To understand how OpenOffice has evolved to its current form, we must look at the past and its current competitor: LibreOffice. (Part 2).

I remember that when I was young (quite a few years ago) talking about a word processor-editor was talking about Word, with capital or lower case. In the popular imagination everything was synonymous with Windows.

And although today there are remnants of that idea, it is clear that there are many text editors, with more or less functionality, that have been gaining ground on the super product from Microsoft.

And one of them is, without a doubt, on its own merits, OpenOffice.

But how did this text editor come to compete for a market share inch by inch with the strongest computer corporation and monopoly in the world.

In this post I finish telling you my impressions.

The golden years of OpenOffice (2000-2005).

The move to open source brought with it an explosion of improvements that fed into Sun's "commercial" version, StarOffice.

Both versions continued to exist in parallel, but the open source version was the one that drove the innovation.

Translations, which would go from 12 in StarOffice to the current 110, were added as the suite gained in popularity.

By 2003, OO.org had surpassed twenty million downloads, and ran on Windows, Linux, Mac, and other Unix flavors.

From the beginning, OpenOffice was committed to open document standards in XML format (OpenDocument), very different from the closed formats of Offices. The initial standard, called OpenOffice.org XML, was replaced by OpenDocument in 2005.

The goal of OpenDocument is to ensure universal access to computer documents, something difficult to protect when using proprietary formats such as those of Office. Sun, through OpenOffice, led the battle for the standard.

Initially, the use of different formats was costly, as Office was not able to read OpenOffice documents until version 2007 SP2. On the other hand, OpenOffice had always strived to improve compatibility with MS Office.

In 2005, OpenOffice.org reached version 2.0, which was more compatible with Microsoft Office. Sun Microsystems' support for the developer community – StarOffice continued to be distributed in parallel – was key to the health of the project.

That same year, the fact that OpenOffice needed a Java virtual machine to work at 100% provoked the ire of Richard Stallman, champion of free software, who referred to a "Java trap" when talking about OpenOffice.

Game of thrones and licenses (2006-2009).

From the very beginning, many developers were dissatisfied with the way Sun treated the programming community. The project was owned by Sun, but Sun's contribution in terms of programmers was 30%.

There was talk of very long testing times and excessive bureaucracy. With Sun having full control over the project, the community felt that it was not really in a position to innovate or decide, a situation that soon became unbearable.

To add to the dissatisfaction, IBM created its own variant of OpenOffice in 2007, called IBM Lotus Symphony, something that the code license allowed it to do. This variant survived until 2012, when it was reintegrated into the OpenOffice code.

But that was not the only episode of rebellion. Shortly before version 3.0 was released, another variant of OpenOffice, Go-oo, appeared, driven by Ximian (Novell) due to the slowness with which Sun accepted external patches.

Despite these difficulties, OpenOffice launched version 3.0 in 2008. It included numerous improvements - more than 500 - as well as a revamped interface. The market share was close to 15%, with tens of millions of downloads for each new version.

But Sun was not in good health, and several computing giants, including IBM, considered buying it. The final buyer of Sun was Oracle, which with Sun also acquired its open source projects.

The Oracle schism: LibreOffice is born (2009-2011).

Oracle, a database giant, bought Sun Microsystems on April 20, 2009 for the staggering sum of 7.4 billion dollars. The press release mentioned Java and Solaris, but nothing about OpenOffice. It was a bad sign.

The aesthetics of this screen indicate that something was not right...

At first, Oracle seemed to support the OpenOffice project, with a couple of versions that followed between 2010 and 2011. However, Oracle demonstrated from the beginning an inability even greater than that of Sun.

On September 28, 2010, the diaspora of developers disenchanted with Oracle created The Document Foundation, with the purpose of maintaining the original spirit of the OpenOffice project in an open and transparent collaborative environment.

Michael Meeks, a developer at Novell and the head of TDF, invited Oracle to join the the initiative was rejected by Oracle. Ubuntu, IBM and Go-oo, on the other hand, supported the project and the derivative version, which was renamed LibreOffice.

