Indeed, although research with postcards is currently considered as solid as any other -and that in the end, it has the same limitations as the study of other similar objects (Albers and James, 1988)- it was only in the 1980s (with some postmodern perspectives) that the reticence towards their use (and that of photography in general) as a documentary source that could be subjected to systematic analysis was progressively abandoned (Ferguson, 2005).

Thus, postcards have been the subject of analysis by researchers interested in different issues.

This includes, among other things, theoretical discussions and reflections on this particular means of communication and object of collection (Derrida, 1980 [2001]; Correia, 2009); its analysis as a form of reproduction of works of art (Correia, 2008); its function in times of war (Booth, 1996) and its association with the development of pornography through images (Sigel, 2000). In this set of topics, the link between postcards and tourism has clearly had a place of preeminence.

In the field of tourism studies, postcard images have received more attention than the texts that accompany them. These images have been analyzed seeking to understand how places and cultures are represented (Andriotis and Mavrič, 2013).

This type of postcard analysis focuses attention on tourist places/destinations or their inhabitants to see how they are portrayed today or historically.

Sometimes this analysis focuses attention on a particular aspect of those portrayed in the postcards - such as the Palestinian women presented differently in Israeli or Palestinian postcards analyzed by Moors (2003), or the postcards analyzed by Mellinger (1994) showing the stereotypical way of presenting the African American population of the southern United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In other works the focus is placed on the role of the postcard in certain processes such as, for example, the definition of American patriotism in connection with the development of car culture in the late nineteenth century (Gross, 2005); the ways of portraying nature as an identity referent in its link with nationalism (Winiwater, 2008) or the creation of discourses and practices associated with colonial domination and its link with tourism (Burns, 2004).

Other studies have focused attention on the texts that make up the postcards: among them are the compilation of postcards and the transcription of their messages by Phillips (2000); the recovery of postcard messages about African Americans reinforcing racial prejudice in the early twentieth century by Baldwin (1988); the analysis of the ideas, opinions and feelings expressed in the messages of postcards sent by students by Kennedy (2005). Recently some studies have attempted to go beyond these two aspects of the postcard (image and text/message) by inquiring into its status as an object: mobile object that moves along with tourists and through the postal service (Andriotis and Mavrič, 2013) and collectible object, in a use very similar to that given to the souvenir (Rogan, 2005; Schor, 1992).

The methodological challenges in studies addressing the relationship between postcards and tourism are not of a minor nature. Among the difficulties of working with this type of material are the impossibility of dating it, its ephemeral nature, the particularities of its availability, the lack of information on its circulation, the absence of data on the photo that composes it, etc. (Ferguson, 2005).

Likewise, the definition of the specific set of postcards analyzed by different authors is adjusted to various criteria and in some cases to the mere availability of these objects (provided for consultation in institutions, offered for sale, exhibited by collectors, etc.).

Thus, sometimes we work with postcards produced for a particular destination by a specific publishing house (Youngs, 2012; Harris, 1995¸ Corkery and Bailey, 1994); in other cases, we analyze the postcards available on a specific theme in an archive, library or museum (Sisti, 2010; Pritchard and Morgan, 2005), in others, as many postcards as possible on a place or thematic are collected (Andriotis and Mavrič, 2013), on other occasions personal collections of the authors themselves are resorted to in order to analyze the postcards or reflect on them (Schor, 1992; dos Santos Franco, 2006; Phillips, 2000).

But beyond the emphasis on one or another aspect of the postcard to be analyzed and the methodological decisions involved, the analyses of postcards in their link with tourism practice have been influenced by broader interpretative perspectives that have addressed the relationship between tourism and visual culture.

The importance of the sense of sight and different visual objects in tourism has been highlighted by several authors. Crawshaw and Urry (1997), for example, note that from the late eighteenth century onwards vision becomes a central organizing element in discourses on tourism and travel, adding that it is the visual images of places that give shape and meaning to modes of anticipation, tourist experience and travel memories. Undoubtedly, the most direct reference to this way of understanding the relationship between tourism and visuality is John Urry's concept of the tourist gaze (in The tourist gaze of 1990).

