The internet has long been heralded for its ability to connect people, facilitate the sharing of ideas, and expand users’ horizons and with good reason.

Search boxes put the world’s knowledge at our fingertips. From email to instant messaging to video calls, we’ve developed progressively more lifelike modes of communicating with each other.

Yet, it’s become increasingly apparent that something has gone awry in the way we’ve built online spaces. Anyone who’s jerked their eyes from their phones, feeling angry or frightened, after an hour of scrolling a social media newsfeed has fallen into a kind of trap.

The social media problem

The machinery feeding us these experiences sows discord at least as often as it connects us to other people or other ideas that enrich our lives. We have to ask why.

The simple answer is that the algorithms feeding us post after post aren’t designed with our best interests in mind. Rather, their purpose is to generate profits for the companies that built them. Inflammatory content drives clicks and outraged reactions that attract others’ attention.

This engagement is closely monitored to develop advertising profiles on users. Which social media and other companies can turn into revenue. The businesses grow while we’re trapped into echo chambers of content that draws our attention in the worst ways. It’s a vicious cycle.

So it was particularly ironic when I listened to Mark Zuckerberg talking with Casey Newton the other day about how he wants Facebook to lead the charge in building out the next phase of the internet, the “metaverse.”

The history of the metaverse

It’s a concept that first appeared in William Gibson’s 1982 short story entitled “Burning Chrome” under the term “cyberspace.”

It also came up in his 1994 novel Neuromancer, which depicted the transportation of the human mind into virtual reality.

However, it was Neal Stephenson’s novel “Snow Crash,” published in 1992, that defined many of the concepts we now associate with the term metaverse.

In Stephenson’s imagined reality, large and powerful conglomerates control the world, and society is highly unequal. The metaverse is a place where citizens escape the harsh realities of life.

The term “metaverse” is itself a portmanteau of “meta,” which means “beyond” and “universe.” The concept is generally understood as a shared space in the virtual world that incorporates enhanced physical elements. A sort of future internet in which virtual 3D spaces continuously exist in connection with each other.

One definition describes the metaverse as “the sum of all virtual worlds.” Imagine, for example, if the gaming universes of multiplayer online games (MMOGs) like World of Warcraft, Runescape, and Second Life were connected, complete with their own currencies and economies.

This collective virtual space could permanently exist parallel to and independent of the actual physical world. In this space, people could continuously interact with one another in real-time. That’s the metaverse.

With VR and AR technology becoming increasingly widespread, now is the time for us to be thoughtfully approaching how we build this virtual extension of our world.

Our current tech ecosystem should be critically studied so that we avoid the mistakes of the past. We should look to all available technologies and business models to come up with ways to implement this phase of the internet. We need to make it better than its predecessor.

Surrounded by walled gardens

The current internet is premised on a foundation of centralized infrastructure. It is a series of “walled gardens,” where siloed platforms, Facebook, Amazon, Google, host information on centrally-owned private servers. This information they permit people to use as long as they adhere to the platforms’ terms.

This structure provides a level of convenience unthinkable only a couple of decades ago. Packages ordered and delivered on the same day; gigabyte upon gigabyte of cloud email storage. But the tradeoff is also crucial.

In this virtual world, individuals must accept that they are renters, not owners. When they cancel their subscription or misplace their sign-in credentials, they lose access to the digital items they think of as “theirs.”

Entrusting the early development of the metaverse to these companies could prove disastrous. It’s all too easy to lose an hour reading tweets. Now, it’s rapidly become clear that flipping through videos on TikTok is all the more addictive. Just imagine what could come next with far more immersive metaverse experiences.

Implementation as a driving factor for good

The rise of the metaverse can be seen as amoral. Its ethical impacts are neither inherently good nor inherently bad. As is the case so often with new technology, the decisive factor is implementation.

Early portents of our metaverse have shown troubling tendencies. Tracking of users across sites and platforms, clandestine logging and sharing of sensitive information, and government surveillance have all found expression through the virtual world.

Moreover, today’s proto-metaverse is literally owned by monopolistic corporations. Anyone who has ever been locked out of their Gmail account understands this viscerally.

Our most important files, digital assets, memories, and thoughts are owned by the platforms that operate the services we used. They are simply licensed out to us, the users.

