3 Distributed LMS Synchronization

3.1 Learning Content Sharing

Before going to the main discussion of synchronization, it is better to discuss about learning content sharing. Sharing learning contents became popular ever since MOOC was introduced. A course "Moodle on MOOC" conducted periodically teaches students how to use Moodle and advised them to share their finished courses [16]. Making a well designed and written learning contents for online course from a scratch may consume a lot of time, learning content sharing helps other instructors to quickly develop their own. Some specialized courses may only be written by experts. Learning content sharing reduces the burden of the teacher to create learning contents for online courses, and the more the existence of online courses can give more students from all over the world a better chance to access a quality education.

Distributed LMS is also another form of learning content sharing where the learning contents are shared to other servers on other regions. The typical way of learning content sharing is dump, copy, then upload. Most LMS have a feature to export their course contents into an archive and allows to import the contents to another server which have the LMS. The technique to export and import varies to systems but the concept is to synchronize the directory structure and database. There is a very high demand for this feature that it is still improving until now, for example being able to export user defined part of the contents is being developed. Other LMS that currently does not have this feature will be developed as it is stated on its developer forum.

3.2 Full Synchronization versus Incremental Synchronization

3.2.1 Full Synchronization

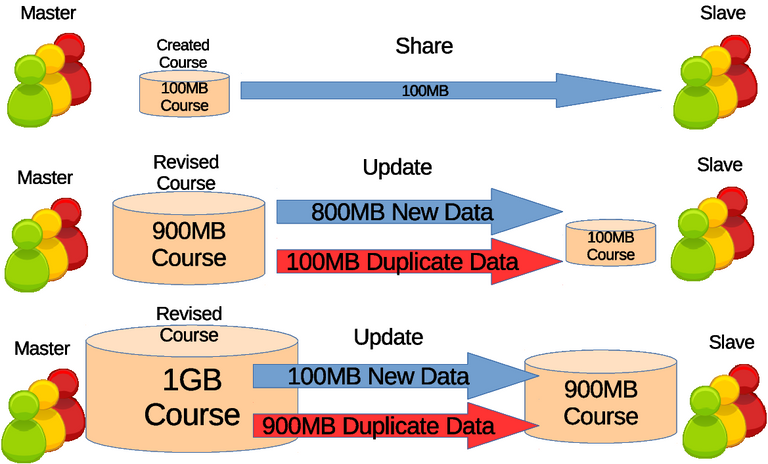

Synchronization can be defined as similar movements between two or more systems which are temporally aligned, though on this case is the action of causing a set of data or files to remain identical in more than one location. The data or files are learning contents and private data, although private data are usually excluded. The term full synchronization defined on this thesis is the distribution of the whole data consists of new data and existed data. Synchronization occurs when new data are present to update the data of other servers. Illustrated on Figure 3.1 the full synchronization includes existed or duplicated data which deems to be redundant that only adds unnecessary burden to the network. However full synchronization are more reliable because each full data are available.

Figure 3.1 Illustration of full synchronization of learning contents in courses. Initial stage is learning content sharing where 100 mega bytes (MB) of course is shared. Next stage is update where there is 800MB of new data but whole 900MB is transfered which 100MB is a duplicate data. On next update there is 100MB of new data but whole 1GB is transfered which 900MB is duplicate data.

3.2.2 Incremental Synchronization

Ideally the duplicate data are to be filtered out and not to be distributed for highest efficiency. The conventional way is the recording approach where the changes done by the authors of the course are recorded. The changes can only and either be additions or deletions of certain locations. This actions are recorded and sent to other servers and have them execute the actions to achieve identical learning contents, which is similar to push mechanism where the main server forces updates on other servers. Accurate changes can be obtained but unrecoverable from error because the process is unrepeatable. Another issue is its restriction that no modification must take place on the learning contents of other servers, meaning the slightest change, corruption, or mutation can render the servers unsynchronizable.

Instead of the recording approach, the calculating approach is more popular due to its repeatable process and less restriction. The approach is to calculate the difference between the new and outdated learning contents. Therefore the process of the approach can be done repeatedly and some changes, corruption, or mutation on either learning contents does not prevent the synchronization. One of the origins of the calculating approach is file differential algorithm developed in Bell Laboratory [17] which today known as diff utility in Unix. The detailed algorithm may seem complicated, though in summary consists of extracting the common longest subsequence of characters in each line between the two files (more like finding the similarity between two files), afterwards the rest of the characters on the old file will be deleted while on the new file the characters will be added to the common longest subsequence on the correct location, resulting in update of the old file. For large files hashings were involved.

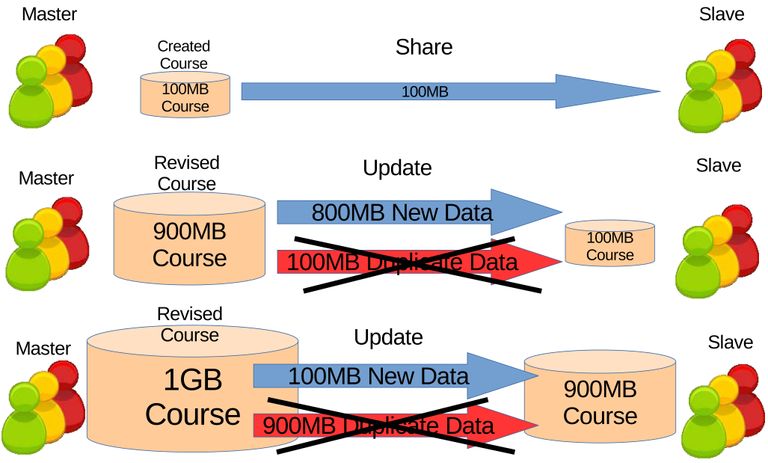

Applying the file differential algorithm on the synchronization will make it differential synchronization. Unlike full synchronization, differential synchronization is the distribution of only the new data. The repetition of differential synchronization will make it incremental synchronization which is the repetitive distribution of only the new data. In sense the synchronization will be incremental because only the updates are sent every time. Another way to put it, increment means to add up where the learning contents adds up to every differential updates. Ultimately duplicate data or learning contents will be filtered out, reducing unnecessary burdens on the network illustrated on Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 Incremental synchronization different from Figure Figure 3.1 where the duplicate data are filtered.

