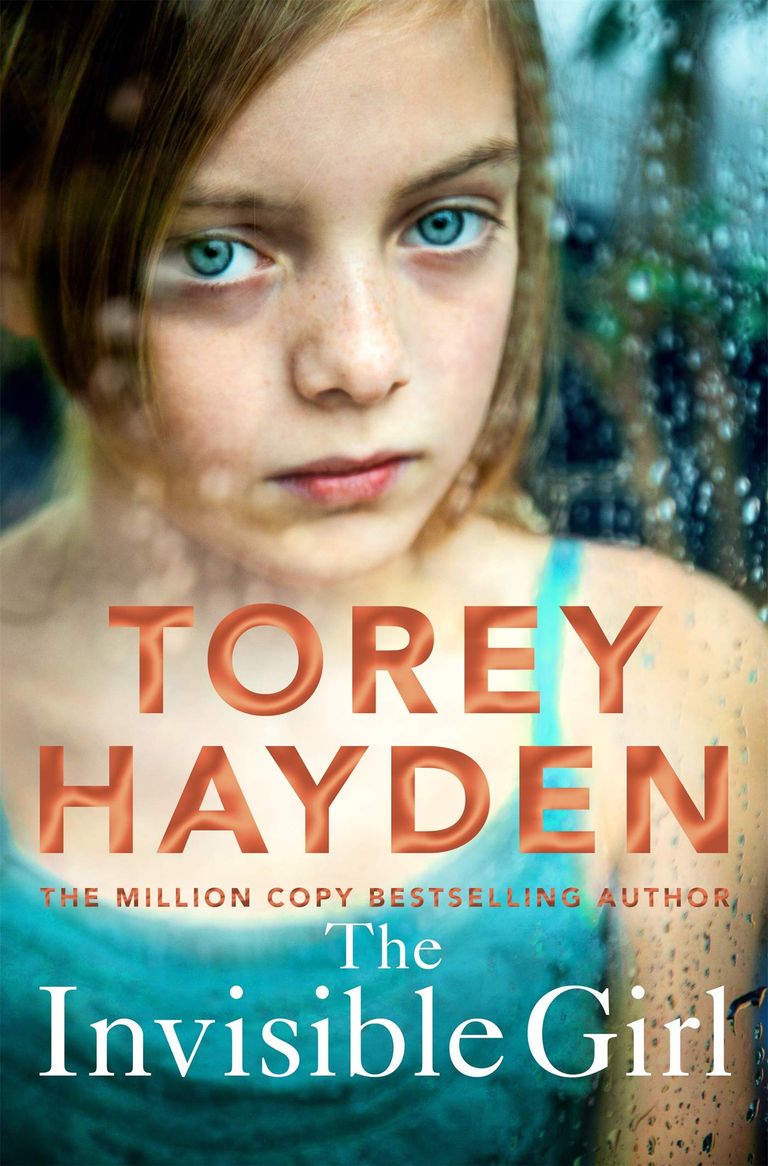

Torey L. Hayden, American, lives several years in England. His experience as a teacher in a special school for problematic children has led him to read a specialist in the field of child psychopathology. In Italy Corbaccio has published, with great critical and public success, Una bambina (17 editions), Come in a gabbia, La figlia della tigre, Una bambina e gli spettri, Figli di nessuno, Una di loro, Una bambina bellissima, Bambini in silence, La ragazza invisibile e I bambini di Torey Hayden written with Michael J. Marlowe, e i romanzi Il gatto meccanico, La foresta dei girasoli e L’innocenza delle volpi. Hayden's books are translated in many languages and have sold 25 million copies worldwide.

With her latest novel, The Invisible Girl, Torey Hayden once again recounts a case she has personally dealt with, a true story, as the book makes clear. Original title. In comparison with the previous A Lost Girl, the patient is not a child, but a teenager, marked by a history of abuse and abandonment within the family, and then by a succession of unsuccessful foster care.

The impact Torey's dealings with Eloise are rather abrupt: the girl comes to her without warning or appointment, interrupts a group session and tells her a confusing and implausible story. The inability to understand and accept boundaries is, after all, one of the characteristic features of the young woman, and not only within the therapeutic relationship. Meleri, the social worker who followed her case, informs Torey that Eloise had to leave her last foster family because of the obsessive attention she reserved for her eldest daughter, Heddwen, to whom she continued to return even after her estrangement, so that the scenario of a real bullying phenomenon is set up. Therefore, Torey is assigned the mission of following the girl and trying to help her with the tools and techniques of behavioral therapy. But, unfortunately, the resources that The resources the healthcare system makes available to her for treatment are limited and are met with resistance from Eloise, who tends to become defensive as soon as someone perceives a hint of her truth:

«For you I am nothing more than a case. A diagnosis, "A few boxes to tick and a damn file, that's all. You don't even see me. You think you see me, but you can't. The truth is, I'm as invisible to you as I am to anyone else." (p. 112)