This concept does not refer exclusively to the intentional act of seeing that the idea of the gaze entails, but it also rescues its historical and socio-cultural dimensions to define the interest of tourism in certain objects and places. Although the author does not ignore the presence of other senses that shape the tourist experience, in his original approach sight takes a prominent place as a way of accessing information that is generated to be experienced and consumed visually. Urry (1996 [1990]) develops a semiological interpretation to argue that the tourist gaze is constructed from signs and that tourists (as practitioners of semiotics) look for pre-established signs in the landscape, those derived from discourses on travel and tourism.

Particularly in some of the works carried out from this perspective, the idea that different tourist visual materials (among others, for example, brochures, tourist guides and the postcards themselves) offer an institutionalized proposal to represent places and cultures (in which the tourist industry plays a central role) has been insisted upon. With specific reference to postcards, their participation in the affirmation of certain stereotypes and their role in the selections involved in the ways in which cultures and places are portrayed in tourism have also been emphasized (see Markwick, 2001, and Pritchard and Morgan, 2005).

Discussions around tourism and visual culture have, more recently, led to the definition of new perspectives of interpretation.

These new views are closely linked to the reflections that have been made about visual culture and the intensification of the “modern tendency to image or visualize experience” that characterizes today's culture (Mirzoeff, 2003; 23).

Thus, for example, Crouch and Lübbren (2003), addressing the tourism/visual culture relationship, propose to focus not only on visual objects -such as photographs, tourist brochures, postcards- but also on all the relationships established between objects, practices, expectations, experiences, ideologies, etc., understood as elements that constitute a broader network (Crouch and Lübbren, 2003). In their proposal, they also relativize the primacy historically attributed to the sense of sight in relation to tourism, pointing out the need to analyze the visual dimension of the tourist experience together with other sensory dimensions.

Traditionally, when addressing the relationship established in the processes of production and consumption (of images, among other things) linked to tourism practice, a polarized scheme was used in which it was assumed that the production of images and ideas about objects and places of tourist interest were generated by those actors interested in the development of tourism (entrepreneurs, public agencies), while the consumption of these proposed images and ideas was reserved for the tourist (Crouch, 2004; Scarles and Lester, 2013). Currently, and recovering conceptual developments linked to the discussion of the structure/agency relationship (see MacCannell, 2001), tourists are also considered to be active actors in the production of images (Crang, 1997). The revision of the sharp or dichotomous divisions between the spheres of production and consumption in tourism leads to relativizing the influence that certain intentional images and ideas can exert on the tourist without ignoring the importance of essential aspects for understanding tourism (among them, the role of actors linked to the deliberate construction of certain representations; Crouch, 2004).

Also, in the light of new conceptual developments that, assuming that today's society is a mobile society, try new ways of understanding different visual objects, including postcards. This line includes works that attempt to place under analysis other aspects of the postcard besides image and text. An example of this is the work of Andriotis and Mavri (2013) who use the New Mobilities Paradigm proposed by John Urry to analyze the postcard under five interrelated forms of mobility: bodily mobility, imaginative mobility, communicative mobility, virtual mobility and object mobility. His intention is to approach the postcard not only as a way of presenting places but also as an object of inquiry that represents, entails and enables these interdependent forms of mobility and all the systems involved in them.

La inclusión de postales (y de otro tipo de materiales visuales) en la investigación social es relativamente reciente.

En efecto, a pesar de que la investigación con postales es considerada en la actualidad tan sólida como cualquier otra ‑y que en definitiva, presenta las mismas limitaciones que el estudio de otros objetos similares (Albers y James, 1988)‑ fue recién a partir de la década de 1980 (de mano de algunas perspectivas posmodernas) que progresivamente se abandonaron las reticencias hacia su uso (y al de la fotografía en general) como fuente documental que podía ser sometida a un análisis sistemático (Ferguson, 2005).