3.2.3 Dynamic Content Synchronization on Moodle

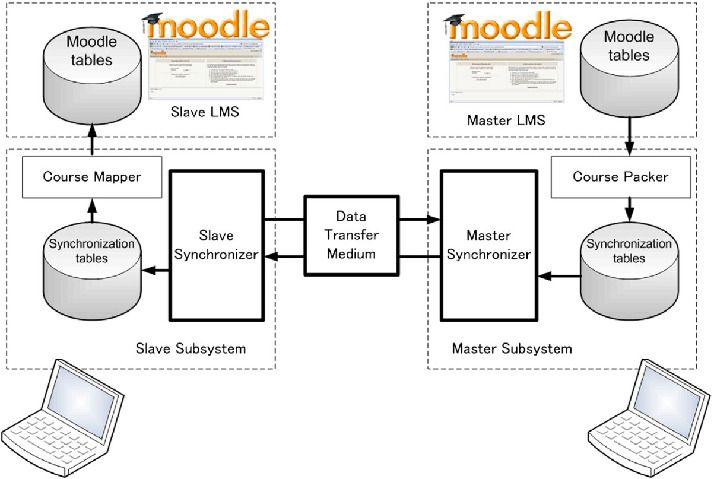

The idea of implementing differential synchronization on distributed LMS started by Usagawa et al. [18], which then continued by Ijtihadie et al. [11] [19]. These works still limits themselves to distributed Moodle system because it solely focuses on Moodle structure. When writing the software application, it is necessary to identify the database tables and directories of the learning contents. The incremental synchronization between two Moodle systems was described as dynamic content synchronization [11] where the learning contents are constantly being updated. The dynamic synchronization is unidirectional or simplex in terms of communication model where it is fixed that one Moodle system acts as a master to distribute the updates and another one acts as a slave to receive the updates.

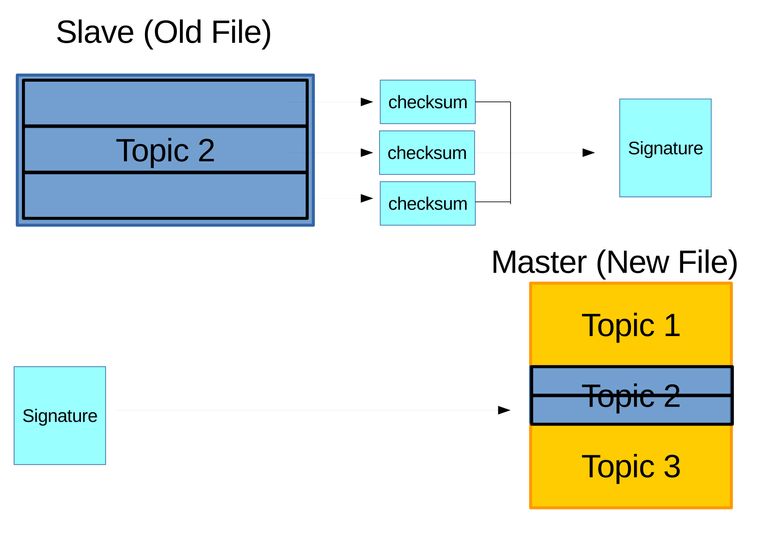

File differential algorithm was applied to maintain consistencies on both master's and slave's database tables and directories. The database tables and directories are assigned with hashes [11]. Information of those hashes are exchanged between master and slave, identical hashes meaning thoses contents should not be change, and on the other hand mismatch hashes meaning those contents should be updated. Though Ijtihadie et al. [11] developed their own algorithm stated specifically for synchronization of learning contents between LMS, it is not much different from existing remote differential file synchronization algorithm such as [20].

The moodle tables on the database is converted into synchronization tables as on Figure 3.3 through means of hashing. Only contents related to the selected course was converted and sorted on the course packer. Privacy was highly regarded, thus private data was filtered. The purpose is to find inconsistencies on the database between master and slave. Stated on the previous paragraph, hashes are oftenly used to test inconsistencies, if the hashes are different then they are inconsistent and vice versa. When inconsistencies on a certain table is found, the master sends its table to the slave replacing the slave's table which in the end will become consistent. In the end the synchronization tables are reverted back into Moodle tables. In summary dynamic content synchronization only takes place on parts of the database and directories that changes or inconsistent.

Figure 3.3 Dynamic content synchronization model for Moodle [11]. The course packer converts both Moodle tables into synchronization tables. Then the synchronizer checks for inconsistency between the two tables which in the end applies the difference between both synchronization table to the slave’s synchronization table. Finally the synchronization table is reconverted into Moodle table and that is how it is synchronized.

