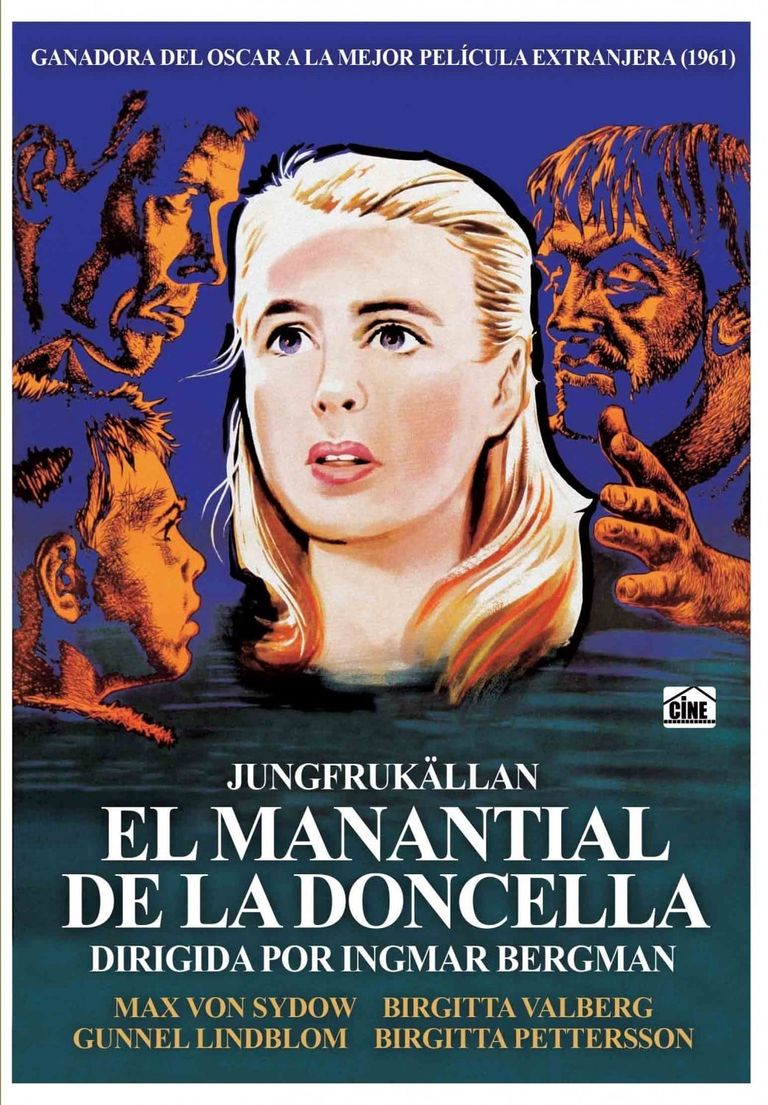

En plena madurez artística, cuando ya tenía 20 películas como director sobre sus espaldas Ingmar Bergman dirige una de sus obras más emblemáticas e icónicas (no solo en el sentido religioso) de toda su carrera, El Manantial de la Doncella basada en una leyenda sueca del siglo XIV.

No sólo por los premios ganados (el Premio Especial del Jurado del Festival de Cannes en 1960 serviría de preludio al Oscar de la Academia de Hollywood a la mejor película extranjera y al Globo de Oro por el mismo concepto al año siguiente (1961), sino porque es la única película dirigida por Bergman en la cuál el tema religioso -siempre presente en su obras- termina coincidiendo en sus aspectos humano y divino.

En la Suecia medieval del siglo XIV la tradición prevé que una doncella virgen le deposite velas a la Virgen María en un día de fiesta.

