Béla Guttmann , sacked by Benfica after winning two European Cups in the 60s, made a legendary statement: "Without me, they will never win again."

Since then, they have lost seven finals in continental competitions. Even after the death of the mysterious Budapest-born coach, the conspiracy is still alive.

It is the last cross of the most important game of the season and of the last two decades for Benfica.

The Eagles can end the curse and win a European title more than half a century after that last conquest in the days of Eusebio. They were losing, Tacuara Cardozo equalised and then the feeling that everything was possible.

But there are still those few seconds left to reach extra time against Chelsea. That corner from the right is also missing. Third minute of added time, at the Amsterdam Arena. The ball rains down on the area like a curse and defender Branislav Ivanovic appears, alone and perfectly positioned.

The Serbian heads it high, the ball goes in and becomes that 2-1 that will last until the English team is crowned. Benfica, for the seventh consecutive European final, is left empty of glory. Everyone looks towards the same corner of history. And they point to the same name: Béla Guttmann, the coach who opened the doors to double European Cup consecration (in 1961 and 1962) and who then marked the beginning of a succession of pains for the Portuguese giant.

The huge screen in the Amsterdam stadium shows the crying of a boy who is entering his adolescence. He is dressed in red, as the occasion calls for. His father covers him, but the consolation is not enough. He continues crying. On the day of his birth, Béla Guttmann had already died. But the boy without consolation is beginning to understand what it is all about.

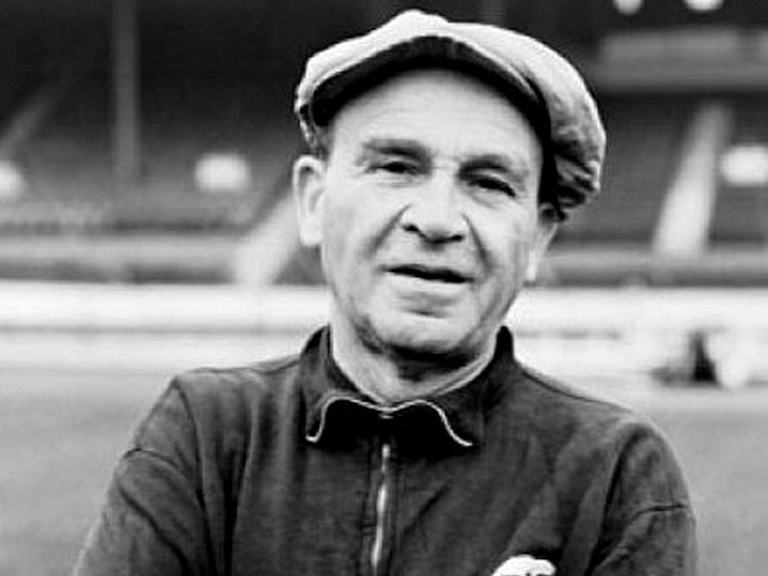

The legendary coach, born in Budapest during the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the most successful of Benfica's successful life, died in 1981. He was 81 years old, had several titles and a thousand mysteries at the time of his burial. He had said a phrase that history reinterpreted as a curse: "Without me, Benfica will never win in Europe again." It happened after his first departure from the Lisbon club, in 1962. He returned soon after. But the idyll was no longer such. In the 65/66 season - the season of his return - he was unable to continue the glorious path of that team that was marking an era, almost like Barcelona in recent days. That campaign, Sporting - the city's archrival - won the League; Braga won the Portuguese Cup. And in the Champions League, Manchester United eliminated Benfica with a historic thrashing: 5-1 away for an aggregate of 8-3 in the series. Béla was also a prisoner of his own curse.