3.3 Dump and Upload Based Synchronization

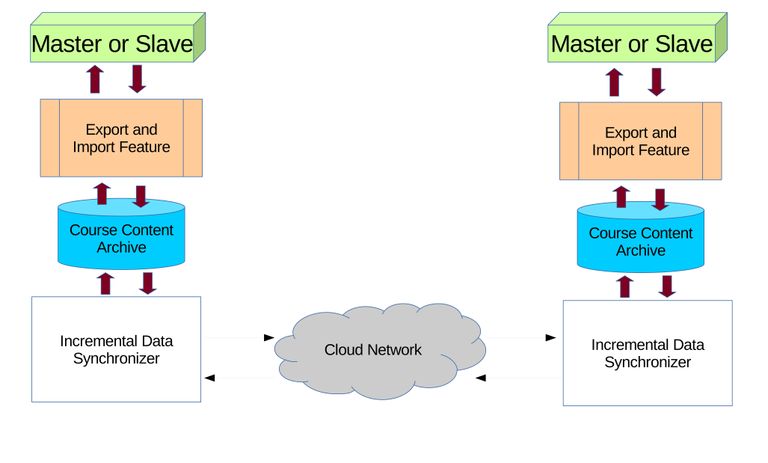

The dynamic content synchronization [11] software application was written solely for Moodle, and back then was written for Moodle version 1.9. Later on Moodle rises to version 2.0, with major changes on database and directory structure. The software application have to be changed to suit the new Moodle version [19], but the concept of synchronization remains the same. Moodle continues to develop, until now it is version 3.3, though sadly the dynamic content synchronization software application was discontinued on Moodle version 2.0. The author originally tried to continue the software application but found a better approach named dump and upload based synchronization model [12] on Figure 3.4. Unlike dynamic content synchronization, the dump and upload based synchronization is bidirectional but limited to half duplex communication model. In other words each can play as both master and slave, but only one at time. For example, on first synchronization one server can play as the master while others as slaves, and on second synchronization the master can switch into a slave and one of the slaves can switch into a master. Another thing is that the synchronization uses pull mechanism where the slave checks and requests updates to the master. It is considered more flexible than the push mechanism where the master forcefully update the slaves.

Figure 3.4 The dump and upload based synchronization model. Both servers' LMS will dump/export the desired learning contents (in this case packed into a course) into archives/files. The synchronizer will perform differential synchronization between the two archives. After synchronization the archives will be imported/uploaded into the servers' LMS, updating the learning contents.

3.3.1 Export and Import Feature

While dynamic content synchronization handles everything from a scratch, the dump and upload based synchronization utilizes the export and import feature that exists in most LMS. It is a feature mainly to export and import learning contents categorized into courses which can also be called course contents. The export feature outputs the course content's database tables and directories into a structured format. Then the import feature reads the format and inserts the data into the correct database tables and directories. Formats may differ from one LMS to another but the method is most likely the same.

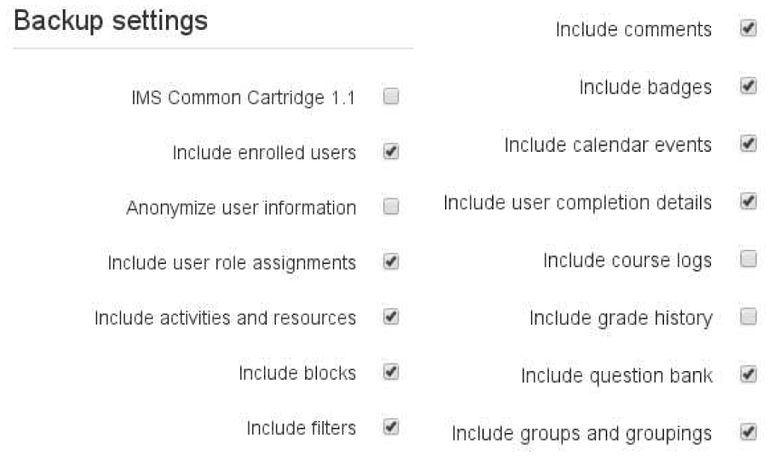

Other features are export and import of course lists, user accounts, and probably more others but not known and used on this thesis. One of the best export and import is on Moodle where further splitting is possible on the course contents while on other LMS have to dump the whole course. This way people can choose to get only the contents they are interested in. This opens a path for partial synchronization where only specific contents or parts of the course are synchronized. Another advantage is the option to choose to include, not to include private data, or include private data but anonymized, in other words it supports privacy. In summary Moodle's export and import feature's advantage compared to other LMSs' is the ability to secure private data, and split course contents into blocks or micros screenshot on Figure 3.5. This thesis highly recommends other LMSs' export and import feature to follow Moodle's footsteps.

Figure 3.5 Screenshot of Moodle's export feature, (a) showed options like include accounts, and (b) showed learning contents to choose to export.

3.3.2 Rsync a Blocked Based Remote Differential Algorithm

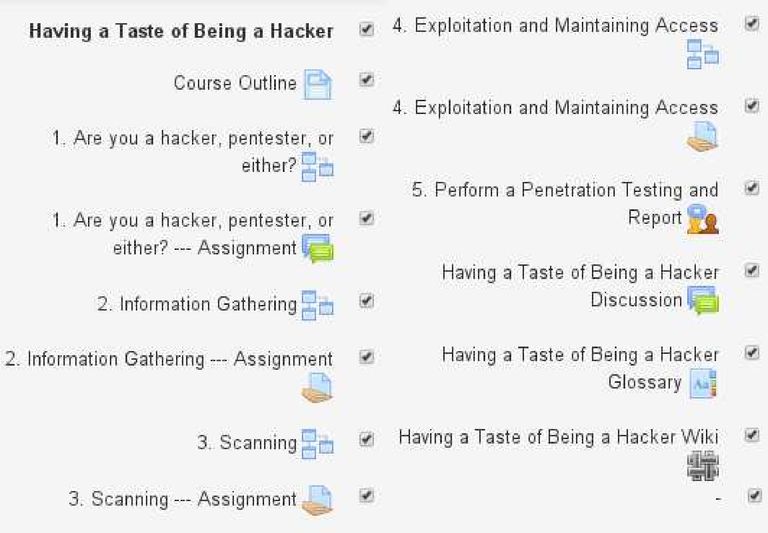

With the pervious subsection explained that course contents can be dumped using the export and import feature, the next step is performing remote differential synchronization between the two archives. The author chose not to develop an algorithm but used an existing algorithm called rsync [20]. The author also did not write a program to perform rsync but use the already existing program based on the rsync library (librsync). What the author did is just implementing this program to work on hyper text transfer protocol (HTTP) or on web browsers since LMS are usually web based (rsync is mostly used on secure shell (SSH)). There are three general steps of performing rsync algorithm between the two archives located on different servers as on Figure 3.6, and details are as follow:

Figure 3.6 First step is to generate a signature of archive on slave and send to master. The signature of is used on master's archive to generate delta/patch or can be called the difference and have it sent to slave. Slave will apply/use that delta/patch on its archive and produce an archive identical to the one on master.

