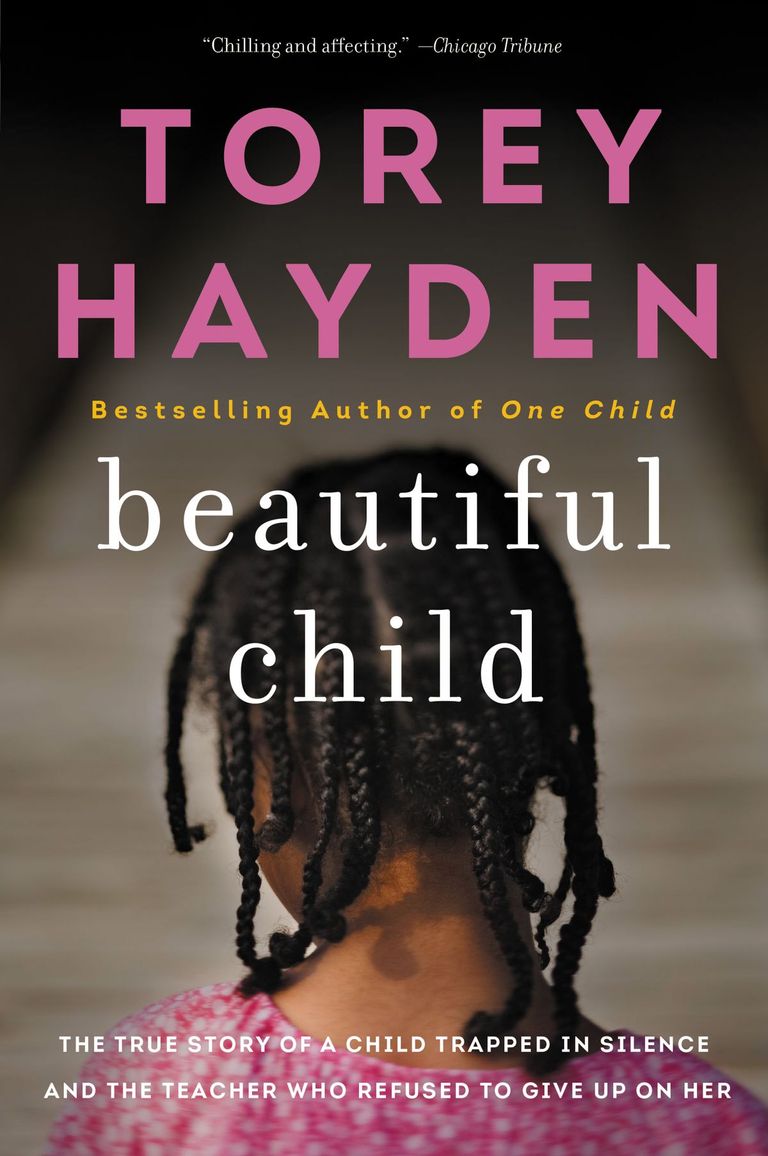

Torey Hayden, author of this autobiographical novel, has been involved for years in the education of children with disabilities or severe socioeconomic hardship, when in the United States there was still the organization of special schools or classes for students in need of special attention. The affection, esteem and care for the children that the author was in charge of shine through in the pages... the harsh, almost unreal situations of violence and abuse towards the children are presented, but also their capacity for resilience, recovery and self-improvement.

Torey Hayden, autora de esta novela autobiográfica, se implica desde hace años en la educación de niños en situación de discapacidad o de graves penurias socioeconómicas, cuando en Estados Unidos todavía existía la organización de escuelas o clases especiales para estudiantes que necesita atención especial. El cariño, la estima y el cuidado por los niños que la autora tuvo a su cargo brillan en las páginas... se presentan situaciones durísimas, casi irreales, de violencia y maltrato hacia los niños, pero también su capacidad de resiliencia, recuperación y superación personal.

Venus is seven years old and spends her school hours in an apparently catatonic state: she does not speak, does not listen, does not react to stimuli except when she suffers violent attacks of rage against everything and everyone, transforming herself into a “terrible little death machine”. Step by step, Torey Hayden manages to gain the little girl's trust, creating special channels of communication with her and demonstrating how tenacity, strength and love are the best tools for interacting with difficult children. Thanks to Torey's help, Venus will thus find partial redemption and the possibility of a normal life.