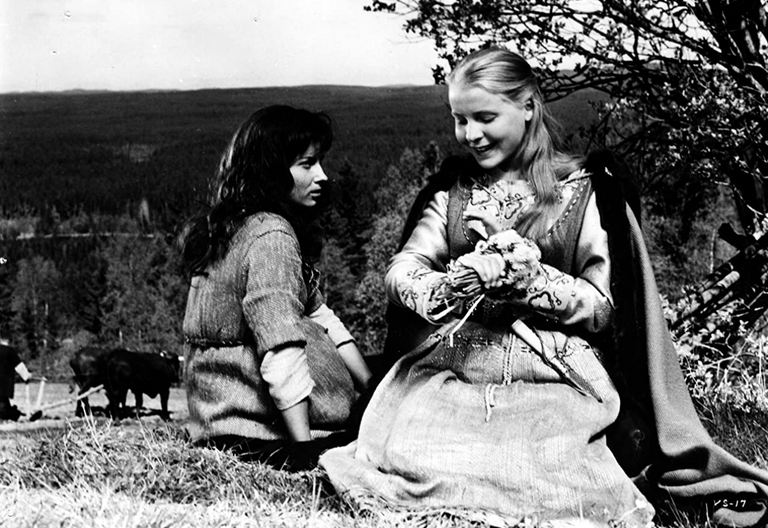

El rico terrateniente Töre (estupenda actuación de Max von Sydow) que cree en el Dios cristiano, pero que utiliza un ritual pagano (agua hirviendo y ramas de árbol realizado antes del desenlace final) encarga a su hija Karin, bella, candida e inocente, de cumplir con tal misión, acompañada por Ingeri una joven deshonrada -ha quedado embarazada después de haber sufrido violencia carnal- y pagana (pasa sus días adorando al dios Odín).

Durante el viaje dos pastores acompañados por un chico ven pasar la copia, las acechan y finalmente las atacan, violando y matando a la joven Karin -el chico no participa- mientras Ingeri huye. En realidad ni siquiera intenta ayudarla con su conciencia y su fuerza de voluntad carcomidas por la envidia hacia la joven.

En su huída los pastores se hacen pasar por pastores extraviados y buscan refugio -sin saberlo- en la casa del padre de Karin.

Luego de haber comida y descansado los malhechores tratan de pagar la amabilidad del dueño de casa y le entregan a su esposa como prenda de pago el vestido de la joven asesinada. Estupefecta y horrorizada la dueña dice que solo el dueño de la casa puede aceptar tal don y se lo entrega a su marido que instantáneamente se da cuenta del fin que ha corrido su hija.

Ingeri se esconde con un profundo sentido de culpa y de remordiemientos pero al final decide regresar a su casa y contar lo sucedido a los padres de Karin.

A partir de ese momento cada momento de la vida de Töre está destinado a planificar su venganza que finalmente lleva a cabo, aunque también se deja llevar por el odio y termina matando al niño inocente.

El sentido metafórico del film, tal vez el más bello, es la escena final.

Mirándose las manos manchadas de sangre Töre exclama: "Ves Dios? Donde estás que no has impedido la muerte de un inocente y peor aún no has impedido mi venganza? No te entiendo!

Cuando los padres e Ingeri van al bosque a rescatar el cuerpo de la hija y darle cristiana sepultura, al moverlo, en el preciso lugar donde estaba su cabeza comienza a surgir un manantial de agua purísima.

Una película a la vez simple y maravillosa en la cuál el uso de la palabra -tan contrariamente a muchas películas en la actualidad- es reducido al mínimo indispensable, pasando largas secuencias en un silecio absoluto, dejando que sean la calidad de la fotografía (obviamente en blanco y negro) y la justa calibración de la banda sonora a crear una atmósfera mística que es rota brutalmente por el crimen más atroz.

Los personajes que Ingmar Bergman nos presenta en El Manantial de la Doncella se debaten a medio camino, sin lograr identificarse plenamente con ninguno, entre la adhesión al carácter divino espiritualmente religioso que todo lo comprende y todo lo justifica y el carácter real y humano del dolor terrenal, que solo es capaz de dar respuestas instintivas como el odio y la venganza.

Ambos padres están encerrados en este dilema. La madre Märeta, que es la más fiel a Dios, soporta la enorme, aplastante y terrible prueba de la fe como único medio para soportar el asesinato de su única hija.

Su esposo, en cambio, Töre, por más que vida en una familia con raigambres cristianas, sigue ligado a la dimensión pagana de su fe y al concepto de "ojo por ojo y diente por diente", la venganza absoluta, llevando a cabo una venganza despiadada contra todas las personas involucradas en la violación y el asesinato de su hija, que hayan participado activamente o no, no interesa. Y que entre los culpables se halle un joven inocente tampoco.

Las imágenes finales del manantial de agua que corre por donde estaba la cabeza de su hija y su firme promesa (a Dios) de construir una iglesia para pedir perdón es la culminación de la reflexión bergmaniana sobre la actitud del hombre que trata de adherir a lo divino aún cumpliendo un acto de salvaje naturaleza.

- Max von Sydow como Töre

- Birgitta Valberg como Märeta

- Birgitta Pettersson como Karin

- Gunnel Lindblom como Ingeri

Parábola sagrada y cuento pagano, obra de altísimo rigor expresivo, La Fuente de la Virgen de Ingmar Bergman surge como una toma de conciencia de la angustia entre la Fe y la duda, poco antes del "silencio de Dios". Oscar a la mejor película extranjera. Uno de los clásicos universales del cine.

At the height of his artistic maturity, when he already had 20 films behind him as a director, Ingmar Bergman directed one of the most emblematic and iconic works (not only in the religious sense) of his entire career, The Maiden's Spring, based on a Swedish legend from the 14th century.