On most occasions of confrontation, the girl is in opposition: she is willing to chat about irrelevant topics, and she closes herself off when you try to get to the heart of her experience or suggest activities that might help her open up. Torey soon realizes, with the sensitivity that characterizes his gaze, that the young woman carries within her a wound that is not clinically observable, but that continues to hurt, producing negative effects on her perception of the world, on her feelings. The world of The fantasies she debates, or the mysterious Olivia who keeps popping up in her conversations – alternately friend, comforter, fragile creature to be cared for – soon take shape as a strategy Eloise uses to protect herself from an outside world she perceives as violent, hostile. His need for care, for affection, he seeks in his imagination what has been denied to him in reality. Torey, who was a young woman with a very rich inner life and who drew strength and lymph from it to become a writer, cannot help but identify with her patient and uses, in an unorthodox therapeutic medium, her own personal experience to seek contact. with Eloise:

«People have strange ideas about imaginary worlds. They make you feel like there's something wrong with you because you have people in your mind that they can't meet, but I don't think that's a big deal. As long as we remember that there's a difference between what what is in our mind and what is outside. As long as we do not expect others to conform to what we have created. My imaginary world helped me survive a very difficult time in my life, and I can only thank it for that. We do what we have "what to do to avoid succumbing." (p. 153)

Despite the distancing from the usual procedures, which leads to some stumbling blocks that the psychologist never stops questioning from a self-analysis perspective, it is precisely this identification that ends up offering Eloísa a key to understanding what that happens to him and that sometimes seems to prevail even over his will.

The repetition of a typical structure of Hayden's works occurs again in this latest novel: the encounter with the patient, the taking of the reins, the search for strategies directed towards a confrontation with the other parties involved, a slow path towards some form of resolution and farewell, a glimpse of the future. However, compared to other procedural writings, in this one the author puts more into play her own experience, her background personal. While this creates greater involvement, it also runs the risk of giving the impression of less control by the therapist over what happens, as well as over Eloise's progress, creating a displacement effect.

However, there are some points to reflect on fundamental aspects for every educator: the importance of suspending judgment and not projecting one's own mental schemes and expectations onto the other; of knowing how to look at and listen to the person in front of us, both for what they say and for what they don't say; of admitting the possibility that an educational relationship has ups and downs, moments of stagnation, and that often the needs and desires of both parties do not coincide, forcing one to change methods and strategies to adapt to specific circumstances; the need, even, at a given moment, to let things happen.

Torey L. Hayden, americana, vive da molti anni in Inghilterra. La sua esperienza di insegnante nelle scuole speciali per bambini problematici ha fatto di lei una specialista nell’ambito della psicopatologia infantile. In Italia Corbaccio ha pubblicato, con grande successo di critica e di pubblico, Una bambina (17 edizioni), Come in una gabbia, La figlia della tigre, Una bambina e gli spettri, Figli di nessuno, Una di loro, Una bambina bellissima, Bambini nel silenzio, La ragazza invisibile e I bambini di Torey Hayden scritto con Michael J. Marlowe, e i romanzi Il gatto meccanico, La foresta dei girasoli e L’innocenza delle volpi. I libri di Hayden sono tradotti in molte lingue e hanno venduto 25 milioni di copie in tutto il mondo.

Con su última novela, La niña invisible, Torey Hayden vuelve a relatar un caso que ha tratado personalmente, una historia real, como deja claro el título original. En comparación con la anterior Una niña perdida, la paciente no es una niña, sino una adolescente, marcada por una historia de abusos y abandono en el seno de la familia, y luego por una sucesión de acogimientos sin éxito.

El impacto con Eloise es bastante brusco para Torey: la niña acude a ella sin previo aviso ni cita, interrumpe una sesión de grupo y le cuenta una historia confusa e inverosímil. La incapacidad para comprender y aceptar los límites es, después de todo, uno de los rasgos característicos de la joven, y no sólo dentro de la relación terapéutica. Meleri, la trabajadora social que siguió su caso, informa a Torey de que Eloise tuvo que abandonar a su última familia de acogida debido a la atención obsesiva que reservaba a su hija mayor, Heddwen, a la que seguía volviendo incluso después de su alejamiento, de tal forma que se configura el escenario de un auténtico fenómeno de acoso. Por ello, se asigna a Torey la misión de seguir a la niña e intentar ayudarla con las herramientas y técnicas de la terapia conductual. Pero, por desgracia, los recursos que el sistema asistencial pone a su disposición para el tratamiento son limitados y chocan con la resistencia de Eloise, que tiende a ponerse a la defensiva en cuanto alguien percibe un atisbo de su verdad:

«Para ti no soy más que un caso. Un diagnóstico, unas casillas que marcar y un maldito expediente, eso es todo. Ni siquiera me ves. Crees que me ves, pero no puedes. La verdad es que soy tan invisible para ti como para los demás». (p. 112)

En la mayoría de las ocasiones de confrontación, la chica se muestra contraria: tanto está dispuesta a charlar sobre temas irrelevantes, tanto se cierra en cuanto intentas llegar al meollo de su experiencia o sugerirle actividades que podrían ayudarla a abrirse.