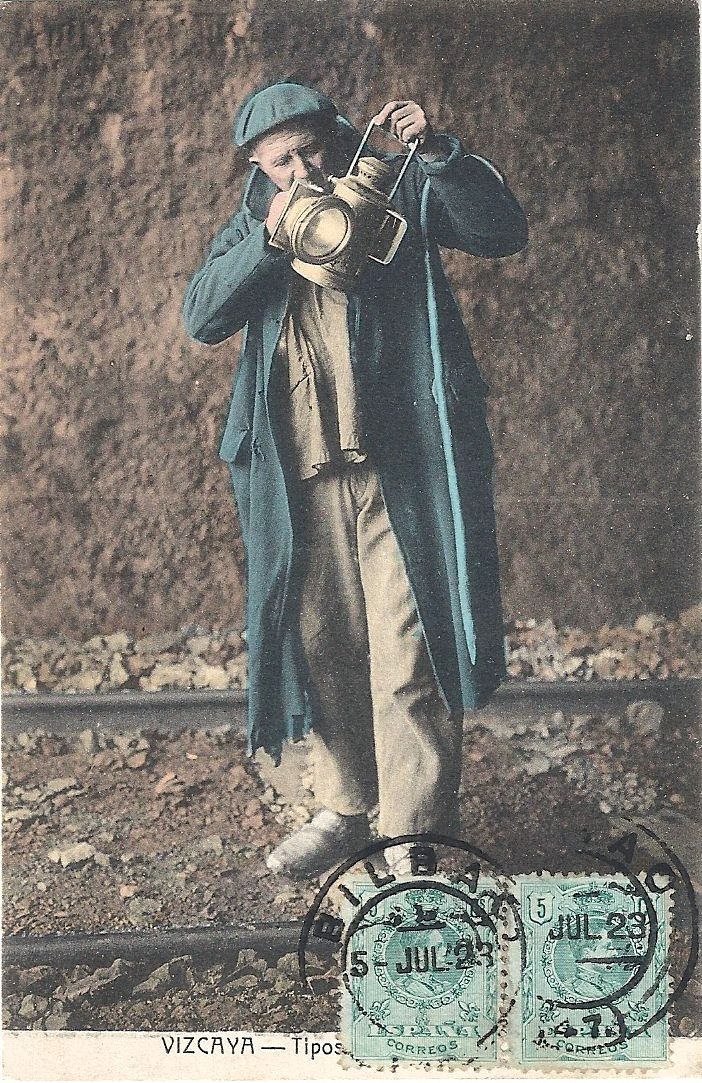

Ferroviario de Vizcaya (España). Tarjeta postal circulada en el año 1923. Fototipia coloreada a mano.

Así, las postales han sido objeto de análisis de investigadores interesados en distintas cuestiones.

Esto incluye, entre otras cosas, discusiones teóricas y reflexiones en torno a este medio de comunicación y objeto de colección particular (Derrida, 1980 [2001]; Correia, 2009); su análisis como una forma de reproducción de obras de arte (Correia, 2008); su función en tiempos de guerra (Booth, 1996) y su asociación con el desarrollo de la pornografía a través de imágenes (Sigel, 2000). En este conjunto de temáticas la vinculación de las postales con el turismo ha tenido, claramente, un lugar de preeminencia.

Desde el campo de los estudios sobre el turismo, las imágenes de las postales han recibido mayor atención que los textos que las acompañan. Estas imágenes han sido analizadas buscando conocer de qué manera lugares y culturas son representados (Andriotis y Mavrič, 2013). Este tipo de análisis de postales focalizan la atención en lugares/destinos turísticos o en sus habitantes para ver cómo son retratados en la actualidad o históricamente.

En ocasiones este análisis centra la atención en algún aspecto en particular de quienes son retratados en las postales ‑como las mujeres palestinas presentadas de manera diferente en postales israelíes o palestinas que analiza Moors (2003), o las postales analizadas por Mellinger (1994) que muestran la manera estereotipada de presentar a la población afroamericana del sur de Estados Unidos hacia fines del siglo XIX y comienzos del siglo XX. En otros trabajos el foco se coloca en el papel de la postal en determinados procesos tales como, por ejemplo, la definición del patriotismo norteamericano en vinculación con el desarrollo de la cultura del automóvil a fines del siglo XIX (Gross, 2005); las formas de retratar la naturaleza como referente identitario en su vinculación con el nacionalismo (Winiwater, 2008) o la creación de discursos y prácticas asociados a la dominación colonial y su vinculación con el turismo (Burns, 2004).