Venus tiene siete años y pasa sus horas de escuela en un estado aparentemente catatónico: no habla, no escucha, no reacciona a los estímulos excepto cuando sufre violentos ataques de ira contra todo y todos, transformándose en una "pequeña y terrible máquina de muerte". Paso a paso, Torey Hayden logra ganarse la confianza de la pequeña, creando canales de comunicación especiales con ella y demostrando cómo la tenacidad, la fortaleza y el amor son las mejores herramientas para interactuar con niños difíciles. Gracias a la ayuda de Torey, Venus encontrará así una redención parcial y la posibilidad de una vida normal.

The first time I saw her she was on top of the small wall that ran along the west side of the courtyard.

She was lying on her stomach, one leg stretched out and the other bent, her thick black hair falling down behind her back, her eyes closed and her face turned toward the sun.

Her black hair fell behind her back, her eyes closed and her face turned towards the sun. The pose gave her the air of a glamorous Hollywood queen of yesteryear, and it was this that attracted my attention.

I was not surprised because that little girl couldn't have been more than six or seven years old.

I walked past her and down the path that led to the school. The principal, Bob Christianson, saw me coming and came out of his office. “How nice!” he shouted cheerfully, tapping me on the shoulder.

“I'm so glad to see you.

What a beauty. I've been looking forward to it. We're going to have fun this year, eh? Ah, yes we are going to have fun.” In all the excitement, I could only laugh. Bob and I had known each other for a long time. When I was young and inexperienced, he had offered me one of my first jobs.

At the time, he was running a research program on learning disabilities and his exuberant, carefree and somewhat hippy approach to the disadvantaged and difficult children in his care had caused quite a stir in the then rather conservative environment. I must admit that it alarmed me a little, because I had just finished my internship and was not used to always thinking for myself.

Bob, refusing to believe the things I claimed to have learned in college, had given me just the right amount of guidance and encouragement. So, for two overwhelming, crazy years, I would say, I learned in the classroom, day after day, to stand on my own two feet and find my own style.

The work environment at that time was almost ideal for me, and it was Bob - practically only Bob, practically only him, who turned me into the teacher I would later become. The thing is, in the end, I had succeeded all too well. Not only had I learned to question the precepts and practice of the theories I had learned in college: I had begun to question Bob's as well. His approach was based on a folk psychology too flimsy to satisfy me. So when I realized that I could no longer grow in that environment, I left.

Some time had passed since then, for both of us. I had worked in other schools, in other states, even in other countries. I had expanded my activities to clinical psychology and research, while continuing to work in special courses. And for a couple of years I hadn't even taught.

Bob, for his part, had remained in the same city, moving from the public sector to the private sector, from special courses to regular courses.

We only spoke occasionally and neither of us knew exactly what the other was doing.

What the other was doing. So it was a pleasant surprise to learn that Bob was now the principal of the school to which I had been assigned.

Our state's school system was in the midst of one of its never-ending reorganization processes. The previous year I had worked in a neighboring school district as an intern support teacher.

As a practicum support teacher I went from school to school to work with small groups of children and to assist teachers who had special students integrated into their classes. Although this program had only been in place for two years, the authorities had come to the conclusion that for the most severe children, the results were not good enough. Thus, one-third of the support teachers had been assigned to provide the children with the most severe and aggressive behavior with special time classes.

I had rejoiced at the prospect of giving up my vagabond life and having a class of my own.

“And wait till you see your class,” Bob was saying as we climbed the stairs. And more stairs.

“It's a beautiful classroom, Torey. As soon as I heard you were coming, I looked for a place where I could really work. They usually give special classes what they can spare.

But therein lies the beauty of this beautiful old building.”

And in the meantime we climbed another flight of stairs. “That there's room to spare.” Bob's school was a hybrid construction: a 1910 brick prominence to which a prefabricated portion had been added in the 1960s.

In the 1960s they had added a prefabricated portion to accommodate the baby boom. I had been assigned a classroom on the top floor of the old wing, and Bob hadn't exaggerated: it was a beautiful, spacious, lovely, airy one, with large windows, freshly painted bright yellow walls, and an alcove where you could put your coats and all the kids' stuff. It was probably the nicest classroom I had ever had.

The drawback was that, separating me from the bathroom, there were three flights of stairs and a corridor. Not to mention the gym, the canteen and the secretary's office, which were even in another galaxy.

“You can make whatever changes you want,” Bob was saying, and all the while walking between tables and seats. “And Julie is coming this afternoon. Have you two met? She'll be your assistant.

What's the politically correct term, paralegal?

No, no... For educator? I don't remember anymore. Anyway, she's only going to do half a day with you.