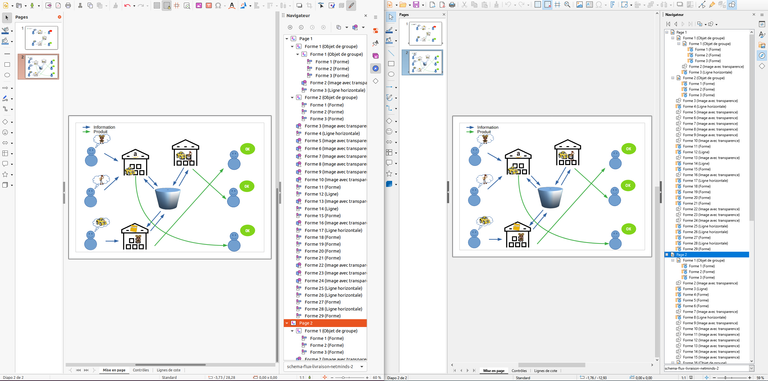

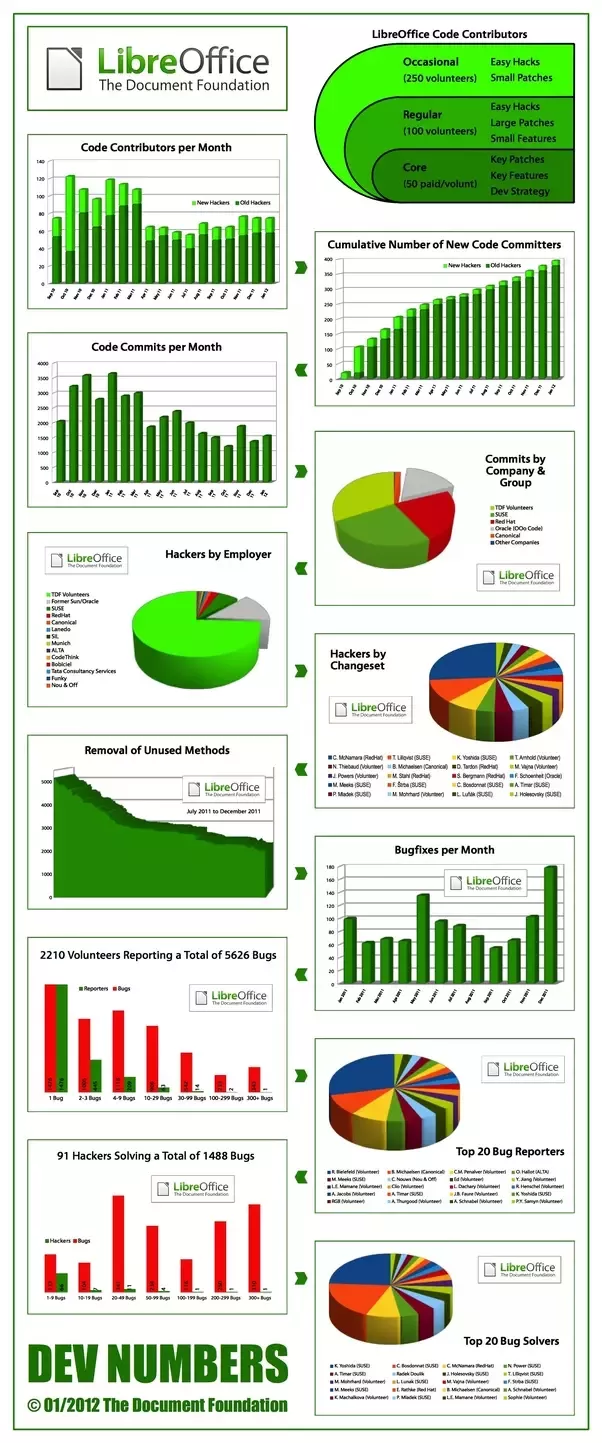

The first days of activity in the LibreOffice project

LibreOffice breathed new life into the project. Version 3.4, released in June 2011, featured substantial improvements in the code, some of which were cleaning up junk code and reducing the dependency on Java.

Apache comes to the rescue (2011-present).

The time came when Oracle said enough, and gave the OpenOffice code to the Apache Foundation, under the aegis of IBM. The conversations between the TDF and Apache began almost immediately in a climate of tense cordiality.

Oracle's was a poisoned gift: by giving the code to the Apache Foundation, the possibility of merging LibreOffice and OpenOffice was ruled out. The differences between the two projects in terms of rules, licenses and expectations were "very different."

The current situation, after several versions developed in parallel, is calm. LibreOffice and Apache OpenOffice develop and publish their versions with little coordination. While LibreOffice advances quickly, Apache OpenOffice limps along.

It is a sad situation for the free software community. OpenOffice, barely supported by volunteers, is practically stagnant. Those who do hold high the flag of alternative office automation are LibreOffice and the TDF - for now.