Torey no tarda en darse cuenta, con la sensibilidad que caracteriza su mirada, de que la joven lleva dentro una herida que no es clínicamente observable, pero que sigue doliendo, produciendo efectos negativos en su percepción del mundo, en su sentir. El mundo de fantasías en el que se debate, o la misteriosa Olivia que sigue apareciendo en sus conversaciones - alternativamente amiga, consoladora, frágil criatura a la que hay que cuidar -, pronto toman forma como una estrategia que Eloise utiliza para protegerse de un mundo exterior que percibe como violento, hostil. Su necesidad de cuidados, de afecto, busca en su imaginación lo que se le ha negado en la realidad. Torey, que fue una joven con una vida interior muy rica y que sacó de ella fuerza y linfa para convertirse en escritora, no puede evitar identificarse con su paciente y utiliza, en un medio terapéutico poco ortodoxo, su propia experiencia personal para buscar el contacto con Eloise:

«La gente tiene ideas extrañas sobre los mundos imaginarios. Te hacen sentir que hay algo malo en ti porque tienes gente en tu mente que no pueden conocer, pero creo que no pasa nada. Siempre que recordemos que hay una diferencia entre lo que está en nuestra mente y lo que está fuera. Mientras no esperemos que los demás se ajusten a lo que hemos creado. Mi mundo imaginario me ayudó a sobrevivir en una época muy difícil de mi vida, y sólo puedo agradecérselo. Hacemos lo que tenemos que hacer para no sucumbir». (p. 153)

A pesar del distanciamiento de los procedimientos habituales, que conduce a algunos tropiezos sobre los que la psicóloga no deja de interrogarse en una perspectiva de autoanálisis, es precisamente esta identificación la que acaba ofreciendo a Eloísa una clave de comprensión de lo que le sucede y la que a veces parece prevalecer incluso sobre su voluntad.

La repetición de una estructura típica de las obras de Hayden vuelve a producirse en esta última novela: el encuentro con el paciente, la toma de las riendas, la búsqueda de estrategias dirigidas en un enfrentamiento con las otras partes implicadas, un lento camino hacia alguna forma de resolución y despedida, un atisbo de futuro. Sin embargo, en comparación con otros escritos procesales, en éste la autora pone más en juego su propia experiencia, su bagaje personal. Si bien esto genera una mayor implicación, también corre el riesgo de dar la impresión de un menor control por parte de la terapeuta sobre lo que sucede, así como sobre el progreso de Eloise, creando un efecto de desplazamiento.

Sin embargo, hay algunos puntos de reflexión sobre aspectos fundamentales para todo educador: la importancia de suspender el juicio y no proyectar en el otro los propios esquemas mentales y expectativas; de saber mirar y escuchar a quien tenemos enfrente, tanto por lo que dice como por lo que no dice; de admitir la posibilidad de que una relación educativa tenga altibajos, momentos de estancamiento, y que muchas veces las necesidades y deseos de ambas partes no coincidan, obligando a cambiar métodos y estrategias para adaptarse a circunstancias concretas; la necesidad, incluso, en un momento dado, de dejar hacer.

The chairs, very close together, were arranged in a circle. Each child stuck a sticker with the name of an emotion on the forehead of the closest classmate. Then, all together, the children would try to imitate that emotional state so that their partner, who couldn’t read it, could guess it. This therapeutic game was intended to help the little ones recognize and express various moods, but we called it the “Fool’s Game” among ourselves, because it caused so much hilarity.

It was Carly’s turn, and her word was “angry.” Seven years old and with Down syndrome, Carly was a curly-haired girl who danced around the circle of chairs, putting so much energy into it that her tag floated to the floor. But it didn’t matter, because she couldn’t read: she just picked it up and stuck it back on her forehead. “You dropped it again!” the other six children screamed as they competed to mime the word “angry,” and the general chaos increased.

When the door opened, I expected to see someone who worked in the offices and had come to ask us to keep it down. I hoped to accompany my apology with a polite explanation: this was the last time, because we were scheduled to be in the parish hall the following week. The children didn’t even notice and continued the game. After all, maybe it was no one. It was a windy day and the building was drafty. Maybe the door hadn’t closed properly and the wind had blown it open for a moment before slamming it shut. I continued to watch it, but when nothing happened, I turned my attention back to the children.

A few moments later, it opened a crack again. And this time I caught a glimpse of a peeping tom. But as I watched, the door slammed shut. It was time to investigate. When the children saw me stand up, the game stopped. I motioned for them to continue and went to see what was happening. “Is there anyone there?” I said, throwing the door open.

In the dimly lit hallway stood a hunched-over teenage girl with an oval face and long, unkempt blond hair. She was wearing a generic school uniform: white blouse, black cardigan and black trousers, but no tie, so it was impossible to tell which school she attended.

“Are you Torey?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“Mrs Thomas said she would help me.”

I raised my eyebrows, puzzled. I hadn’t spoken to Meleri for weeks and my association hadn’t alerted me to a new arrival. That day’s session was the only work I was doing for social services at the moment. The so-called “enrichment group” was for special needs children up to eight years old, from disadvantaged backgrounds. We met for an hour a week to work on interpersonal skills. No one had mentioned a teenager to me.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Eloise.”

“Eloise what?”

She was silent for a moment, clutching her shoulders imperceptibly, as if she had to think about it, and then she replied: “Eloise Jones.”