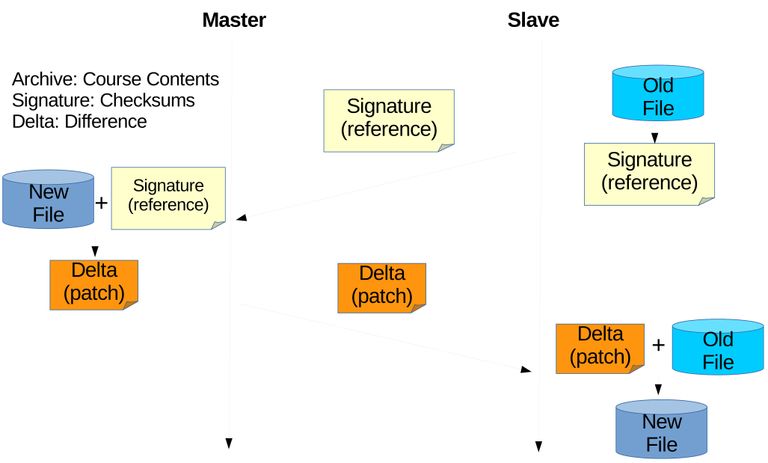

- The archive to be updated is divided into blocks with each blocks calculated and assigned two types of hash or checksums. The checksums are weak rolling checksum for example Adler-32 and strong checksum for example Black2, and MD5. The checksums are bundled into a signature and sent to the other server. The user can determine the size of divided blocks which can affect the accuracy of finding difference. Figure 3.7 illustrates this step.

Figure 3.7 Assume two archives where the outdated archive on slave have only second topic, and latest archive on master have all three topics. Here for example outdated archive is divided into three blocks, and three sets of checksums are obtained and bundled into a signature. The signauture is then sent to master.

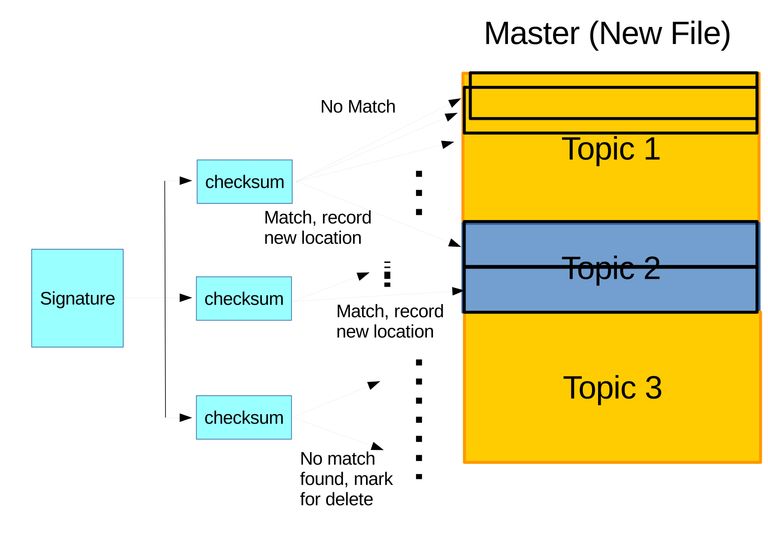

- The signature is then used on the latest version archive on the server with latest version of archive. First a weak checksum is checked in rolling block. Second if a block's weak checksum is identical then comparison of the two strong checksums is done to verify whether the block is really identical or not. For blocks with identical checksums, their locations are recorded, while other blocks are regarded as new blocks which should be sent to the server with outdated archive. Checksums on signature with no matching blocks found on archive with latest verstion, the blocks of the outdated archive that generated this checksum will be regarded as deleted. Based on all of these information a delta/patch is generated containing instructions to alter the blocks of the outdated archive and new blocks to be inserted there. This step is illustrated on Figure 3.8.

Figure 3.8 Illustration of identifying difference. (a) The three sets of checksums are compared in rolling with other blocks on new archive. Identical blocks to the first and second sets of checksums are found and the locations are recorded while no matching block is found for the third set of checksums which will be marked for delete. (b) The delta is generated on master containing instructions to rearrange identical blocks, delete unfounded blocks, and append new blocks, which will be send and applied on slave.

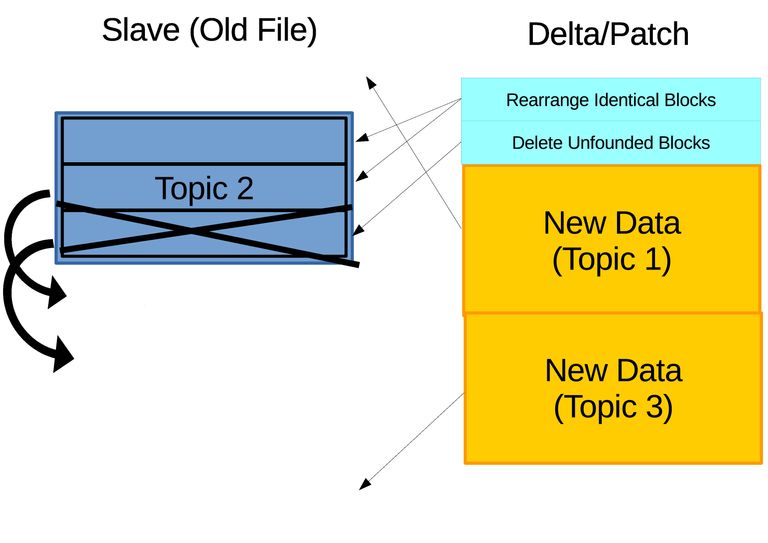

- The delta/patch is sent to the server with outdated archive, applying it to its archive, constructing identical archive to the latest version one as on Figure 3.9.

