Antes de la pandemia del Covid volví a Berlín tratando de reencontrarme con nuevas sensaciones, viejos amigos y una ciudad muy particular.

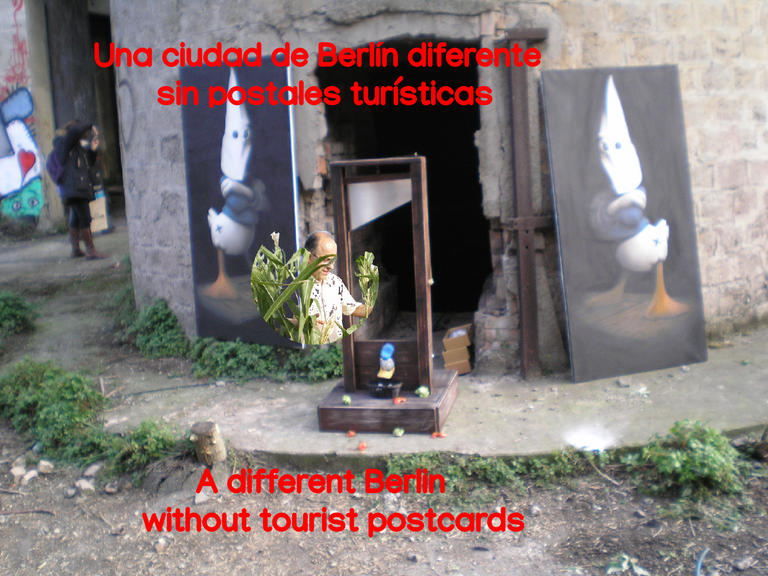

Hoy quiero mostrarles el lado común, "normal", lejano de las postales turísticas que esta ciudad, que muchos consideran el verdadero motor económico de Europa.

He vuelto a Berlín, cuatro años después -antes de que la epidemia de coronavirus se extendiera por todo el mundo-, cuando dejé una ciudad gris en un otoño frío, la encuentro abrasada por un sol abrasador que evapora sus humos malolientes.

Quiero recorrerla de nuevo, no la ruta turística de la Puerta de Brandeburgo, el Reichstag, el edificio de comunicaciones, todo para uso y consumo de los turistas, sino la otra, la de los barrios pobres, la periferia de Berlín.

En la estación de Ostbanhof, antiguo Berlín Este, me encuentro con unas personas al borde de la carretera, tumbadas en un viejo platillo desgastado, utilizando una jeringuilla para extraer su dosis, ante la mirada indiferente de los transeúntes. Apenas ha pasado el mediodía.

Son imágenes despiadadas y tristes de un Berlín que no olvida las miserias de hace muchos años, no sólo porque es el que me acogió, sino porque Berlín me ha vuelto a dejar esa sensación de náusea y desasosiego que me produjo la primera vez. Berlín, manchada con la sangre del Holocausto, es la ciudad que no olvida.

Pero también es el Berlín que hace penitencia, se arrodilla ante el visitante y abre su archivo de recuerdos que otros lugares mantendrían en secreto. Te enfrenta a ellos, sin piedad, sin edulcorantes. Y eso también es positivo más allá de las postales turísticas.

Before the Covid pandemic, I went back to Berlin trying to rediscover new sensations, old friends and a very particular city.

Today I want to show you the common, "normal" side, far from the tourist postcards that this city, which many consider the real economic engine of Europe, has to offer.

I have returned to Berlin, four years later - before the coronavirus epidemic spread around the world - when I left a gray city in a cold autumn, I find it scorched by a blazing sun that evaporates its foul-smelling fumes.

I want to walk it again, not the tourist route of the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, the communications building, all for the use and consumption of tourists, but the other one, the one of the poor neighborhoods, the periphery of Berlin.

At the Ostbanhof station, former East Berlin, I meet some people on the side of the road, lying on an old worn-out saucer, using a syringe to extract their dose, under the indifferent gaze of passers-by. It is barely past noon.

They are merciless and sad images of a Berlin that does not forget the miseries of many years ago, not only because it is the one that welcomed me, but also because Berlin has left me again with that feeling of nausea and uneasiness that it gave me the first time. Berlin, stained with the blood of the Holocaust, is the city that does not forget.

But it is also the Berlin that does penance, kneels before the visitor and opens its archive of memories that other places would keep secret. It confronts you with them, without mercy, without sweeteners. And that is also positive beyond the tourist postcards.