Many privacy experts have pointed out that no one truly “owns” their identity in today’s internet. Instead, we entrust it to centralized services such as social media applications, online banks, and more.

The highly publicized data breaches involving personal identity show that information stored digitally by centralized platforms is never truly safe.

The centralirt risk to the metaverse

The problem of platform dependence also threatens to exacerbate fragmentation and hamper interoperability in the metaverse.

At the start of his interview with Casey Newton, Zuckerberg laid out a vision that “no one company will run the metaverse — it will be an ’embodied internet’ operated by many different players in a decentralized way.”

However, later in the same interview when asked about how the metaverse will be governed he struck a different tune:

“[The metaverse] has to have the sense of interoperability and portability. You have your avatar and your digital goods, and you want to be able to teleport anywhere. You don’t want to just be stuck within one company’s staff. So for our part, for example, we’re building out the Quest headsets for VR, we’re working on AR headsets. But the software that we build, for people to work in or hang out in and build these different worlds, that’s going to go across anything. So if other companies build out VR or AR platforms, our software will be everywhere. Just like Facebook or Instagram is today.”

In other words, it’ll be walled gardens with lucrative licensing schemes for Facebook to continue to make money off of the user data that Facebook owns.

This is an unacceptable future. If this model of the internet is replicated in the metaverse, the physical world will begin to experience the same pressures as the digital world. Especially when it comes to identity, usage rights, and interoperability.

The totality of human experience could conceivably come into the control of a few powerful companies, and laws and customs emphasizing human rights like privacy could become little more than artifacts of a bygone era.

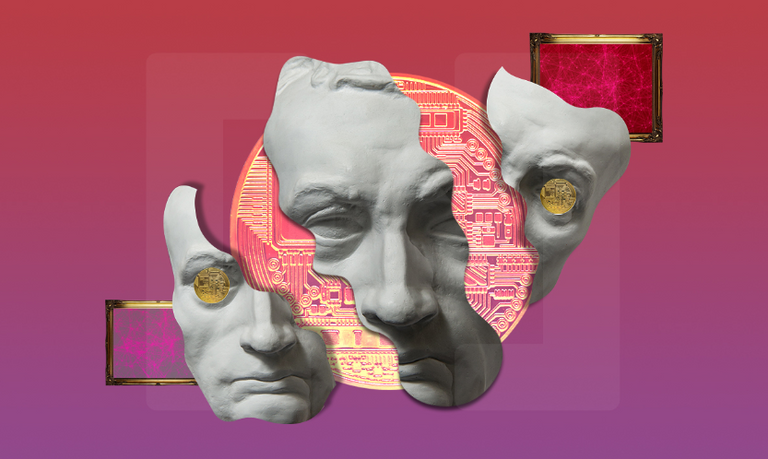

#Blockchain as a solution to metaverse centralization

However, it is not inevitable that the growing metaverse must cater to these practices. Blockchain offers another path.

The technology has grown exponentially over the past year. The number of people using it, and the number of projects building on decentralized networks like Ethereum, have continued to expand. The technology is making a mark on our proto-metaverse in some unexpected ways.

One of the world’s most prestigious auction houses, Sotheby’s, launched an exhibition this year in a premier location: the “NFT metaverse.” In this virtual space, Sotheby’s has created a digital replica of its London headquarters in the virtual streets of Decentraland — the first decentralized virtual world.

According to a report from June of 2021, “The virtual gallery will have five ground-floor spaces to show digital art, as well as a digital avatar of its London commissionaire Hans Lomulder to greet visitors at the door.”

The rise of NFTs shows exciting promise for the development of a better kind of metaverse. We’re able to own and control our digital property rather than entrust it to Big Tech corporations. We own it rather than have them allow us access only if we stay on their platforms, playing by their rules.

It’s up to us

The implications of the metaverse for individual privacy depend on what we collectively do now. A dystopian future in which Big Tech’s constant surveillance, platform dependence, and perverse economic incentives are ported into the physical world is possible but not inevitable.

If innovators and individuals work to incorporate new technologies like blockchain into emerging systems, we can build a dynamic, connected world where people can access goods, services, and information in ways never before thought possible. While also protecting and strengthening individual privacy autonomy and freedom.