Figure 3.9 After the delta/patch is applied, slave will have identical archive to master.

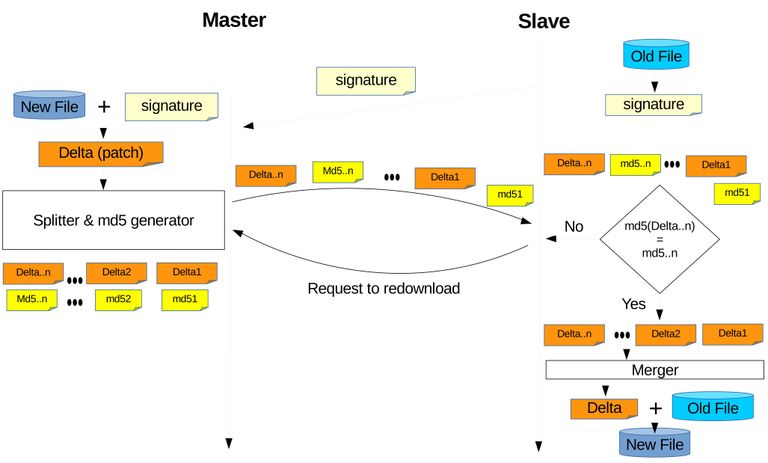

Lastly on this subsection, for implementation should be targeted for regions with severe network connectivity. Although transmitting only the differential than the whole contents reduces the transmission cost, it is not the only answer regarding to network stability issue. Network stability issue can be a long cut off in the middle of transmission which forces to restart the synchronization process. Another one is short cut offs which makes the transmission discrete but unnecessary to restart, however frequent short cut offs can corrupt the transmission data. To solve this unstable network problem, techniques implemented in most download manager software applications should also be implemented on the synchronization's transmission. To support continueable download after the transmission is completely cutoff, is to split the transmission data into pieces. During cutoff, the transmission can be continued by detecting how much pieces the client has, then request and retrieve remaining pieces from server. To prevent data corruption checksums can be used to verify the data's integrity, on this case are the pieces integrity. Finally Figure 3.6 is modified to Figure 3.10.

Figure 3.10 Implementation of some download manager techniques into rsync algorithm based synchronization. Delta is split into pieces and retrieved by the client. The integrity of the pieces are checked using cheksum, here is MD5 and if inconsistent it will redownload those pieces. In the end the pieces are merged. This can also be implemented on uplink side when sending the signature.

3.3.3 Experiment Result and Evaluation

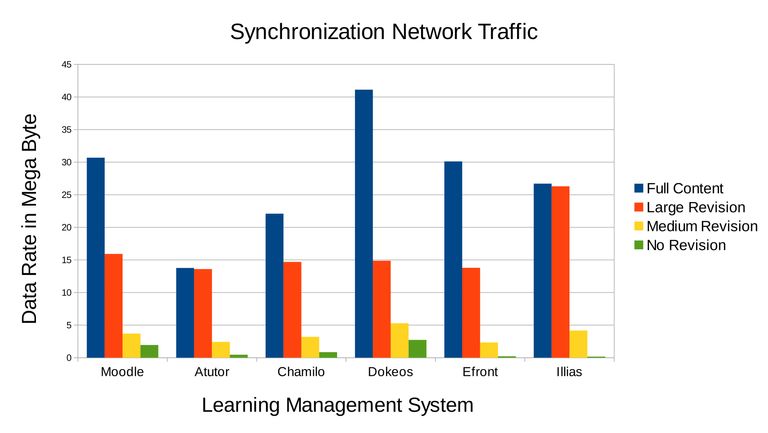

With dump and upload based synchronization prototype created, an experiment was conducted. The experiments took place on many LMS with the latest version, which were Moodle 3.3, Atutor 2.2.2, Chamilo 1.11.4, Dokeos 3.0, Efront 3.6.15.5, and Illias 5.2. The purpose was to compare the network traffic between full synchronization and incremental synchronization, and percentage of duplicate data eliminated. The experiment used the authors own original course contents which mainly consists three topics are computer programming, computer network, and penetration testing, with each consists of materials, discussion forums, assignments, and quizzes. A snapshot of one of the topics was provided on Figure Figure 3.3.

There are four scenarios. First is full synchronization, equivalent to transmitting the whole course content or full download from the client side. Second is large content incremental synchronization is when the client only have one of the three topics (example for Moodle will update from 16.5MB to 30.5MB). Third is medium content incremental synchronization is when the client already have two of the three topics (example for Moodle will update from 28.4MB to 30.5MB), and the client wants to synchronize to the server in order to have all three of the topics (update). Fourth is no revision meaning incremental synchronizing while there is no update, to test whether there are bugs in the software application which the desired result should be almost no network traffic generated. On Table 3.1 shows the course content data size in bytes when it has one, two, or three of the topics. The data sizes varies depending on the LMS, but the contents such as materials, discussion forums, assignments, and quizzes are almost exactly similar.

