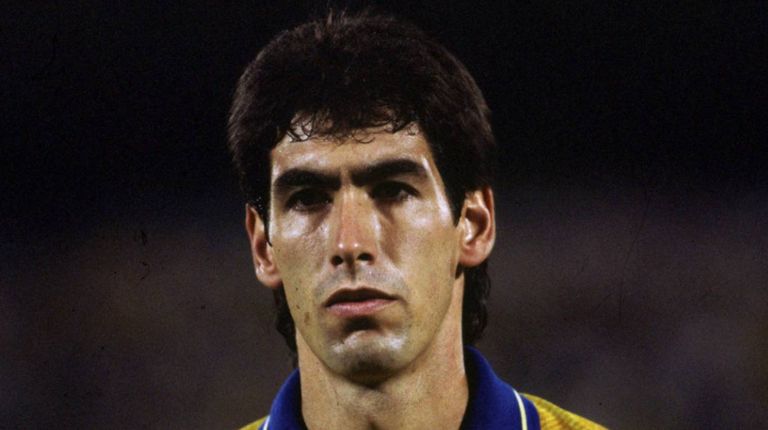

Andrés Escobar was one of the greatest central defenders in the history of Colombian football. He scored a goal against the United States in the 1994 World Cup. A few days later he was murdered in Medellín. He was 27 years old.

The image takes place in Villa Crespo, in a large bar, equipped for concerts. In the center, on top of the stage, a group called Viejo Fumando invites the people below to sing in chorus, who, below, applaud and join in: “And you have to leave/whatever is playing in the background.” It is the chorus of a tribute that astonishes: the song is inspired by Andrés Escobar, the Colombian soccer player who was murdered at the age of 27, a few days after scoring an own goal in the 1994 World Cup, against the host United States.

The song continues under the Buenos Aires sky: "Governments of the grave, bodies of the grave / threats to 'Barrabás' / It's that if he plays, his family dies / a clear mafia message / the goal against after the bad debut / condemns them to return home / with the shame of being the first, / "You have to show your face, / when they come to see me. The second surprise occurs: almost everyone present at the recital knows who he is. A certainty: Escobar is a memory that beats, and that can also be heard.

Andrés Escobar Saldarriaga played football better than very well. His nickname said who he was: El Caballero (The Gentleman). He was part of a generation of footballers (such as Carlos Valderrama, René Higuita or Leonel Alvarez) who changed the mentality of this sport in their country. Escobar was a tall central defender (he was 184 centimetres tall), precise, with a good aerial game, but above all a sympathetic and militant player with his head up and the ball on the ground. He played for Atlético Nacional in the late 80s and early 90s, perhaps the best Colombian team in history. At that time they were champions of the League, the Libertadores and the Interamericana. In the intercontinental final of 1989, Arrigo Sacchi's imposing Milan took until the last gasp of extra time to beat them.

He had stood out in the 1990 World Cup, which had Colombia as one of the revelations. He wore the number two on his back in those days when El Equipo Cafetero was becoming an attraction: to advance to the round of 16, they played against Germany -finalist in Mexico 1986 and later champion in Italy- and tied them in an epic finale. Then came Higuita's mistake against Cameroon and the farewell in the round of 16. What followed that elimination was the best of Colombian football: with a match that deserved applause, they rose as a candidate for many after beating Argentina (5-0 at the Monumental, in the Qualifiers). The subsequent one, already in the 1994 World Cup, was a succession of blows. Two defeats, early elimination and, again, tragedy.

The journalist Daniel Coronell wrote in the Colombian magazine Semana: “Andrés Escobar was 27 years old when he was killed. In the early hours of that Saturday, July 2, 1994, Humberto Muñoz Castro left the barrel of a .38-caliber rifle vacant on the footballer’s back. It happened in the parking lot of a discotheque in Medellín where Andrés had gone to talk with some friends and try to forget the own goal he had scored ten days earlier in the World Cup in the United States.” The killer shot him twelve times. And after each shot he shouted his fierce irony, that cruelty: “Great goal.”

Some time earlier, Escobar had had an altercation with brothers Pedro and Santiago Gallón Henao - Muñoz Castro's bosses, both suspected of links to drug trafficking and paramilitaries - over that target. They treated him badly while El Caballero del Fútbol tried to explain to them that it was basically a game and that it had been a mistake. They didn't understand. Escobar left the place. They followed him. A couple of minutes later, in the parking lot, only the gunshots of the crime could be heard.

Ricardo Silva Romero, film critic and columnist for the newspaper El Tiempo, wrote a novel in 2009 entitled "Autogol" in which he portrays those days in 1994. In an interview, as a presentation of his book, he was asked: "Do you think that we Colombians have forgotten Andrés Escobar?" His brief response sounded very much like an invitation to reflection: "I think that the day we truly remember him, the day that what happened to him no longer shakes us, we will have something more of a nation."

