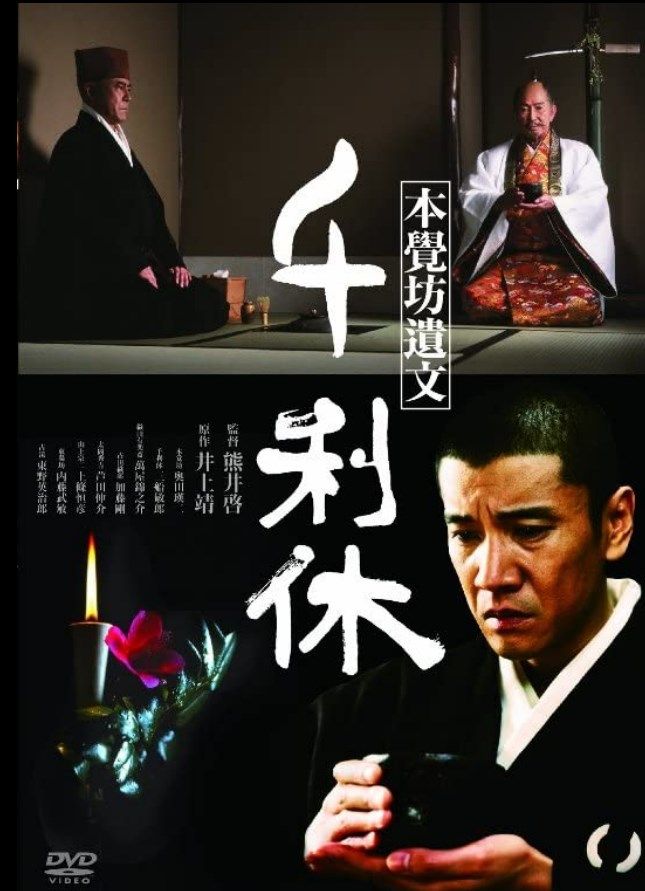

Death of a Tea Master is a drama film that won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1989.

It was a film that divided critics and juries to such an extent that the prize was awarded out of competition.

It is a film in the most traditional Japanese style: cold, intellectual, but not without great inner beauty.

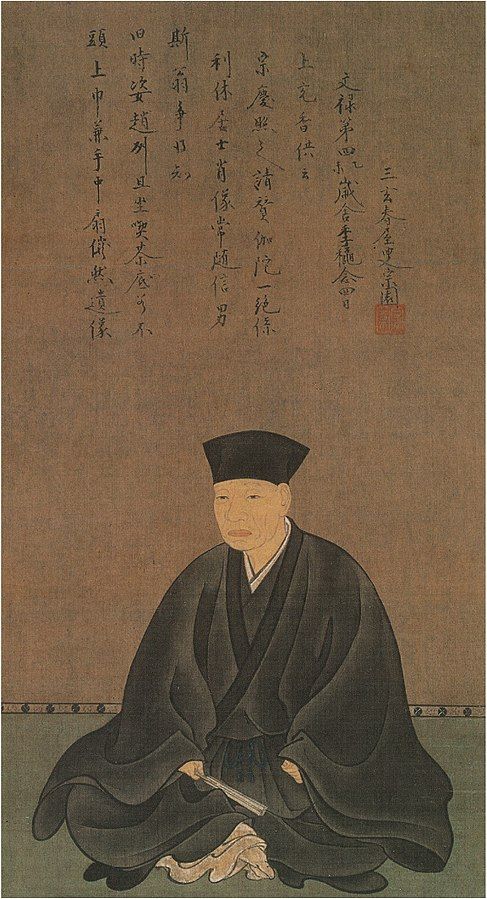

The plot is based on the last years of the life of Sen no Rikyū who lived in the 16th century, still considered today by his followers as the most emblematic and spiritually influential historical figure in the so-called "Japanese tea ceremony", particularly in the aspects referring to the wabi-cha tradition.

Muerte de un maestro del té es una película dramática que ganó el León de Plata (Ex aequo) en el Festival de Venecia en el año 1989.

Fue un film que dividió la crítica y los jurados a punto tal que el premio fue otorgado fuera de concurso.

Es una película en el más tradicional estilo japonés: fría, intelectual, pero no por eso carente de una gran belleza interior.

El argumento se basa en los últimos años de la vida de Sen no Rikyū que vivió en el siglo XVI, considerado aún hoy por sus seguidores como la figura histórica más emblemática y de mayor influencia espiritual en la llamada "ceremonia del té japonesa", particularmente en los aspectos que se refieren a la tradición wabi-cha.

Rikyū is the founder of the three main schools of tea ceremony in Japan: Urasenke, Omotesenke and Mushanokōjisenke, which together form the so-called san-Senke.

Rikyū committed suicide by committing harakiri, and the film tries, through the figure of his main disciple, to understand the reasons that led him to this decision.

The tea ceremony in feudal Japan was reserved for samurai who, after combat, would take a break and a cup of tea prepared by the Grand Master, to return to the battlefield from which many would surely not return.

The film is set in the early 17th century, almost three decades after the great tea master Sen no Rikyu has decided to end his life through a ritual sacrifice (harakiri) when two disciples of the revered master try to recall the past and understand the reasons that led the master to commit suicide.