An uncertain future full of clouds.

Office automation is changing. There are already millions of people who use Google Drive or Prezi instead of Office when creating documents. Suites like Office strive to get closer to the Cloud, but with uncertain results.

The OpenOffice and LibreOffice projects, weakened by years of internal struggles, sterile discussions and bureaucratic obstacles, are doomed to extinction. The feeling of stagnation is palpable. OpenOffice has long since gone into hibernation.

Wherever a traditional office suite is still required, such as in public administration, projects of LibreOffice's calibre will continue to have loyal users (a recent example was the Munich city council).

But what about the mass of users that Sun dreamed of luring away from Microsoft Office? They have apparently gone to the Cloud. And there is little that OpenOffice or LibreOffice can do there, especially if they remain disunited.

Recuerdo que cuando era joven (hace ya bastante años) hablar de un procesador-editor de textos era hablar de Word, con mayúsculas o minúsculas. En el imaginario popular todo era sinónimo de Windows.

Y aunque en la actualidad quedan resabios de esa idea, es evidente que hay muchos editores de textos, con más o menos funcionalidades, que le han ido ganando terreno al super producto de casa Microsoft.

Y uno de ellos es, sin lugar a duda, por méritos propios, OpenOffice.

Pero como llegó este editor de texto a disputarle una feta de mercado palmo a palmo a la corporación informática y monopólica más fuerte del mundo.

En este post termino de contarles mis impresiones.

El lustro dorado de OpenOffice (2000-2005).

El paso al código abierto supuso una explosión de mejoras que iban alimentando a la versión "comercial" de Sun, StarOffice.

Ambas versiones siguieron existiendo en paralelo, pero la que empujaba el carro de la innovación era la de código abierto.

Las traducciones, que pasarían de las 12 de StarOffice a las 110 actuales, se añadían conforme la suite ganaba en popularidad.

En 2003, OO.org había superado los veinte millones de descargas, y funcionaba en Windows, Linux, Mac y otros sabores de Unix.

Desde el principio, OpenOffice se comprometió con estándares de documentos abiertos en formato XML (OpenDocument), muy diferentes a los formatos cerrados de Offices. El estándar inicial, llamado OpenOffice.org XML, fue sustituido por OpenDocument en 2005.

El objetivo de OpenDocument es garantizar el acceso universal a los documentos informáticos, algo difícil de proteger cuando se usan formatos propietarios como los de Office. Sun, a través de OpenOffice, encabezó la batalla por el estándar.

Inicialmente, el uso de formatos distintos fue costoso, ya que Office no fue capaz de leer documentos de OpenOffice hasta la versión 2007 SP2. Por otro lado, OpenOffice siempre se había esforzado en mejorar la compatibilidad con MS Office.

En 2005, OpenOffice.org alcanzó la versión 2.0, más compatible con Microsoft Office. El apoyo de Sun Microsystems a la comunidad de desarrolladores –StarOffice seguía distribuyéndose en paralelo- era clave para la salud del proyecto.

Ese mismo año, el hecho de que OpenOffice necesitase una máquina virtual de Java para funcionar al 100% provocó la ira de Richard Stallman, paladín del software libre, quien se refirió a una "trampa de Java" al hablar de OpenOffice.

Juego de tronos y licencias (2006-2009).

Ya desde el comienzo, muchos desarroladores no estaban satisfechos con la forma con que Sun trataba a la comunidad de programadores. La propiedad del proyecto era de Sun, pero la aportación de esta en términos de programadores era de un 30%.

Se hablaba de tiempos de prueba muy largos y un exceso de burocracia. Al tener Sun pleno control sobre el proyecto, la comunidad sentía que no estaba realmente en posición de innovar o decidir, una situación que pronto se hizo insoportable.

Para añadir más insatisfacción, IBM creó en 2007 su propia variante de OpenOffice, llamada IBM Lotus Symphony, algo que la licencia del código permitía hacer. Esta variante sobrevivió hasta 2012, año en que sería reintegrada en el código de OpenOffice.

Pero ese no fue el único episodio de rebeldía. Poco antes de que se lanzara la versión 3.0, apareció otra variante de OpenOffice, Go-oo, impulsada por Ximian (Novell) debido a la lentitud con la que Sun aceptaba parches externos.

A pesar de estas dificultades, OpenOffice estrenó en 2008 la version 3.0. Incluía numerosas mejoras -más de 500-, así como una interfaz renovada. La cuota de mercado rozaba el 15%, con decenas de millones de descargas para cada nueva versión.