Since the happy days of Guttmann, nothing has been the same for Benfica. As if a ghost were haunting them at the big events, they have not stopped losing finals. Much of it resembled and still resembles a convention accepted by all. This note was even born from the assumption that Benfica would lose. It was proposed ten minutes before the end of the match against Chelsea, with the 1-1 heading into extra time. It was accepted. And now it is happening. Before the recent outcome, there were other decisive matches with defeat, even in the magical 60s: in 1963, against Nereo Rocco's Milan; in 1964, against Helenio Herrera's implacable Inter; in 1968, against Matt Busby's Manchester United. Without Eusebio, there were other finals and other setbacks. Two in the current Champions League (in 1988 against PSV Eindhoven on penalties; and in 1990 against Arrigo Sacchi's Milan) and two in the current Europa League (in 1983 against Anderlecht and now, in this re-establishment of the old stigma). All the finals had a similar feature: favourable luck was arbitrarily absent. And to make matters worse, Porto's neighbours won seven international titles in that same journey; and even Sporting lifted the Cup Winners' Cup in 1964. Béla was a paradigm of the globetrotting coach. A passionate man capable of travelling the most inhospitable roads in the name of embracing his profession as a coach. He also turned out to be the owner of a peculiarity that condemned the best of his teams and himself. That epic final against Real Madrid in 1962 now seems like a well-told lie. But it happened. And since then and since his statement, nothing was the same for Las Aguilas or for him. Benfica never won in Europe again and Guttmann never won again in any of his subsequent campaigns. The coach who had spent a short time in Quilmes in 1953 had managed Peñarol in Uruguay, the Austrian national team, Servette in Switzerland, Panathinaikos in Greece, Austria Vienna and Porto in that same Portugal, which never forgot him for various reasons.

But beyond the myths and beliefs there is also another truth that has to do with the game. And above all with a star who marked an era: the immense Eusebio, who was the best that Benfica showed to the world. He, dressed in red, became a universal star and a source of pride. And now also a source of gratitude. The paper, handwritten by an anonymous person, was displayed on the statue of Eusebio until it was taken away by time or the wind or both.

There, at the entrance to the Da Luz stadium in Lisbon, was a single word in large black letters on a white background: "Obrigado" (thank you). It didn't matter who had written it; it was a message from all those who saw him play. In the tribute forever, the best footballer in Portugal and Benfica appears kicking a ball. Some say that it was based on a scene from the 1966 World Cup, when La Pantera was the most outstanding player and the top scorer. Others say it was the fifth goal against Real Madrid in the 5-3 win in the European Cup final, at the Olympic Stadium in Amsterdam, in 1962. In any case, these are moments that define him as what he was: a legend.

In addition to the gratitude of the people, Eusebio is also defined by numbers and laurels. The International Federation of Football History and Statistics places him among the top players of the 20th century; he scored more than 500 goals, with an average of 0.88 per game; In Europe he won the Ballon d'Or and the Golden Boot twice; with Benfica, he won two Champions Cups, eleven Leagues and five Portuguese Cups. He was everything that one of his nicknames said: The Pearl of Mozambique. "Without Eusebio it is more difficult," say the fans of Las Aguilas to explain this half century of frustrations in Europe. In the first eight years of Eusebio at Benfica, the Lisbon club reached five Champions Cup finals. In the rest of its history, only two.

The writer Eduardo Galeano only needed a handful of phrases to define him: "He was born destined to shine shoes, sell peanuts or steal from the distracted. As a child, they called him Ninguém, nobody, none. The son of a widowed mother, he played football with his many brothers in the sandbanks of the suburbs, from dawn to dusk. In the 1966 World Cup, his strides left a trail of opponents on the ground and his goals, from impossible angles, unleashed endless applause. An African from Mozambique was the best player in the entire history of Portugal. Eusebio: tall legs, drooping arms, sad look." But Eusebio, who seemed like a magician and unbreakable, also suffered from that devastating message from Béla Guttmann.

That boy who was displayed on the huge screen, his father, everyone around him and even Eusebio himself cannot believe it. Not even those who are Catholics and imagined that a coach called Jorge Jesus was the one predestined to rescue them. All of them, in some way, are burdened by that arduous and uncomfortable history. They know it even if they do not admit it or do not want to admit it. Even if it hurts them in the depths of their hearts as fans: Benfica is the Club of the Curse. Or at least that is what it seems.

Béla Guttmann, echado por el Benfica tras ganar dos Copas de Europa en los 60, lanzó una mítica frase: "Sin mí, no volverán a ganar".

Desde entonces, perdió siete finales de competiciones continentales. Aún muerto el misterioso DT nacido en Budapest, la conjura sigue viva.

Es el último centro del partido más importante de la temporada y de las últimas dos décadas para el Benfica.