Not only because of the awards it won (the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1960 would serve as a prelude to the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film and the Golden Globe for the same concept the following year (1961), but also because it is the only film directed by Bergman in which the religious theme - always present in his works - ends up coinciding in its human and divine aspects.

In medieval Sweden in the 14th century, tradition has it that a virgin maiden places candles to the Virgin Mary on a feast day.

The wealthy landowner Töre (Max von Sydow's wonderful performance) who believes in the Christian God, but uses a pagan ritual (boiling water and tree branches performed before the final outcome) commissions his daughter Karin, beautiful, candid and innocent, to carry out such a mission, accompanied by Ingeri, a dishonoured young woman - she has become pregnant after suffering carnal violence - and a pagan (she spends her days worshipping the god Odin).

During the journey two shepherds accompanied by a boy see the copy pass by, stalk them and finally attack them, raping and killing the young Karin - the boy does not participate - while Ingeri flees. In fact he does not even try to help her with his conscience and willpower eaten away by envy for the young girl.

In their flight the shepherds pose as stray shepherds and seek refuge - unbeknownst to them - in Karin's father's house.

After having eaten and rested, the criminals try to repay the kindness of the owner of the house and give his wife the dress of the murdered girl as a pledge of payment. Stupefied and horrified, the landlady says that only the owner of the house can accept such a gift and gives it to her husband, who instantly realises the fate of his daughter.

Ingeri goes into hiding with a deep sense of guilt and remorse but eventually decides to return home and tell Karin's parents what has happened.

From that moment on, every moment of Töre's life is devoted to planning his revenge, which he finally carries out, although he is also driven by hatred and ends up killing the innocent child.

The metaphorical sense of the film, perhaps the most beautiful, is the final scene.

Looking at his bloodstained hands, Töre exclaims: "See God? Where are you that you have not prevented the death of an innocent and worse still you have not prevented my revenge? I do not understand you!

When the parents and Ingeri go to the forest to rescue the body of their daughter and give it a Christian burial, when they move it, a spring of pure water begins to flow from the very place where her head was.

A film both simple and marvellous in which the use of words - so contrary to many films nowadays - is reduced to the indispensable minimum, spending long sequences in absolute silence, leaving it to the quality of the photography (obviously in black and white) and the right calibration of the soundtrack to create a mystical atmosphere that is brutally broken by the most atrocious crime.

The characters Ingmar Bergman presents us with in The Virgin Spring are torn between adherence to the spiritually religious divine character that understands and justifies everything, and the real and human character of earthly pain, which is only capable of instinctive responses such as hatred and revenge, without fully identifying with any of them.

Both parents are locked in this dilemma. Mother Märeta, who is the most faithful to God, endures the enormous, crushing and terrible ordeal of faith as the only means to endure the murder of her only daughter.

Her husband Töre, on the other hand, even though he lives in a family with Christian roots, remains attached to the pagan dimension of his faith and the concept of "an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth", absolute vengeance, carrying out a merciless revenge against all those involved in the rape and murder of his daughter, whether they actively participated or not does not matter. And whether an innocent young man is among the culprits doesn't matter either.

The final images of the spring of water flowing where her daughter's head was and her firm promise (to God) to build a church to ask for forgiveness is the culmination of Bergman's reflection on the attitude of the man who tries to adhere to the divine even while carrying out an act of savage nature.

And then he asks God an explicit question when his daughter's corpse is found. However, it is in him that the definitive conversion takes place with the promise to build a church to ask for forgiveness, with the subsequent divine manifestation through the miracle of spring. In both figures, it is a new Bergmanian reflection on the (un)human possibility of selfless love, i.e. whether it is possible for man to adhere to the divine with a full act of love that overcomes contingent interests. Is this God's legitimate request within human possibilities? And is it possible to strip oneself in historical times to the point of loving the other beyond all selfishness? If love often hides a comforting desire for domination and possession, what margins are left for true attachment to the other?

Max von Sydow as Töre

Birgitta Valberg as Märeta

Birgitta Pettersson as Karin

Gunnel Lindblom as Ingeri

A sacred parable and a pagan tale, a highly expressive work, The Fountain of the Virgin by Ingmar Bergman emerges as an awareness of the anguish between Faith and doubt, shortly before the "silence of God". Oscar for best foreign film. One of the universal classics of cinema.

Source images/Fuente de las imagenes: IMDB.

Separadores de textos /Divider text: PNG EGG

¡Nos vemos y leemos en la próxima reseña de cine amigo/as @blurtians!!

See you and read in the next film review friend / as @blurtians!