| LMS | 1 Topic | 2 Topics | 3 Topics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moodle | 16.5 MB | 28.4 MB | 30.5 MB |

| Atutor | 336.5 kB | 11.7 MB | 13.7 MB |

| Chamilo | 8.5 MB | 20 MB | 22 MB |

| Dokeos | 27.4 MB | 39 MB | 41 MB |

| Efront | 16.5 MB | 28 MB | 30 MB |

| Illias | 439.3 kB | 22.8 MB | 26.6 MB |

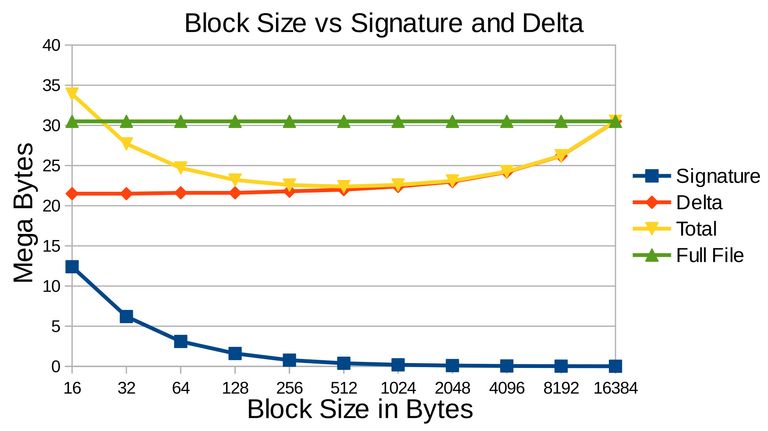

The experiment used rdiff utilities to perform rsync algorithm between latest and outdated as the incremental synchronization. Before proceeding it is wise to examine the affect of block size which on previous subsection states that users are free to define the size. The test was perform on Moodle's archives from Table Table 3.1 between an archive which has one topic of 16.5MB and archive which has 3 topics of 30.5MB. The result is on Figure 3.11 showing the relationship between block size, signature, and delta size, which affects total transmission cost by summing signature and delta. Larger block size meaning less blocks where less checksum sets are generated, thus smaller signature size. However this means less accurate checking and less likely to detect similar blocks which will contribute to the size of the delta. The Figure 3.11 showed the delta had reached the full size of the targeted archive, meaning that it missed detecting similar blocks, thus the whole archive is treated as totally different archive. The incremental synchronization will be more heavier than full synchronization. Reversely smaller block size provides more accurate detection which guarantee to reduce the size of the delta. However this means more blocks and more checksum sets are to be bundled into the signature, and looking at the Figure it can grow very large that can cost a lot more transmission cost then full synchronization itself. In conclusion choosing the right blocksize is crucial to get less sum of signature and delta that contributes to the transmission cost, on this case 512 bytes of block size is optimum.

Figure 3.11 Test result showing the relationship between block size, signature, and delta. When the block size increases the signature size decreases, but the opposite for delta which it increases. The full file is the size of the file to be downloaded without using differential method, in other words using full synchronization. The transmission cost if using incremental synchronization is the sum of signature and delta which on this case is when the block size is 512 bytes when it is optimal.

With the relationship of blocksize to signature and delta discussed, it is still not ready to proceed with the experiment. With the difference between the two archive's size, latest is 30.5MB and outdated is 16.5MB ideally the delta should be 14MB but still strayed far to as large as 20MB. It is found that the problem is because the rsync algorithm (rdiff) was executed directly on the archive which is still compressed. The solution is to uncompress the archive before hand and execute rdiff recursively of every available contents which makes the author to turn on more modified utility called rdiffdir.

The experiment succeeded and got results of Figure 3.12. Figure 3.12 already includes uplink and downlink, for incremental synchronization uplink is influenced by the size of the signature and downlink is influenced by the size of the delta (see Figure 3.6). Detailed data are also provided on Table 3.2. However the purpose of both Figure 3.12 and Table 3.2 is only to show that incremental synchronization is better than full synchronization which in this case is lower network traffic, and to show that the incremental synchronization is able to detect when there are no updates in this case almost no network traffic, while the main objective is to eliminate duplicate data during transmission.

Figure 3.12 Network traffic generated based on the four scenarios of the experiment. Full sychronization generates the most network traffic shown in blue bars. The orange and yellow bar is network traffic of incremental synchronization depending on the size of contents to be updated which lower are generated compared to full synchronization. The green bars showed incremental synchronization execution when there is no update and the results are very low and tolerable.

| Signature in Mega Bytes | Delta in Mega Bytes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMS | Large | Medium | None | Large | Medium | None |

| Moodle | 0.5427 | 0.9668 | 1.1621 | 15.7489 | 2.9688 | 0.7227 |

| Atutor | 0.0292 | 0.3125 | 0.3711 | 13.5254 | 2.0899 | 0.0684 |

| Chamilo | 0.215 | 0.5427 | 0.6144 | 14.4282 | 2.6214 | 0.2048 |

| Dokeos | 1.307 | 1.6282 | 1.6794 | 15.0938 | 3.6535 | 0.9626 |

| Efront | 0.1024 | 0.1741 | 0.1946 | 13.6499 | 2.1402 | 0.0102 |

| Illias | 0.0025 | 0.1339 | 0.1559 | 26.2226 | 4.0107 | 0.0001 |

| Average | 0.3671 | 0.6264 | 0.6962 | 16.4431 | 2.9141 | 0.3281 |

The percentage of redundant data eliminated is shown on Table 3.3 for incremental synchronization scenarios. It is assumed that the ideal delta is the difference in data size between the latest and outdated archive. The duplicate data is the outdated archive itself or the latest archive substracted by the ideal delta, which is this much that had to be eliminated. The larger the experiment's delta size compared to the ideal delta, the worse the experiment's result. With these results the performance of the incremental synchronization can be evaluated by calculating the percentage of duplicated data eliminated which is the full latest archive substracted by experiment's delta size, next divided by duplicated data, and then converted to percentage. For large content synchronization there is one LMS Atutor which had a low result of 51.89 % due to size of generated archive itself (Table Table 3.1) and drop the whole average to 85.30%. Other than Atutor and Illias the duplicate data eliminated percentage is above 89%. For the medium content synchronization a very high average duplicate data eliminated percentage is achieve which is 97.90%, meaning duplicate data are almost completely eliminated. Though these results are obtain strictly under optimal block size configuration (Figure Figure 3.11) where the minimum network traffic consisted of uplink and downlink (affected by signature and delta size) is desired. There is no benefit of 100% duplicate data elimination if the uplink (signature size) is very large.