One of them is Honkakubo, the great master's favourite, who after his death lives in dignified poverty and continually has dreams and visions in which the deceased (played by a wonderful Toshirō Mifune) appears to him.

Uraku, another of Rikyu's disciples, and Honkakubo try to recall the events that might have led the master to commit suicide by karakiri.

One suspicion is that Rikyu, a respectful guardian of the ethical essence and ancient forms of the tea ritual, and at the same time a stubborn opponent of some of the political ideas of the ruler Hideyoshi, may have refused to perform the ceremony for the purpose of furthering violent ends.

Hideyoshi enjoyed great prestige not only because he was emperor but also because he had succeeded in reunifying his country, invaded Korea and left a cultural legacy which, among other things, allowed only samurai to bear arms.

Rikyu's profoundly peaceful character contrasted with the warrior character of the monarch and for this reason he was exiled.

Faced with such humiliation, the only way out was a "dignified death" through harakiri.

Rikyū es el fundador de las tres principales escuelas de la ceremonia del té en Japón: Urasenke, Omotesenke y Mushanokōjisenke que, en conjunto, forman el llamado san-Senke.

Rikyū se suicidó haciéndose el harakiri y la película trata, a través de la figura de su principal discípulo, de entender las causas que lo llevaron a esa decisión.

La ceremonia del té en el Japón feudal estaba reservada a los samurai que, después del combate, se tomaban una pausa y una taza de té preparada por el gran Maestro, para volver a combatir al campo de batalla desde el cuál muchos seguramente no retornarían.

La película se sitúa temporalmente a inicios del siglo XVII, casi tres décadas después que el gran maestro del té Sen no Rikyu ha decido poner fin a su vida a través de un sacrificio ritual (harakiri) cuando dos discǐpulos del venerado maestro tratan de rememorar el pasado y entender los motivos que han llevado el maestro al suicidio.

Uno de ellos es Honkakubo el favorito del gran maestro quien después de la muerte de éste vive con digna pobreza y y tiene continuamente sueños y visiones en los que se le aparece el difunto (interpretado por un estupendo Toshirō Mifune.

Uraku, otro de los discípulos de Rikyu y junto con Honkakubo intentan recordar los acontecimientos que podrían haber llevado al maestro a suicidarse mediante el karakiri.

Una de las sospechas es que Rikyu, respetuoso guardián de la esencia ética y las antiguas formas del ritual del té, y la vez que tenaz opositor a algunas de las ideas políticas del soberano Hideyoshi, se haya negado a celebrar la ceremonia a los efectos de propiciar fines violentos.

Hideyoshi gozaba de un gran prestigio no solo por el hecho de ser emperador sino también porque había logrado reunificar su país, invadido la Corea y había dejado un legado cultural que entre otras cosas autorizaba a portar armas solo a los samurai.

El carácter profundamente pacífico de Rikyu constrataba con carácter guerrero del monarca y por este motivo fue exiliado.

Ante tal humillación la única salida era una "muerte digna" a través del harakiri.

Toshirō Mifune as Rikyu no Sen

Eiji Okuda as Honkakubo

Kinnosuke Yorozuya as Urakusai Oda

Go Kato as Oribe Furuta

Shinsuke Ashida as Hideyoshi Toyotomi

Toshirō Mifune como Rikyu no Sen

Eiji Okuda como Honkakubo

Kinnosuke Yorozuya como Urakusai Oda

Go Kato como Oribe Furuta

Shinsuke Ashida como Hideyoshi Toyotomi

More than intellectualism or coldness, I believe that this film tries to highlight the difficulty of understanding, of sharing some things that move us and that for a large part of the Asian continent, and especially for the Japanese, have little importance, or in other words, do not touch them in the same way as they do for the Latinos.

This millenary culture of little dialogue translates into the same cibe, with relatively little action, very slow moments, coldness in relationships and an almost total absence of emotion.

Some directors such as the brilliant Akira Kurosawa have managed to bring many of these archetypes to the cinema (often with the help of the extraordinary Toshiro Mifune) in films of notable importance. And it is not by chance that Kei Kumai was chosen to complete the last film of the great master Kurosawa, The Sea and Love.

Más que intelectualismo o frialdad, creo que esta película trata de poner de relieve la dificultad de entender, de compartir algunas cosas que nos conmueven y que para gran parte del continente asiático, y en especial para los japoneses, tienen poca importancia, o dicho de otro modo, no las tocan de la misma manera que lo hacen para los latinos.

Esta cultura milenaria del poco diálogo se traduce en el mismo cibe, con relativamente poca acción, momentos muy lentos, frialdad en las relaciones y una ausencia casi total de emoción.

Algunos directores como el genial Akira Kurosawa han conseguido llevar al cine muchos de estos arquetipos (a menudo con la ayuda del extraordinario Toshiro Mifune) en películas de notable importancia. Y no es casualidad que Kei Kumai fuera el elegido para completar la última película del gran maestro Kurosawa, El mar y el amor.

Source images / Fuente imágenes: IMDB.

| Blogs, Sitios Web y Redes Sociales / Blogs, Webs & Social Networks | Plataformas de Contenidos/ Contents Platforms |

|---|---|

| Mi Blog / My Blog | Cine & Series de Cabecera. |

| Red Social Twitter / Twitter Social Network | @hugorep |