That moment of hesitation made me think she was reluctant to give her last name. Maybe she had made it up, but even if it were true, I couldn't tell much from it, given that a third of the people in that part of Wales are named Jones.

"There must have been a misunderstanding, because you're not on my schedule."

"Mrs. Thomas said she'd help me," she repeated.

I glanced at my watch. "I finish with this group at four-thirty. I'm free after that."

Her expression was unreadable. There was a sort of detachment, which made me feel as if I'd asked her pointless questions.

"I have to go back now," I said, not needing to imagine the chaos I'd find, because I could hear it. I swung the door wide open so the kids would know I was there.

"Can I wait?" Eloise asked.

"It's at least twenty minutes away."

"Never mind."

There was no reason to leave her in the hallway. We were playing in a group, so I agreed. “Okay,” and I went back into the room, followed by Eloise.

“Who is it?” asked one of the children.

“Yes, who is it?” exclaimed another from the opposite side.

“She’s a guest. Her name is Eloise. How do you greet a guest, Dylan? Do you shout ‘Who are you’ or do you say…?”

“I know! I know! I know! Ma’am, I know!” It was eight-year-old Sallie, who didn’t even disdain to push her way through the chairs to get to us. “How are you?” she said to Eloise. “Hello, what’s the weather like?” Sallie’s manners would have been a little more convincing if she didn’t have the word “disgust” plastered on her forehead.

There was a row of chairs lined up along the side wall, and I imagined Eloise would choose one of them to wait for me to finish with the group. But she followed me and sat with us in our circle.

The children seemed spellbound. Almost all too shy to speak to her, they danced back and forth, with no desire to resume the Fool’s Game. Only Dylan, a strapping seven-year-old with the physique of a miniature rugby player, had no such hesitations. “Who are you? Why are you here?”

I announced, “This is Eloise. She’s come to see us today.”

“But why?”

Answering that question was not easy, because I didn’t know either. “She’s come to see us, Dylan. That should be enough information for you.”

“Where are you from?” she asked.

“Please, Dylan, sit down,” I urged.

“Are you Welsh?” she insisted.

“Dylan...”

“T’ siarad Cymraeg?”

“Dylan...”

“I’d like to know if you’ll be part of this group. Will you be part of this group? Because you’re too big to be in this group. And there are enough girls already.”

“Stedd i lawr.” I stood up to make sure she obeyed and went to sit down. She stepped back and returned to her seat, but continued to eye Eloise suspiciously.

Realizing that we would not regain the concentration needed for the game, I decided to end with a story. I chose A Tiger at Teatime by Judith Kerr because of its intriguing plot, featuring a little girl and a female-looking tiger who appears out of nowhere in her home. I also chose it because of the key emotions it evokes: excitement and anxiety in particular. Who wouldn't be excited at the idea of welcoming a real tiger into their home? Who wouldn't be anxious?

I read the story and concluded by saying, "He was a very hungry tiger, wasn't he? What did he eat first?"

"People," Carly replied. "Tigers eat people."

"But the tiger in this story didn't eat anyone. What did he eat?"

"Tigers eat people," Carly insisted.

“They bought her tiger food,” Owen chimed in.

“In the end, they decided they would buy a tin of tiger food in case she ever saw them again,” I replied. “But when it came to tea time, they didn’t give her tiger food. What did they give her instead?”

Dylan snorted, “There’s no such thing as tiger food. You can’t go into a shop and buy a tin of tiger food.”

“What did they give her?” I asked again.

“Everything!” Sallie exclaimed. “Everything they had for snacks. And she drank it all, too. All her tea and orange juice and all her water, too.”

“Thanks,” I said, relieved that someone had at least heard me.

“I don’t think it’s possible to drink all the water in the tap,” Eloise chimed in.

Surprised, I looked at her.

The tap is connected to the water pipes. To empty the tap, the tiger would have to drink an entire aqueduct. This is not believable.

The children were as surprised as I was that Eloise had joined in the conversation. Mostly, I think, because it had never occurred to them how much water there might be, exactly, in their kitchen tap. I, on the other hand, had not expected her to join in, not least because this was a fantasy story about a tiger sitting down to tea with a little girl and her mother, and not a nature documentary.

“And she never once asked to go to the toilet,” added Sallie.

Finally, when the children had left, I turned to Eloise, who had remained in her chair in the circle. I sat down next to her. “Tell me what I can do for you.”

“I need to get back to my host family in Moelfre.”

Bewildered by the request, I observed, “It’s far from here.” Since I did nothing even vaguely related to transporting children around, I asked, “Could you explain a little more?”

Eloise looked away and barely huffed, looking a little frustrated, the way teenagers do when adults prove obtuse. Then she huffed again, as if reconsidering. “There was a big misunderstanding. About the ring. I hadn’t taken it. Seriously, I hadn’t taken it, but Olivia was mad, so I was forced to leave the Powells to go to that other place, which I hate. But it was just a misunderstanding. Olivia texted me to say she was sorry. You see, that boy, Sam, had given it to me. The ring, I mean. But it belonged to Olivia, and he had taken it, and now he’s realized it wasn’t me. That’s why I have to give it back to him, or else I’ll be in big trouble.”