| In Mega Bytes | Large Content Synchronization | Medium Content Synchronization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMS | Full | Result | Ideal | Eliminated | Result | Ideal | Eliminated |

| Moodle | 30.5 | 15.7389 | 14 | 89.46% | 2.9688 | 2.1 | 96.94% |

| Atutor | 13.7 | 13.5254 | 13.3635 | 51.89% | 2.0899 | 2 | 99.23% |

| Chamilo | 22 | 14.4282 | 13.5 | 89.08% | 2.6214 | 2 | 96.89% |

| Dokeos | 41 | 15.0938 | 13.6 | 95.55% | 3.6535 | 2 | 95.76% |

| Efront | 30 | 13.6499 | 13.5 | 99.09% | 2.1402 | 2 | 99.50% |

| Illias | 26.6 | 26.2226 | 26.1697 | 87.71% | 4.0106 | 3.8 | 99.08% |

| Average | 27.3 | 16.4431 | 15.6889 | 85.30% | 2.9141 | 2.3167 | 97.90% |

3.3.4 Advantage of Dump and Upload Based Synchronization

With the dump and upload based incremental synchronization model successfully able to eliminate very large amount of duplicate data the advantage compared to the previous dynamic content synchronization can be discussed:

- Since the model utilizes existing utilities mainly the export and import feature in LMSs one software application can be compatible to all LMS and all of its versions as long as it has this feature. The reason is because the export and import feature is guaranteedly maintain by the LMSs' developers, unlike dynamic content sychronization software application, there is no need to worry about structure changes on LMS. The advantage is actually on the developer side, when writing dynamic content synchronization software application the writer needs to coordinate the database and directories while for dump and upload based synchronziation it is already taken care of by the LMSs' developers.

- Other benefits can also be obtained from the export and import feature however relative to the LMS. For example on Moodle it has the capability to choose whether to include private data or not, meaning for synchronization it can have a flexible privacy option. While for other LMS private data is filtered out which means no other options other than retaining the privacy for synchronization. Another example also on Moodle it is able split a course into smaller blocks of learning contents and able to dump specific learning contents (not all). The synchronization software application can be tuned for partial synchronization, meaning other teachers can get only parts that they are interested in. Unfortunately this is available only on Moodle, other LMS have to dump the whole course contents.

- Since the method is dumping, it can easily be tuned for bidirectional synchronization, unlike dynamic content synchronization which is unidirectional. The incremental synchronization uses the pull concept where the requesting server only asked the difference from targeted server, while push concept is usually unidirectional where the master forcefully updates the slaves. Although dynamic content synchronization is claimed to be unidirectional, the author sees that it is possible to modify the software application to bidirectional because the differential synchronization method is general, however it is uknown whether it will be as easy to modify as the dump and upload base synchronization.

4 Conclusion and Future Work

4.1 Conclusion

Portable and synchronized distributed LMS was introduced to keep the contents up to date in environment of severe network connectivity. By replacing the servers with hand carry servers, the servers in severed network regions were able to move to find network connectivity for synchronization. The hand carry server was proved to be very portable because of its very small size and very light weight. The power consumption is very low that a power bank used on smart phone is enough to run the hand carry server for almost a whole day. Though very convenient however it has resource limitations mainly on CPU and memory, which limits the number of concurrent users. Still, the problem of unable to perform synchronization in no network connectivity area is solved.

The Incremental synchronization technique was beneficial for synchronization in distributed LMS, where it eliminates very large amount of duplicate data . Though in the past incremental synchronization was already proposed to be implemented in distributed LMS, this thesis provides a better approach which is dump and upload based synchronization. The advantages are that it is compatible to most LMSs and most of their versions, easily tuneable for bidirectional synchronization, and because it utilizes LMS features it can be tuned for example to configure privacy settings, and to perform partial synchronization.

4.2 Future Work

All of the experiment are done in the lab, and it is better to conduct real implementation in the future especially regarding the hand carry servers. A possible real implementation is to have drones carrying the hand carry servers. Performance issue is still a problem with hand carry servers that demands for enhancing techniques like integrating field programmable gate array (FPGA). For incremental synchronization it was discussed only the network issue but not yet resource such as CPU and memory. Although the synchronization on this thesis is bidirectional, distributed revision control system is needed to be implemented for larger collaborations. The distributed LMS here is a replicated system, but there is a better, more flexible trend to use especially for content sharing which is message oriented middleware (MOM) system that in the future is very interesting to be implemented.

Acknowledgement

I would like to give my outmost gratitude to the all mighty that created me and this world for his oportunity and permission to walk this path as a scholar and for all his hidden guidances.

The first person I would like to thank is my main supervisor Prof. Tsuyoshi Usagawa for giving me this topic, also to Dr. Royyana who was researching on this topic before me, and their countless wise advices for perfecting this research. The professor is also the one who gave me this oportunity to enroll in this Master's program in Graduate School of Science and Technology, Kumamoto University. It was also through his recommendation that I received the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) scholarship from Japan. Not to forget his invitation to join his laboratory, the facilities, and comfort that he had provided. Also, I would like to thank all the oportunities that he had given me to join many conferences such as in Tokyo, Myanmmar, and Hongkong.

Then I would like to thank the Japanese government for giving me this MEXT scholarship that I never have to worry about financial. Instead I can focus on my studies, research, planning my goals for the future, and helping other people. I also would like to thank my other supervisors Prof. Kenichi Sugitani and Prof. Kohichi Ogata for evaluating my research and my thesis.

Next I would like to thank my parents, family and my previous University Udayana University, for not only raising and allowing me, but also pushed me to continue my studies. I would to thank my project team Hendarmawan and Muhammad Bagus Andra that our work about hand carry servers contributes in forming this thesis. My project team also my friends in laboratory Alvin Fungai, Elphas Lisalitsa, Irwansyah, Raphael Masson, and Chen Zheng Yang who were mostly on my side and even contributes to some degree on all my research. Like my friends in previous University whom now walk our separate ways, often spent the night together in laboratory, are friends whom I can trust with my life.