Unfortunately. I couldn't find anything better. But you'll see, you'll like Julie. She's been here for three three years. In the morning she comes to support a child with cerebral palsy. But in the afternoon the little guy has psychotherapy sessions - Julie loads him on the school bus and then she's all yours.”

As Bob spoke, I wandered around the classroom looking here and there. I stopped in front of the window to assess the view.

The little girl was still on the small wall, sitting. I looked at her.

She looked sad and lonely. On that last day of summer vacation, there were no other children around.

Bob said, “Your registration will be ready this afternoon.

We have assigned you five children full time. Plus you'll have about fifteen who will come in and out as needed. How does that sound? Are you happy?” I smiled and nodded.

“Pleased.” I was trying to move a file cabinet out of the way-

“Wait, I'll give you a hand,” Julie said cheerfully, and grabbed the other end of the file cabinet. We pushed it into a corner.

“Bob told me you were slaving away up here-are you all right?”

“Yes, thank you,” I replied.

She was a pretty girl. Not really a girl, actually: she certainly looked less than her age. But she was petite, with a delicate build, a fair, fresh complexion and light green eyes.

And she had straight reddish-blonde hair, with thick bangs otherwise cut short behind her ears, which gave her a sweet schoolgirl air. She didn't look a day over fourteen.

“I can't wait to get started,” she said, wiping dust from her hands. “I've been rooting for Casey Muldrow since he's been in first grade. And he's a great kid, but I was looking forward to doing something different.”

“If you were looking for something 'different,' you're probably in luck,” I said with a smile.

“I'm a specialist in the field.” I took a scallop in my hand and unrolled it whole. “I was thinking of putting it up there, between the windows, can you give me a hand?”. That's when I saw the little girl again. She was still on the same little wall, but this time there was a woman talking to her underneath.

“That little girl must have been up there for four hours,” I said, ”She was already there this morning when I arrived.”

Julie looked out the window. “Ah, yes. That's Venus Fox. And that's her little wall. She's always there.”

“Why?” Julie shrugged. “Because that's Venus' little wall.”

“And how does she get up there? She must be three feet high that little wall.”

“That little girl is like Spiderman. She can climb anywhere.”

“Is that the mother with her?”

“No, that's the sister. Wanda. She's mentally retarded.”

“She looks a little old to be her sister.” Julie shrugged again. “She's a little under twenty.

Or maybe twenty. In high school she was in the special classes, but then she got too old. Now she apparently spends her time running after Venus.”

“And Venus spends most of her time on a little wall. Promising family, huh?” Julie looked up her eyes to the sky with an air of knowing a lot. “That's nine. Nine children. Almost all from different fathers.

And I think they've all been in a special class at one time or another.”

“Even Venus?”

“Venus definitely. She's crazy as a loon.” And he made a mischievous little resolution. “You'll find out soon enough. She'll come to this class.”

“Mad as a loon in what way?”, I asked.

“For one thing, he doesn't talk.” Here I raised my eyes to heaven. “What a surprise!” And, as Julie looked at me questioningly, I explained, “I specialize precisely in elective mutism.

Elective mutism. In fact, I started treating it right around the time Bob and I worked together on another program.”

“Ah. Yes, but that child is really mute.”

“She'll stop being mute here.”

“No, you don't understand,” he replied. “Venus doesn't talk. She doesn't speak. She doesn't say a single word.

From nowhere. To no one.”

“In here she will.” Julie's smile was serene, but a mocking thread. “Pride comes before ruin.”

La primera vez que la vi estaba en lo alto del pequeño muro que recorría el lado oeste del patio.

Estaba tumbada boca abajo, con una pierna estirada y la otra doblada, el pelo negro y espeso le caía por detrás de la espalda, los ojos cerrados y la cara vuelta hacia el sol.

El pelo negro le caía por detrás de la espalda, los ojos cerrados y la cara vuelta hacia el sol. La pose le daba La pose le daba el aire de una glamurosa reina de Hollywood de antaño, y fue esto lo que atrajo mi atención.

Porque aquella niña no tendría más de seis o siete años.

Pasé junto a ella y bajé por el camino que llevaba a la escuela. El director, Bob Christianson, me vio llegar y salió de su despacho. «¡Qué bien!», gritó alegremente, dándome un golpecito en el hombro.

«Me alegro tanto de verte.

Qué belleza. Lo estaba deseando. Nos vamos a divertir este año, ¿eh? Ah, sí que nos vamos a divertir». En tanto entusiasmo, sólo pude reírme. Bob y yo nos conocíamos desde hacía tiempo. Cuando yo era joven e inexperta, me había ofrecido uno de mis primeros trabajos.