Las Aguilas pueden terminar con el maleficio y ganar un título europeo más de medio siglo después de aquella última conquista en los días de Eusebio. Iban perdiendo, llegó el empate de Tacuara Cardozo y luego la sensación de que todo era posible.

Pero queda ese puñado de segundos para llegar al alargue ante Chelsea. También falta ese corner desde la derecha. Tercer minuto de descuento, en el Amsterdam Arena. La pelota llueve en el área como una maldición y aparece, solo y perfectamente ubicado, el defensor Branislav Ivanovic.

Cabecea bombeado el serbio, la pelota ingresa y se transforma en ese 2-1 que durará hasta la consagración del equipo inglés. Benfica, por séptima final europea consecutiva, se queda vacío de gloria. Todos miran hacia el mismo rincón de la historia. Y le apuntan al mismo nombre: Béla Guttmann, aquel entrenador que abrió las puertas de la doble consagración en la Copa de Europa (en 1961 y 1962) y que luego marcó el principio de una sucesión de dolores para el gigante portugués.

La pantalla enorme del estadio de Amsterdam muestra el llanto de un chico que camina su adolescencia. Está vestido de rojo, como la ocasión invita. El padre lo cobija, pero el consuelo no alcanza. Sigue llorando. El día de su nacimiento, Béla Guttmann ya había fallecido. Pero el chico sin consuelo está comenzando a comprender de qué se trata todo aquello.

El mítico entrenador, nacido en Budapest en tiempos del Imperio Austro-Húngaro, el más exitoso de la exitosa vida del Benfica, murió en 1981. Tenía 81 años, varios títulos y mil misterios al momento de su entierro. El había dicho una frase que la historia resignificó como una maldición: "Sin mí, el Benfica no volverá a ganar en Europa". Sucedió luego de su primera salida del club de Lisboa, en 1962. Regresó pronto. Pero el idlio ya no era tal. En la temporada 65/66 -la de su retorno- no pudo darle continuidad al camino glorioso de ese equipo que estaba marcando una época, casi como el Barcelona de los días recientes. Esa campaña, el Sporting -archirrival de la ciudad- se llevó la Liga; el Braga obtuvo la Copa de Portugal. Y en la Copa de Campeones, el Manchester United lo eliminó al Benfica con una goleada histórica: un 5-1 a domicilio para un global de 8-3 en la serie. Béla también estaba preso de su propia maldición.

Desde los días felices de Guttmann nada resultó igual para el Benfica. Como si un fantasma lo abordara en las grandes citas, no paró de perder finales. Mucho se pareció y se parece a una convención aceptada por todos. Esta nota -incluso- nació de la presunción de que el Benfica perdería. Fue propuesta diez minutos antes del desenlace del partido ante Chelsea, con el 1-1 encaminado al alargue. Fue aceptada. Y ahora sucede. Antes del desenlace reciente, hubo otros encuentros decisivos con derrota, incluso en los mágicos 60: en 1963, frente al Milan de Nereo Rocco; en 1964, contra el implacable Inter de Helenio Herrera; en 1968, frente al Manchester United de Matt Busby. Ya sin Eusebio llegaron otras finales y otros tropiezos.

Dos por la actual Champions (en 1988 ante el PSV Eindhoven por penales; y en 1990 frente al Milan de Arrigo Sacchi) y dos por la actual Europa League (en 1983 contra el Anderlecht y ahora, en esta refundación del viejo estigma). Todos las finales tuvieron un rasgo afín: el azar favorable se ausentó antojadizamente. Y para colmo de males, los vecinos del Porto ganaron siete títulos internacionales en ese mismo recorrido; y hasta el Sporting alzó la Recopa en 1964.

Béla fue un paradigma del entrenador trotamundos. Un apasionado capaz de recorrer los caminos más inhóspitos en nombre de abrazar su profesión de técnico. También resultó el dueño de una particularidad que condenó al mejor de sus equipos y a él mismo. Aquella final épica ante el Real Madrid en 1962 parece ahora una mentira bien contada.

Pero aconteció. Y desde entonces y desde su frase ya nada fue igual para Las Aguilas ni para él. Benfica jamás volvió a ganar en Europa y nunca Guttmann volvió a vencer en ninguna de sus escalas posteriores. Aquel técnico que en 1953 había pasado un rato breve por Quilmes dirigió desde aquella conquista memorable a Peñarol de Uruguay, al seleccionado de Austria, al Servette de Suiza, al Panathinaikos del Grecia, al Austria Viena y al Porto de ese mismo Portugal que nunca lo olvidó por razones diversas.