Andrés Escobar fue uno de los grandes marcadores centrales de la historia del fútbol colombiano. En el Mundial de 1994 marcó un gol contra Estados Unidos. A los pocos días fue asesinado en Medellín. Tenía 27 años.

La imagen tiene lugar en Villa Crespo, en un amplio bar, acondicionado para recitales. En el centro, en lo alto del escenario, un grupo llamado Viejo Fumando invita a cantar a coro a la gente de abajo, quienes, abajo, aplauden y se suman: “Y tienes que salir/lo que sea que suena de fondo”. Es el estribillo de un homenaje que asombra: la canción está inspirada en Andrés Escobar, el futbolista colombiano que fue asesinado a los 27 años, pocos días después de marcar un gol en contra en el Mundial de 1994, contra el local de Estados Unidos.

La canción sigue bajo el cielo de Buenos Aires: "Gobiernos de tumba, cuerpos de tumba / amenazas al 'Barrabás' / Es que si juega, su familia muere / un claro mensaje mafioso / el gol en contra tras el mal debut / los condena a volver a su casa / con la vergüenza de ser el primero, / "Tienes que dar la cara, / cuando vengan a verme. Se produce el segundo asombro: casi todos los presentes en el recital saben quién es. Una certeza: Escobar es un recuerdo que late, y que también se escucha.

Andrés Escobar Saldarriaga jugaba al fútbol mejor que muy bien. El apodo decía quién era: El Caballero. Formó parte de una generación de futbolistas (como Carlos Valderrama, René Higuita o Leonel Alvarez) que cambiaron la mentalidad de este deporte en su país. Escobar era un marcador central, alto (medía 184 centímetros), preciso, con un buen juego aéreo, pero sobre todo simpatizante y militante de la cabeza levantada y el balón contra el suelo. Participó en el Atlético Nacional a finales de los 80 y principios de los 90, quizás el mejor equipo colombiano de la historia. En ese momento fue campeón de la Liga, la Libertadores y la Interamericana. En la final intercontinental de 1989, el imponente Milán de Arrigo Sacchi tardó hasta el último suspiro de la prórroga en vencerlo.

Había destacado en aquel Mundial de 1990 que tuvo a Colombia como una de las revelaciones. Llevaba el número dos a la espalda en aquellos días en que El Equipo Cafetero se convertía en un atractivo: para pasar a octavos jugaba contra Alemania -finalista en México 1986 y luego campeón en Italia- y lo empataba en un final épico. Luego vino el error de Higuita ante Camerún y el adiós en octavos. Lo que siguió a esa eliminación fue lo mejor del fútbol colombiano: con un partido que mereció aplausos, se alzó como candidato para muchos tras vencer a Argentina (5-0 en el Monumental, por las Eliminatorias). La posterior, ya en el Mundial de 1994, fue una sucesión de golpes. Dos derrotas, eliminación anticipada y, de vuelta, tragedia.

El periodista Daniel Coronell lo escribió en la revista colombiana Semana: “Andrés Escobar tenía 27 años cuando lo mataron. En la madrugada de aquel sábado 2 de julio de 1994, Humberto Muñoz Castro dejó vacante el tambor de un calibre 38 largo en el espalda del futbolista. Ocurrió en el estacionamiento de una discoteca de Medellín donde Andrés había ido a conversar con unos amigos y tratar de olvidar el gol en propia puerta que había marcado diez días antes en el Mundial de Estados Unidos". El asesino le disparó doce veces. Y tras cada disparo gritaba su feroz ironía, esa crueldad: "Golazo".

Tiempo antes, Escobar había tenido un altercado con los hermanos Pedro y Santiago Gallón Henao -patrones de Muñoz Castro, ambos sospechosos de vínculos con el narcotráfico y paramilitares- por ese objetivo. Lo trataron mal mientras El Caballero del Fútbol intentaba explicarles que en el fondo era un juego y que había sido un error. No lo entendieron. Escobar abandonó el lugar. Ellos lo siguieron. Un par de minutos después, en el estacionamiento, solo se escuchaban los disparos del crimen.

Ricardo Silva Romero, crítico de cine y columnista del diario El Tiempo, escribió en 2009 una novela titulada "Autogol" en la que retrata aquellos días de 1994. En una entrevista, a modo de presentación de su libro, le preguntaron: "Haz ¿usted cree que los colombianos nos hemos olvidado de Andrés Escobar?" Su breve respuesta sonó mucho a una invitación a la reflexión: “Creo que el día que lo recordemos de verdad, el día que lo que le pasó no deje de sacudirnos, tendremos algo más de nación”.

Source images / Fuente imagenes.

Gracias por leer. / Thank you for reading.

Los enlaces de mis sitios web / Links to my websites :