Otros estudios han focalizado la atención en los textos que componen las postales: entre ellos se encuentra la compilación de postales y la transcripción de sus mensajes realizada por Phillips (2000); la recuperación de los mensajes de postales sobre afroamericanos reforzando prejuicios raciales a comienzos del siglo XX de Baldwin (1988); el análisis de las ideas, opiniones y sentimientos expresados en los mensajes de las postales enviadas por estudiantes realizado por Kennedy (2005). Recientemente algunos estudios han intentado ir más allá de estos dos aspectos de la postal (imagen y texto/mensaje) indagando en su condición de objeto: objeto móvil que se desplaza junto con los turistas y a través del servicio postal (Andriotis y Mavrič, 2013) y objeto coleccionable, en un uso muy similar al que se le otorga al souvenir (Rogan, 2005; Schor, 1992).

Los desafíos metodológicos en los estudios que abordan la relación entre postales y turismo no tienen un carácter menor. Entre las dificultades que presenta el trabajo con este tipo de materiales suelen señalarse la imposibilidad de datar, su carácter efímero, las particularidades de su disponibilidad, la falta de información sobre su circulación, la ausencia de datos respecto de la foto que la compone, etc.(Ferguson, 2005).

Asimismo, la definición del conjunto concreto de postales analizadas por distintos autores se ajusta a criterios variados y en algunos casos a la mera disponibilidad de estos objetos (brindados para su consulta en instituciones, ofrecidos a la venta, exhibidos por coleccionistas, etc.).

Así, en ocasiones se trabaja con postales elaboradas para un destino en particular por alguna casa de edición específica (Youngs, 2012; Harris, 1995¸ Corkery y Bailey, 1994); en otras, se analizan las postales disponibles sobre una temática en algún archivo, biblioteca o museo (Sisti, 2010; Pritchard y Morgan, 2005), en otras se recolectan tantas postales como sea posible sobre un lugar o temática (Andriotis y Mavrič, 2013), en otras oportunidades se recurren a colecciones personales de los propios autores para analizar las postales o reflexionar sobre ellas (Schor, 1992; dos Santos Franco, 2006; Phillips, 2000).

Pero más allá del énfasis en uno u otro aspecto de la postal a ser analizada y de las decisiones metodológicas implicadas, los análisis de las postales en su vinculación con la práctica turística han estado influidos por perspectivas de interpretación más amplias que han abordado la relación entre el turismo y la cultura visual.

La importancia del sentido de la vista y los diferentes objetos visuales en el turismo ha sido puesto de manifiesto por varios autores. Crawshaw y Urry (1997), por ejemplo, observan que a partir de fines del siglo XVIII la visión se vuelve un elemento que organiza de manera central los discursos relativos al turismo y a los viajes, añadiendo que son las imágenes visuales de los lugares las que dan forma y significado a los modos de anticipación, a la experiencia turística y a los recuerdos del viaje. Sin dudas, la referencia más directa a esta forma de entender la relación entre turismo y visualidad es el concepto de mirada turística de John Urry (en The tourist gaze de 1990).

Este concepto no hace referencia exclusivamente al acto de ver intencionado que comporta la idea de mirada, sino que, además, rescata sus dimensiones históricas y socioculturales para definir el interés del turismo hacia determinados objetos y lugares. Si bien el autor no ignora la presencia de otros sentidos que dan forma a la experiencia turística , en su planteo original la vista toma un lugar destacado como modo de acceder a la información que es generada para ser experimentada y consumida visualmente. Urry (1996 [1990]) desarrolla una interpretación semiológica para sostener que la mirada turística es construida a partir de signos y que los turistas (como practicantes de semiótica) buscan en el paisaje signos preestablecidos, aquellos que derivan de discursos sobre viajes y turismo.