Pero más allá de los mitos y de las creencias también existe otra verdad que tiene que ver con el juego. Y sobre todo con un crack que marcó una época: el inmenso Eusebio, que fue lo mejor que el Benfica le mostró al mundo. El, vestido de rojo, se transformó en estrella universal y en orgullo. Y ahora también en gratitud. El papel, escrito a mano por un anónimo, lució en la estatua a Eusebio hasta que se lo llevó el tiempo o el viento o las dos cosas.

Allí, en los accesos del estadio Da Luz, de Lisboa, decía una sola palabra grande en letras negras sobre fondo blanco: "Obrigado" (gracias). No importaba quién la había escrito; era un mensaje de todos los que lo vieron jugar. En el tributo para siempre, el mejor futbolista de Portugal y del Benfica aparece pateando una pelota. Algunos cuentan que se basaron en una escena del Mundial de 1966, cuando La Pantera fue el más destacado de los futbolistas y el máximo anotador. Otros señalan que es el quinto gol al Real Madrid en el 5-3 de la final de la Copa de Europa, en el Olímpico de Amsterdam, en 1962. En cualquier caso, momentos que lo definen como lo que fue: una leyenda.

Además de la gratitud de la gente, a Eusebio también lo definen los números y los laureles. La Federación Internacional de Historia y Estadísticas del Fútbol lo ubica en el top de los mejores jugadores del Siglo XX; convirtió más de 500 goles, con un promedio de 0,88 por encuentro; en Europa ganó el Balón de Oro y el Botín de Oro en dos ocasiones; con Benfica, obtuvo las dos Copas de Campeones, once Ligas y cinco Copas de Portugal. Era todo lo que uno de sus apodos contaba: La Perla de Mozambique. "Sin Eusebio es más difícil", dicen a modo de explicación los hinchas de Las Aguilas para explicar este medio siglo de frustraciones en Europa. En los primeros ocho años de Eusebio en Benfica, el club lisboeta accedió a cinco finales de la Copa de Campeones. En el resto de su historia, a sólo dos.

Al escritor Eduardo Galeano le alcanzaron un puñado de frases para definirlo: "Nació destinado a lustrar zapatos, vender maníes o robar a los distraídos. De niño, lo llamaban Ninguém, nadie, ninguno. Hijo de madre viuda, jugaba al fútbol con sus muchos hermanos en los arenales de los suburbios, desde el amanecer hasta la noche. En el Mundial del 66, sus zancadas dejaron un tendal de adversarios por el suelo y sus goles, desde ángulos imposibles, desataron ovaciones de nunca acabar. Fue un africano de Mozambique el mejor jugador de toda la historia de Portugal. Eusebio: altas piernas, brazos caídos, mirada triste". Pero también Eusebio, que parecía mago e irrompible, padeció aquel mensaje devastador de Béla Guttmann.

Aquel chico que se exhibía en la pantalla enorme, su padre, todos los que a su alrededor estaban y hasta el mismísimo Eusebio no lo pueden creer. Ni los que son católicos e imaginaban que un entrenador llamado Jorge Jesús era el predestinado para rescatarlos. A todos ellos, de algún modo, les pesa esa historia ardua e incómoda. Lo saben aunque no lo admitan o no lo quieran admitir. Incluso aunque les duela en lo más profundo de sus corazones de hinchas: el Benfica es el Club de la Maldición. O al menos eso parece.

Source images / Fuente imágenes.

Gracias por leer. / Thank you for reading.

Los enlaces de mis sitios web / Links to my websites :

Upvoted. Thank You for sending some of your rewards to @null. Get more BLURT:

@ mariuszkarowski/how-to-get-automatic-upvote-from-my-accounts@ blurtbooster/blurt-booster-introduction-rules-and-guidelines-1699999662965@ nalexadre/blurt-nexus-creating-an-affiliate-account-1700008765859@ kryptodenno - win BLURT POWER delegationNote: This bot will not vote on AI-generated content

Telegram and Whatsapp