Pero Sun no gozaba de buena salud, y varios grandes de la computación, entre ellos IBM, se plantearon su compra. Quien efectuó finalmente la compra de Sun fue Oracle, que con Sun adquiría también sus proyectos de código abierto.

El cisma de Oracle: nace LibreOffice (2009-2011).

Oracle, gigante de las bases de datos, compró Sun Microsystems el 20 de abril de 2009 por la escalofriante suma de 7,4 mil millones de dólares. En la nota de prensa se mencionaban Java y Solaris, pero nada acerca de OpenOffice. Era una mala señal.

La estética de esta pantalla indica que algo no iba bien...

Al principio, Oracle pareció apoyar el proyecto OpenOffice, con un par de versiones que se sucedieron entre 2010 y 2011. Sin embargo, Oracle demostró desde el principio una incapacidad todavía mayor que la de Sun.

El 28 de septiembre de 2010, la diáspora de desarrolladores desencantados con Oracle creó The Document Foundation, con el propósito de mantener el espíritu original del proyecto OpenOffice en un entorno de colaboración abierta y transparente.

Michael Meeks, desarrollador de Novell y cabeza visible de TDF, invitó a Oracle unirse a la iniciativa, pero esta rehusó. Ubuntu, IBM y Go-oo, por otro lado, apoyaron el proyecto y la versión derivada, que pasó a llamarse LibreOffice.

Los primeros días de actividad en el proyecto LibreOffice.

LibreOffice insufló nueva vida al proyecto. La versión 3.4, lanzada en junio de 2011, presentaba mejoras sustanciales en el código, algunas de los cuales fueron de limpieza de código basura y reducción de la dependencia con Java.

Apache acude al rescate (2011-actualidad).

Llegó el momento en que Oracle dijo basta, y cedió el código de OpenOffice a la fundación Apache, bajo la égida de IBM. Las conversaciones entre la TDF y Apache empezaron casi de inmediato en un clima de tensa cordialidad.

El de Oracle fue un regalo envenenado: al ceder el código a la fundación Apache, la posibilidad de fusionar LibreOffice y OpenOffice se descartó. Las diferencias entre ambos proyectos en cuanto a reglas, licencias y expectativas eran "muy diferentes".

La situación actual, después de varias versiones desarrolladas en paralelo, es de calma. LibreOffice y Apache OpenOffice desarrollan y publican sus versiones con escasa coordinación. Mientras LibreOffice avanza rápido, Apache OpenOffice renquea.

Es una situación triste para la comunidad del software libre. OpenOffice, sostenida a duras penas por voluntarios, se encuentra prácticamente estancada. Quien sí mantiene alta la bandera de la ofimática alternativa es LibreOffice y la TDF -por ahora-.

Un futuro incierto y repleto de nubes.

La ofimática está cambiando. Son ya millones las personas que usan Google Drive o Prezi en lugar de Office a la hora de crear documentos. Suites como Office se esfuerzan por acercarse a la Nube, pero con resultados inciertos.

Los proyectos OpenOffice y LibreOffice, debilitados por años de luchas intestinas, discusiones estériles y obstáculos burocráticos, se hallan abocados a la extinción. La sensación de estancamiento es palpable. Hace tiempo que OpenOffice hibernó.

Allá donde siga siendo necesario usar una suite ofimática tradicional, como en la administración pública, proyectos del calibre de LibreOffice seguirán teniendo usuarios fieles (un ejemplo reciente lo dio el ayuntamiento de Munich).

Pero ¿y la gran masa de usuarios que Sun soñaba con alejar de Microsoft Office? Esos, al parecer, se han ido a la Nube. Y allí hay poco que OpenOffice o LibreOffice puedan hacer, sobre todo si siguen desunidos.

- Sources/Fuentes:

| Blogs, Sitios Web y Redes Sociales / Blogs, Webs & Social Networks | Plataformas de Contenidos/ Contents Platforms |

|---|---|

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Los Apuntes de Tux |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | El Mundo de Ubuntu |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Nel Regno di Linux |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Linuxlandit & The Conqueror Worm |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Pianeta Ubuntu |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Re Ubuntu |

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Nel Regno di Ubuntu |

| Red Social Twitter / Twitter Social Network | @hugorep |

| Blurt Official | Blurt.one | BeBlurt | Blurt Buzz |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|---|

Re🤬eD

Libre!

🥓

Thanks!

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Thanks @ctime.