I was lost. I didn’t know what to do. I knew absolutely nothing about this play or its characters. “Let’s take a step back. Did Mrs. Thomas tell you that I would help you?”

Eloise nodded. “She said that you write books. And that you help people.”

“Did she also explain how I could help you?”

Eloise nodded. “She said that you write books. And that you help people.”

“Did she also explain how I could help you?”

Another sigh of frustration, this time more impatient. “Not me. Mrs. Thomas said so. I explained that I had to return the ring to Olivia, and Mrs. Thomas said that she could help me because she writes books. So, please. That’s why I came. Please.”

I didn’t understand any of this story. A complete stranger comes to me and wants me to help her get back to her old foster family to return a piece of jewelry? It was like some weird community service version of Lord of the Rings.

“What school do you go to?” I asked.

“This has nothing to do with school,” Eloise replied.

I looked at her.

When she realised I wasn’t going to continue the conversation until she answered me, she said, “Ysgol Dafydd Morgan,” with an irritated sigh. I knew it was a secondary school in a coastal town about ten miles away.

“You couldn’t get there that quickly from Dafydd Morgan.”

Eloise widened her eyes to express how irritating she found it. “I took the bus.”

“Did you leave?” I insisted.

She shook her head. “No.”

“Did they give you permission to leave early?” I asked sceptically.

Her voice became pathetic. “Please. Please.”

I paused to think and silence enveloped us.

When I looked up, Eloise had lowered her eyes, giving me time to study her. There was nothing special about her appearance. Insignificant features, worldly blue-grey eyes, small mouth, thin lips. Long, wavy, light brown hair, which she probably wore tied up in class, loose over her shoulders. I imagined her as one of those children who sneak out of school unnoticed, and live on the fringes of life, always going unnoticed.

“Can you show me the ring?” I asked, mainly to check that it was really there.

She placed the small black bag she was carrying on her shoulder on her lap and opened it. At first she searched in vain, which made me immediately suspect that she had not told me the truth.

As if she sensed my disbelief, Eloisa seemed visibly distressed as she opened the bag further and began searching again.

“Wait a minute,” I said, “where did you get all these medicines?” Among the contents of the bag I glimpsed several packets of paracetamol.

Without answering, she quickly pushed the boxes to the bottom of the bag, hiding them with other things.

“No, wait. Let me see, please,” I insisted, holding out a hand. Eloisa resisted, clutching the bag to her body.

“Give me your bag, please.”

“It’s mine.”

“Yes, I know, but please give it to me.”

For a long moment she held the bag tightly to her chest. Our eyes met.

“Please give it to me,” I repeated.

Finally, with a sigh, she handed it to me.

I placed the bag on my lap and opened it. One, two, three, four, five boxes of paracetamol, sixteen tablets each. One could buy a maximum of two boxes—thirty-two tablets in total—to reduce the likelihood of death in the event of an overdose. Buying five boxes meant having a definite plan in mind, and for me that meant only one thing: suicide.

“What is all this?” I asked.

“It’s just headache pills.”

“It’s too many for a headache.”

“I suffer from migraines.”

“It’s too many even for a migraine.”

Desperation flashed across her face. “It’s not what it looks like,” she said.

“It’s too much medication to take all at once.”

The corners of her mouth turned down. Her chin trembled.

“Something serious has happened, hasn’t it?”

She nodded.

“Do you want to tell me?”

She shook her head.

“I’ll be happy to help you if I can, but I need to know what’s going on.”

Eloise shook her head again.

“What can I do to help you?” I asked.

“Please come with me to Moelfre.”

“I can’t do that. I’ll take you to school if you want. Or to Mrs. Thomas’s office.”

“No, I’d like to go home.”

“I don’t understand,” I objected. “Moelfre is definitely further up the road, and you go to Ysgol Dafydd Morgan, which is about twenty miles in the opposite direction. So I don’t think your home is in Moelfre.”

“Yes it is. And I need you to walk me there.”

“Let me phone Mrs. Thomas so I can understand better. In the meantime, let’s leave this here,” I said, picking up the paracetamol boxes.

“But don’t you understand?” Eloise moaned. “I have to get back to Olivia. I have to take her ring.” She waved her hands frantically, almost as if she wanted to hit herself, but she didn’t. Crossing her arms tightly against her chest, she harpooned her shoulders, swinging them back and forth.

She stepped forward.

I felt a pang of fear. I knew nothing about the girl, but I sensed self-destruction in her behavior and problems far greater than having to return a ring to someone.

Torey Hayden's Invisible Girl shows us worlds and wounds beyond human sight.

Las sillas, muy juntas, estaban dispuestas en círculo. Cada niño pegaba una pegatina con el nombre de una emoción en la frente del compañero más cercano. Luego, todos juntos, los niños intentaban imitar ese estado emocional para que su compañero, que no podía leerlo, lo adivinara. Aquel juego terapéutico pretendía ayudar a los pequeños a reconocer y expresar diversos estados de ánimo, pero entre nosotros lo llamábamos el «Juego de los Tontos», porque provocaba mucha hilaridad.