I would to like thank the Indonesia Community, Japanese friends, and other international friends who helped me with life here for example finding an apartment for me, but mostly their friendliness. Lastly to all others that helped me whom I cannot mention one by one, whether the known or the uknown, and whether the seen and the unseen. To all these people, I hope we can continue to work together in the future.

Reference

- M. Kelly, “openclipart-libreoffice,” (2017), [computer software] Available: http://www.openclipart.org. [Accessed 27 June 2017].

- S. Paturusi, Y. Chisaki, and T. Usagawa, “Assessing lecturers and students readiness for e-learning: A preliminary study at national university in north sulawesi indonesia,”GSTF Journal on Education (JEd), vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 18, (2015), doi: 10.5176/2345-7163_2.2.50

- Monmon. T, Thanda. W, May. Z. O, and T. Usagawa, “Students E-readiness for E-learning at Two Major Technological Universities in Myanmar,” In Seventh International Conference on Science and Engineering, pp. 299-303, (2016), Yangon, Myanmar.

- O. Sukhbaatar, L. Choimaa, and T. Usagawa, “Evaluation of Students’ e-Learning Readiness in National University of Mongolia, ” Educational Technology (ET) Technical Report on Colloborative Support, etc., pp. 37-40 (2017). Soka University:Institute of Electronics, Information and Communication Engineers (IEICE).

- E. Randall, “Mongolian Teen Aces an MIT Online Course, Then Gets Into MIT,” [online] Available: http://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/blog/2013/09/13/mongolian-teen-aces-mit-online-course-gets-mit. [Accessed 27 June 2017].

- N. S. A. M. Kusumo, F. B. Kurniawan, and N. I. Putri, “Learning obstacle faced by indonesian students,” in The Eighth International Conference on eLearning for Knowledge-Based Society, Thailand, Feb. (2012), [online] Available: http://elearningap.com/eLAP2011/Proceedings/paper25.pdf. [Accessed 27 June 2017].

- Miniwatts Marketing Group, “Internet World Stats Usage and Population Statistics,” [online] Available: http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm. [Accessed 27 June 2017].

- Q. Li, R. W. H. Lau, T. K. Shih, and F. W. B. Li, “Technology supports fordistributed and collaborative learning over the internet,” ACM Transactions onInternet Technology (TOIT) Journal, vol. 8, issue 2, no. 5, pp, (2008).

- F. Purnama, and T. Usagawa, “Incremental Synchronization Implementation on Survey using Hand Carry Server Raspberry Pi”,Educational Technology (ET)Technical Report on Colloborative Support, etc., pp. 21-24 (2017). Soka University: Institute of Electronics, Information and Communication Engineers (IEICE), doi: 10.1145/1323651.1323656.

- F. Purnama, M. Andra, Hendarmawan, T. Usagawa, and M. Iida, “Hand Carry Data Collecting Through Questionnaire and Quiz Alike Using Mini-computer Raspberry Pi”,International Mobile Learning Festival (IMLF), pp. 18-32 (2017), [online] Available: http://imlf.mobi/publications/IMLF2017Proceedings.pdf. [Accessed 27 June 2017].

- R. M. Ijtihadie, B. C. Hidayanto, A. Affandi, Y. Chisaki, and T. Usagawa, “Dynamic content synchronization between learning management systems over limited bandwidth network,” Human-centric Computing and Information Sciences, vol. 2,no. 1, pp. 117, (2012), doi: 10.1186/2192-1962-2-17

- F. Purnama, T. Usagawa, R. Ijtihadie, and Linawati, “Rsync and Rdiff imple-mentation on Moodle’s backup and restore feature for course synchronization overthe network”,IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP), pp. 24-29 (2016). Bali:IEEE, doi: 10.1109/TENCONSpring.2016.7519372.

- The World Bank Group. Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people). (2017,March 06). Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL.SETS.P2.

- R. M. Ijtihadie, Y. Chisaki, T. Usagawa, B. C. Hidayanto, and A. Affandi, “E-mail Based Updates Delivery in Unidirectional Content Synchronization among Learning Management Systems Over Limited Bandwidth Environment, ”IEEE Re-gion 10 Conference (TENCON), pp. 211215, (2011), doi: 10.1109/TENCON.2011.6129094.

- R. M. Ijtihadie, Y. Chisaki, T. Usagawa, B. C. Hidayanto, and A. Affandi, “Offline web application and quiz synchronization for e-learning activity for mobile browser” 2010 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), pp. 2402-2405, (2010), doi: 10.1109/TENCON.2010.5685899.

- M. Cooch, H. Foster, and E. Costello, “Our mooc with moodle," Position papers for European cooperation on MOOCs, EADTU, (2015).

- J. W. Hunt, and M. D. McIlroy, “An algorithm for differential file comparison,” Computing Science Technical Report, (1976). New Jersey: Bell Laboratories, [online] Available: https://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~doug/diff.pdf. [Accessed 27 June 2017].

- T. Usagawa, A. Affandi, B. C. Hidayanto, M. Rumbayan, T. Ishimura, and Y.Chisaki, “Dynamic synchronization of learning contents among distributed moodle systems,” JSET, pp 1011-1012, (2009).

- T. Usagawa, M. Yamaguchi, Y. Chisaki, R. M. Ijtihadie, and A. Affandi, “Dynamic synchronization of learning contents of distributed learning management systems over band limited network contents sharing between distributed moodle 2.0 series," in International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), (2013). Antalya, doi: 10.1109/ITHET.2013.6671058

- A. Tridgell and P. Mackerras, “The rsync algorithm," The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia, Tech. Rep. TR-CS-96-05, (1996), [online] Available: https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/40765. [Accessed 27 June 2017].