Por aquel entonces, dirigía un programa de investigación sobre problemas de aprendizaje y su enfoque exuberante, despreocupado y un tanto hippy con los niños desfavorecidos y difíciles a su cargo había había causado un gran revuelo en el entorno, entonces bastante conservador. Debo admitir que a mí alarmado un poco, porque acababa de terminar mis prácticas y no estaba acostumbrado a pensar siempre por mí mismo.

Bob, negándose a creer las cosas que yo decía haber aprendido en la universidad, me había dado la cantidad justa de orientación y aliento. Así, durante dos años abrumadora, loca, diría yo, aprendí en el aula, día tras día, a valerme por mí misma y a encontrar mi propio estilo.

El ambiente de trabajo en aquella época era casi ideal para mí, y fue Bob -prácticamente solo Bob, prácticamente solo él, quien me convirtió en el profesor que luego sería. El caso es que, al final, lo había conseguido demasiado bien. No sólo había aprendido a cuestionar los preceptos y la práctica de las teorías aprendidas en la universidad: también había empezado a cuestionar las de Bob. El su enfoque se basaba en una psicología popular demasiado endeble para satisfacerme. Así que cuando me di cuenta de que no podía seguir creciendo en aquel entorno, me marché.

Había pasado algún tiempo desde entonces, para ambos. Había trabajado en otras escuelas, en otros estados, incluso en otros países. Había ampliado mis actividades a la psicología clínica y a la investigación, mientras continuaba trabajando en cursos especiales. Y durante un par de años ni siquiera había dado clases.

Bob, por su parte, había permanecido en la misma ciudad, pasando del sector público al privado, de los cursos de los cursos especiales a los regulares.

Sólo hablábamos de vez en cuando y ninguno de los dos sabía exactamente qué hacía el otro.

Así que fue una agradable sorpresa enterarme de que Bob era ahora el director de la escuela a la que me habían asignado.

El sistema escolar de nuestro estado estaba en medio de uno de sus interminables procesos de reorganización. El año anterior había trabajado en un distrito escolar vecino como profesor de apoyo en prácticas.

Como profesor de apoyo en prácticas iba de un colegio a otro para trabajar con pequeños grupos de niños y para ayudar a los profesores que tenían alumnos especiales integrados en sus clases. Aunque ese programa sólo se había puesto en marcha dos años antes, las autoridades habían llegado a la conclusión de que para los niños más graves los niños más graves, los resultados no eran suficientemente buenos. Así, un tercio de los profesores de apoyo habían sido asignados para ofrecer a los niños con comportamiento más grave y agresivo clases a tiempo especial.

Me había alegrado ante la posibilidad de abandonar mi vida de vagabundo y tener una clase propia.

«Y espera a ver tu clase», decía Bob mientras subíamos las escaleras. Y más escaleras.

«Es un aula preciosa, Torey. En cuanto supe que venías, busqué un lugar donde pudiera trabajar de verdad. Normalmente dan a las clases especiales lo que les sobra.

Pero ahí radica la belleza de este hermoso edificio antiguo».

Y mientras tanto subimos otro tramo de escaleras. «Que hay sitio de sobra». La escuela de Bob era una construcción híbrida: una prominencia de ladrillo de 1910 a la que se había añadido una parte prefabricada en los años sesenta.

En los sesenta habían añadido una parte prefabricada para dar cabida al baby boom. Me habían asignado un aula en el último piso del ala antigua, y Bob no había exagerado: era una hermosa, espaciosa preciosa, espaciosa, con grandes ventanales, paredes amarillas brillantes recién pintadas y un nicho donde se podían poner los abrigos y todas las cosas de los niños. Probablemente era la clase más bonita que había tenido nunca.

El inconveniente era que, separándome del cuarto de baño, había tres pisos de escaleras y un pasillo. Por no hablar del gimnasio, la cantina y la secretaría, que estaban incluso en otra galaxia.

«Puedes hacer los cambios que quieras», decía Bob, y mientras tanto caminaba entre mesas y asientos. «Y Julie viene esta tarde. ¿Ya os conocéis? Será tu ayudante.

¿Cuál es el término políticamente correcto? ¿Paralegal?

No, no... ¿Paraeducadora? Ya no me acuerdo. De todos modos, ella sólo va a hacer la mitad de un día con usted.