Era el turno de Carly, y su palabra era «enfadada». Con siete años y síndrome de Down, Carly era una niña de pelo rizado que bailaba en medio del círculo de sillas poniendo tanta energía en ello que su etiqueta se quedaba flotando en el suelo. Pero poco importaba, porque ella no sabía leer: se limitaba a recogerla y pegársela de nuevo en la frente. «¡Se te ha vuelto a caer!», chillaron los otros seis niños que competían por hacer la mímica de la palabra “enfadado”, y el caos general aumentó.

Cuando se abrió la puerta, esperaba ver a alguien que trabajaba en las oficinas y que había venido a pedirnos que hiciéramos menos ruido. Esperaba acompañar mis disculpas con una explicación educada: era la última vez, porque teníamos previsto estar en el salón parroquial la semana siguiente. Los niños ni siquiera se dieron cuenta y continuaron el juego. Al fin y al cabo, quizá no fuera nadie. Era un día ventoso y en el edificio había corrientes de aire. Tal vez la puerta no se había cerrado bien y el viento la había abierto un momento antes de cerrarla de golpe. Seguí mirándola, pero como no pasaba nada, volví a centrar mi atención en los niños.

Unos instantes después, volvió a abrirse una rendija. Y esta vez vislumbré a un mirón. Pero mientras miraba, la puerta se cerró de golpe. Era hora de investigar. Cuando los niños vieron que me ponía de pie, el juego se detuvo. Con un gesto les insté a continuar y fui a ver qué ocurría. «¿Hay alguien ahí?», dije abriendo la puerta de par en par.

En el pasillo poco iluminado había una adolescente encorvada, de cara ovalada y pelo largo, despeinado y rubio. Llevaba un uniforme escolar genérico: blusa blanca, rebeca negra y pantalones negros, pero sin corbata, por lo que era imposible saber a qué colegio asistía.

«¿Eres Torey?», preguntó.

«Sí».

«La señora Thomas dijo que me ayudaría».

Arqueé las cejas, desconcertado. Hacía semanas que no hablaba con Meleri y mi asociación no me había alertado de una nueva llegada. La sesión de ese día era el único trabajo que estaba haciendo para los servicios sociales en ese momento. El llamado «grupo de enriquecimiento» era para niños con necesidades especiales de hasta ocho años, procedentes de entornos desfavorecidos. Nos reuníamos una hora a la semana para trabajar las habilidades interpersonales. Nadie me había hablado de un adolescente.

«¿Cómo te llamas?», pregunté.

«Eloise».

«¿Eloise qué?»

Se quedó callada un momento, agarrándose los hombros imperceptiblemente, como si tuviera que pensárselo, y luego contestó: «Eloise Jones».

Ese momento de vacilación me hizo pensar que se resistía a decir su apellido. Quizá se lo había inventado, pero aunque fuera cierto, no podía deducir gran cosa, dado que un tercio de los habitantes de esa región de Gales se llaman Jones.

«Debe de haber habido un malentendido, porque no estás en mi programa».

«La señora Thomas dijo que me ayudaría», repitió.

Miré el reloj. «Con este grupo termino a las cuatro y media. Después estoy libre».

Su expresión era indescifrable. Había una especie de distanciamiento, que me hizo sentir como si le hubiera hecho preguntas sin sentido.

«Tengo que volver ahora», dije, sin necesidad de imaginar el caos que encontraría, porque podía oírlo. Abrí la puerta de par en par para que los niños supieran que estaba allí.

«¿Puedo esperar?», preguntó Eloise.

«Faltan al menos veinte minutos».

«No importa».

No había razón para dejarla en el pasillo. Estábamos jugando en grupo, así que accedí. «De acuerdo», y volví a entrar en la habitación, seguido por Eloise.

«¿Quién es?», preguntó uno de los niños.

«Sí, ¿quién es?», exclamó otro desde el lado opuesto.

«Es una invitada. Se llama Eloise. ¿Cómo se saluda a un invitado, Dylan? ¿Gritas 'Quién eres' o dices...?».

«¡Ya lo sé! ¡Ya lo sé! ¡Lo sé! Señora, ¡lo sé!» Era Sallie, de ocho años, que ni siquiera desdeñó abrirse paso entre las sillas para llegar hasta nosotras. «¿Cómo estás?», le dijo a Eloise. «Hola, ¿qué tiempo hace?». Los modales de Sallie habrían sido un poco más convincentes si no llevara la palabra «asco» pegada a la frente.

Había una fila de sillas alineadas a lo largo de la pared lateral e imaginé que Eloise elegiría una de ellas para esperar a que yo terminara con el grupo. Pero me siguió y se sentó con nosotros en nuestro círculo.

Los niños parecían hechizados. Casi todos demasiado tímidos para hablarle, bailaban de un lado a otro, sin ningún deseo de reanudar el Juego de los Tontos. Sólo Dylan, un robusto niño de siete años con el físico de un jugador de rugby en miniatura, no tuvo tales vacilaciones. «¿Quiénes sois? ¿Por qué estás aquí?»

Anuncié: «Esta es Eloise. Ha venido a vernos hoy».

«¿Pero por qué?»