Particularmente en algunos de los trabajos realizados desde esta perspectiva se ha insistido en la idea de que distintos materiales visuales turísticos (entre otros, por ejemplo, folletos, guías turísticas y las propias postales) ofrecen una propuesta institucionalizada de representar lugares y culturas (en la que la industria turística tiene un rol central). En referencia específicamente a las postales, también se ha enfatizado su participación en la afirmación de determinados estereotipos y su rol en las selecciones involucradas en las formas de retratar turísticamente culturas y lugares (ver Markwick, 2001, y Pritchard y Morgan, 2005).

Las discusiones en torno al turismo y la cultura visual han llevado, más recientemente, a definir nuevas perspectivas de interpretación.

Estas nuevas miradas se vinculan estrechamente con las reflexiones que se han venido realizando acerca de la cultura visual y la intensificación de la “tendencia moderna a plasmar en imágenes o visualizar la experiencia” que caracteriza a la cultura actual (Mirzoeff, 2003; 23).

Así, por ejemplo, Crouch y Lübbren (2003) abordando la relación turismo/cultura visual proponen centrarse no sólo en objetos visuales ‑tales como fotografías, folletos turísticos, postales‑ sino también en todas las relaciones que se establecen entre objetos, prácticas, expectativas, experiencias, ideologías, etc. entendidos como elementos que constituyen una red más amplia (Crouch y Lübbren, 2003). En su propuesta, además, relativizan la primacía que históricamente se le atribuyó al sentido de la vista en relación con el turismo señalando la necesidad de analizar la dimensión visual de la experiencia turística junto con otras dimensiones sensoriales.

Tradicionalmente al abordar la relación que se establece en los procesos de producción y consumo (de imágenes, entre otras cosas) vinculados a la práctica turística se empleó un esquema polarizado en el que se asumía que la producción de imágenes e ideas acerca de objetos y lugares de interés turístico eran generadas por aquellos actores interesados en el desarrollo del turismo (empresarios, organismos públicos), mientras que para el turista se reservaba el consumo de estas imágenes e ideas propuestas (Crouch, 2004; Scarles y Lester, 2013). Actualmente, y recuperando desarrollos conceptuales vinculados a la discusión de la relación estructura/agencia (véase MacCannell, 2001) se considera que los turistas también son actores activos en la producción de imágenes (Crang, 1997). La revisión de las divisiones tajantes o dicotómicas entre las esferas de la producción y el consumo en el turismo lleva a relativizar la influencia que ciertas imágenes e ideas intencionadas pueden ejercer en el turista sin que ello implique desconocer la importancia de aspectos esenciales para comprender el turismo (entre ellos, el rol de actores vinculados a la construcción deliberada de ciertas representaciones; Crouch, 2004).

Asimismo, a la luz de nuevos desarrollos conceptuales que, asumiendo que la sociedad actual es una sociedad móvil, ensayan nuevas formas de comprender diferentes objetos visuales, entre ellos las postales. En esta línea se incluyen trabajos que intentan colocar bajo análisis otros aspectos de la postal además de la imagen y el texto. Ejemplo de esto lo constituye el trabajo de Andriotis y Mavri (2013) quienes utilizan el New Mobilities Paradigm propuesto por John Urry para analizar la postal bajo cinco formas interrelacionadas de movilidad: la movilidad corporal, la movilidad imaginativa, la movilidad comunicativa, la movilidad virtual y la movilidad de los objetos. Su intención es abordar la postal no solo como una forma de presentar lugares sino también como un objeto de indagación que representa, conlleva y habilita estas formas de movilidad interdependientes y todos los sistemas involucrados en ellas.

El presente artículo puede haber sido publicado parcial o totalmente en algunos de mis blogs.

This article may have been published in part or in full on one of my blogs.

Mis Blogs y Sitios Web / My Blogs & Websites:

- La Cucina di Susana.

- Cucinando con Susana

- El Mundo de los Postres

- Crónicas de Un Mundo en Conflicto.

Telegram and Whatsapp

Thanks!