Desgraciadamente. No pude encontrar nada mejor. Pero ya verás, te gustará Julie. Ella ha estado aquí por tres tres años. Por la mañana viene a apoyar a un niño con parálisis cerebral. Pero por la tarde el pequeño tiene sesiones de psicoterapia: Julie lo carga en el autobús escolar y luego es toda tuya».

Mientras Bob hablaba, yo paseaba por el aula mirando aquí y allá. Me detuve frente a la ventana para evaluar la vista.

La niña seguía en el pequeño muro, sentada. La miré.

Parecía triste y sola. En aquel último día de las vacaciones de verano, no había otros niños alrededor.

Bob dijo: «Su registro estará listo esta tarde.

Te hemos asignado cinco niños a tiempo completo. Además tendrás unos quince que que entrarán y saldrán cuando sea necesario. ¿Qué le parece? ¿Estás contenta?». Sonreí y asentí.

«Encantada». Intentaba apartar un archivador para que no estorbara-

«Espera, te echo una mano», dijo alegremente Julie , y agarró el otro extremo del archivador. Nosotras lo empujamos hacia un rincón.

«Bob me dijo que estabas trabajando como una esclava aquí arriba. ¿Estás bien?»

«Sí, gracias», respondí.

Era una chica guapa. No realmente una chica, en realidad: ella ciertamente parecía menos de su su edad. Pero era menuda, de complexión delicada, tez clara y fresca y ojos verdes claros.

Y tenía el pelo rubio rojizo liso, con flequillo grueso y por lo demás cortado detrás de las orejas, lo que le daba un dulce aire de colegiala. No parecía tener más de catorce años.

«Estoy impaciente por empezar», dijo, limpiándose el polvo de las manos. «He estado apoyando a Casey Muldrow desde que está en primer grado. Y es un gran chico, pero tenía ganas de hacer algo diferente».

«Si estabas buscando algo 'diferente', probablemente estás de suerte», dije con una sonrisa.

«Soy un especialista en la materia». Cogí un festón con la mano y lo desenrollé entero. «Estaba pensando en ponerlo ahí arriba, entre las ventanas. ¿Me echas una mano?». Fue entonces cuando volví a ver a la niña. Seguía en el mismo pequeño muro, pero esta vez había una mujer hablándole debajo.

«Esa niña debe de llevar cuatro horas ahí arriba», dije. «Ya estaba allí esta mañana cuando llegué».

Julie miró por la ventana. «Ah, sí. Esa es Venus Fox. Y esa es su pequeña pared. Ella siempre está allí.»

«¿Por qué?» Julie se encogió de hombros. «Porque ese es el pequeño muro de Venus».

«¿Y cómo se sube ahí? Debe tener un metro de alto ese pequeño muro».

«Esa niña es como Spiderman. Puede trepar por cualquier sitio».

«¿Es la madre la que está con ella?»

«No, esa es la hermana. Wanda. Es retrasada mental».

«Parece un poco mayor para ser su hermana». Julie se encogió de hombros de nuevo. «Ella es un poco menos de veinte.

O quizá veinte. En el instituto estaba en las clases especiales, pero luego se hizo demasiado mayor. Ahora aparentemente pasa su tiempo corriendo detrás de Venus».

«Y Venus pasa la mayor parte del tiempo en un pequeño muro. Una familia prometedora, ¿eh?» Julie miró hacia arriba sus ojos al cielo con aire de saber mucho. «Son nueve. Nueve hijos. Casi todos de distinto padre.

Y creo que todos han estado en una clase especial en algún momento».

«¿Incluso Venus?»

«Venus definitivamente. Está loca como una cabra». Y tomó una pequeña resolución maliciosa. «Te darás cuenta pronto. Vendrá a esta clase».

«¿Loca como una cabra en qué sentido?», pregunté.

«Para empezar, no habla». Aquí levanté los ojos al cielo. «¡Qué sorpresa!» E, mientras Julie me miraba interrogante, le expliqué: «Estoy especializado precisamente en mutismo electivo.

Mutismo electivo. De hecho, empecé a tratarlo justo cuando Bob y yo trabajamos juntos en otro programa».

«Ah. Sí, pero esa niña es realmente muda».

«Dejará de ser muda aquí».

«No, no lo entiendes», replicó. «Venus no habla. No habla. No dice ni una sola palabra.

Desde ninguna parte. A nadie».

«Aquí dentro lo hará». La sonrisa de Julie era serena, pero un hilo burlona. «El orgullo va antes que la ruina.»

Source image / Fuente imagen: Torey Hayden.