Responder a esa pregunta no era nada fácil, porque yo tampoco lo sabía. «Ha venido a vernos, Dylan. Eso debería ser suficiente información para ti».

«¿De dónde eres?», le preguntó.

«Por favor, Dylan, siéntate», le insté.

«¿Eres galés?», insistió.

«Dylan...»

«¿T' siarad Cymraeg?»

«Dylan...»

«Me gustaría saber si formarás parte de este grupo. ¿Serás parte de este grupo? Porque eres demasiado grande para estar en este grupo. Y ya hay suficientes chicas».

«Stedd i lawr.» Me levanté para asegurarme de que obedecía y fui a sentarme. Dio un paso atrás y volvió a su asiento, pero siguió mirando a Eloise con desconfianza.

Al darme cuenta de que no recuperaríamos la concentración necesaria para el juego, decidí terminar con un cuento. Opté por Un tigre a la hora del té, de Judith Kerr, por su intrigante argumento, protagonizado por una niña y un tigre de aspecto femenino que aparece de la nada en su casa. También lo elegí por las principales emociones que despierta: emoción y ansiedad en particular. ¿Quién no se sentiría emocionado ante la idea de acoger a un tigre de verdad en su casa? ¿Quién no sentiría ansiedad?

Leí la historia y, para concluir, comenté: «Era un tigre muy hambriento, ¿verdad? ¿Qué fue lo primero que comió?».

«Gente», respondió Carly. «Los tigres comen gente».

«Pero el tigre de esta historia no se comió a nadie. ¿Qué comía?»

«Los tigres comen gente», insistió Carly.

«Le compraron comida para tigres», intervino Owen.

«Al final, decidieron que comprarían una lata de comida para tigres por si ella volvía a verlos», respondí. «Pero cuando llegó a la hora del té, no le dieron comida para tigres. ¿Qué le dieron en su lugar?

Dylan resopló: «La comida para tigres no existe. No puedes ir a una tienda y comprar una lata de comida para tigres».

«¿Qué le dieron?», volví a preguntar.

«¡Todo!», exclamó Sallie. «Todo lo que tenían para merendar. Y además se lo bebía todo. Todo su té y su zumo de naranja y toda su agua también».

«Gracias», dije, aliviada de que alguien al menos me hubiera escuchado.

«No creo que sea posible beberse toda el agua del grifo», intervino Eloise.

Sorprendida, la examiné con la mirada.

El grifo está conectado a las tuberías de agua. Para vaciar el grifo, el tigre tendría que beberse un acueducto entero. Esto no es creíble.

Los niños estaban tan sorprendidos como yo de que Eloísa se hubiera unido a la conversación. Sobre todo, creo, porque nunca se les había ocurrido cuánta agua podría haber, exactamente, en el grifo de su cocina.

Yo, en cambio, no esperaba que participara, entre otras cosas porque se trataba de una historia fantástica sobre un tigre que se sienta a tomar el té con una niña y su madre, y no de un documental sobre la naturaleza.

«Y ni una sola vez pidió ir al baño», añadió Sallie.

Finalmente, cuando los niños se marcharon, me volví hacia Eloise, que se había quedado en su silla del círculo. Me senté a su lado. «Dime qué puedo hacer por ti».

«Necesito volver con mi familia de acogida, en Moelfre».

Desconcertada por la petición, observé: «Está lejos de aquí». Como yo no hacía nada ni siquiera vagamente relacionado con transportar niños de un lado a otro, pregunté: «¿Podrías explicarme un poco más?».

Eloise apartó la mirada y apenas resopló, con aspecto un poco frustrado, como hacen los adolescentes cuando los adultos resultan ser obtusos. Luego volvió a resoplar, como si recapacitara. «Hubo un gran malentendido. Sobre el anillo. No lo había cogido. En serio, no lo había cogido, pero Olivia se había enfadado, así que me obligaron a dejar a los Powell para ir a ese otro sitio, que odio. Pero sólo fue un malentendido.

Olivia me mandó un mensaje para decirme que lo sentía. Verás, ese chico, Sam, me lo había dado. El anillo, quiero decir. Pero pertenecía a Olivia, y él lo había cogido, y ahora se ha dado cuenta de que no era yo. Por eso tengo que devolvérselo, si no, me meteré en un buen lío».

Estaba perdido. No sabía absolutamente nada de esta obra ni de sus personajes. «Demos un paso atrás. ¿Te dijo la señora Thomas que yo te ayudaría?».

Eloise asintió. «Ella dijo que usted escribe libros. Y que ayuda a la gente».

«¿Te explicó también cómo podría ayudarte?».

Eloise asintió. «Dijo que escribes libros. Y que ayudas a la gente».

«¿Te explicó también cómo podía ayudarte?».

Otro suspiro de frustración, esta vez más impaciente. «A mí no. Lo dijo la señora Thomas. Le expliqué que tenía que devolver el anillo a Olivia, y la señora Thomas afirmó que podía ayudarme porque escribe libros. Así que, por favor. Para eso he venido. Por favor».

No entendí nada de esa historia. ¿Una perfecta desconocida acude a mí y quiere que la ayude a volver con su antigua familia de acogida para devolver una joya? Era como una extraña versión de El Señor de los Anillos al estilo de los servicios comunitarios.

«¿A qué colegio vas?», le pregunté.

«Esto no tiene nada que ver con el colegio», respondió Eloise.

La miré.

Cuando se dio cuenta de que no iba a continuar la conversación hasta que me contestara, dijo: «Ysgol Dafydd Morgan» con un suspiro irritado. Yo sabía que era un instituto de secundaria en una ciudad costera a unos quince kilómetros.

«No se podía llegar tan rápido desde Dafydd Morgan».

Eloise agrandó los ojos para expresar lo irritante que le resultaba. «Cogí el autobús».

«¿Te largaste?», insistí.

Ella negó con la cabeza. «No».

«¿Te han dado permiso para irte antes?», pregunté escéptico.

Su voz se volvió patética. «Por favor. Por favor».

Hice una pausa para pensar y el silencio nos envolvió.

Cuando levanté la cabeza, Eloise había bajado los ojos, dándome tiempo para estudiarla. Su aspecto no tenía nada de especial. Rasgos insignificantes, ojos mundanos de color azul grisáceo, boca pequeña, labios finos. Pelo castaño claro, largo y ondulado, que probablemente llevaba recogido en clase, suelto sobre los hombros. Me la imaginaba como uno de esos niños que se escapan del colegio sin ser vistos, y viven al margen de la vida pasando siempre desapercibidos.

«¿Me enseñas el anillo?», le pregunté, sobre todo para comprobar que realmente estaba ahí.

Colocó sobre su regazo la pequeña bolsa negra que llevaba al hombro y la abrió. Al principio rebuscó en ella inútilmente, lo que me hizo sospechar de inmediato que no me había dicho la verdad.

Como si percibiera mi incredulidad, Eloísa parecía visiblemente angustiada mientras abría más la bolsa y empezaba a buscar de nuevo.

«Un momento», le dije, “¿de dónde has sacado todas estas medicinas?”. Entre el contenido de la bolsa vislumbré varios paquetes de paracetamol.

Sin responder, rápidamente empujó las cajas al fondo de la bolsa, ocultándolas con otras cosas.

«No, espere. Déjame ver, por favor», le insistí, tendiéndole una mano. Eloísa se resistió, apretando la bolsa contra su cuerpo.

«Dame tu bolso, por favor».

«Es mío.

«Sí, lo sé, pero por favor, dámelo».

Durante un largo momento sostuvo la bolsa con fuerza contra su pecho. Nuestros ojos se encontraron.

«Por favor, dámelo», repetí.

Finalmente, con un suspiro, me la entregó.

Coloqué la bolsa sobre mi regazo y la abrí. Una, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco cajas de paracetamol, dieciséis comprimidos cada una. Uno podía comprar un máximo de dos cajas -treinta y dos comprimidos en total- para reducir la probabilidad de muerte en caso de sobredosis. Comprar cinco cajas significaba tener un plan definido en mente, y para mí eso sólo significaba una cosa: el suicidio.

«¿Qué es todo esto?», pregunté.

«Sólo son pastillas para el dolor de cabeza».

«Son demasiadas para un dolor de cabeza».

«Sufro de migrañas».

«Son demasiadas incluso para una migraña».

La desesperación se pintó en su rostro. «No es lo que parece», dijo.

«Son demasiados medicamentos para tomarlos todos a la vez».

Las comisuras de sus labios se doblaron hacia abajo. Le temblaba la barbilla.

«Ha ocurrido algo grave, ¿verdad?».

Asintió con la cabeza.

«¿Quieres contármelo?

Negó con la cabeza.

«Te ayudaré con mucho gusto, si puedo, pero necesito saber qué está pasando».

Eloise volvió a negar con la cabeza.

«¿Qué puedo hacer para ayudarte?», pregunté.

«Por favor, acompáñame a Moelfre».

«No puedo hacerlo. Te llevaré al colegio si quieres. O al despacho de la señora Thomas».

«No, me gustaría ir a casa».

«No lo entiendo», objeté. «Moelfre está definitivamente más arriba, y tú asistes a Ysgol Dafydd Morgan, que está a unos treinta kilómetros en dirección opuesta. Así que no creo que tu casa esté en Moelfre».

«Sí que lo está. Y necesito que me acompañes hasta allí».

«Déjeme telefonear a la Sra. Thomas para entenderlo mejor. Mientras tanto, dejemos esto aquí», dije, cogiendo las cajas de paracetamol.

«¿Pero no lo entiendes?», gimió Eloise. «Tengo que volver con Olivia. Tengo que llevarle el anillo». Agitó las manos frenéticamente, casi como si quisiera golpearse, pero no lo hizo. Cruzando los brazos firmemente contra el pecho, arponeó los hombros, balanceándose hacia delante.

Sentí una punzada de miedo. No sabía nada de aquella niña, pero intuía la autodestrucción en su comportamiento y problemas mucho mayores que tener que devolver un anillo a alguien.

Source image / Fuente imagen: Torey Hayden.

Mis Blogs y Sitios Web / My Blogs & Websites: